Risks and Effects of Medicinal Plants as an Adjuvant Treatment in Mental Disorders during Pregnancy

Mental Health Obstetrics & Gynecology受け取った 26 Mar 2025 受け入れられた 15 Apr 2025 オンラインで公開された 16 Apr 2025

Focusing on Biology, Medicine and Engineering ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

END

Submit Article

受け取った 26 Mar 2025 受け入れられた 15 Apr 2025 オンラインで公開された 16 Apr 2025

Many medicinal plants used by patients with mental illnesses during pregnancy contain various active compounds. It is essential to guide and inform patients about the potential risks associated with the use of medicinal herbs, teas, plant parts, and plant-based products, as well as the critical time periods during which their use may be particularly harmful.

The aim of this article is to highlight the most commonly used medicinal plants with psychotropic effects and to emphasize the risks associated with their use in pregnant patients with mental disorders. Pregnant women worldwide frequently consume herbal medicines (including herbal teas, medicinal herbs, and plant extracts), under the mistaken belief that these substances are inherently safe for the fetus and entirely beneficial because of their natural origin, as opposed to synthetic alternatives. However, natural sedatives, hypnotics, and antidepressants—such as valerian, lemon balm, lavender, passionflower, St. John's wort, mint, and chamomile-can be used without supervision and often in combination with other sedative agents, further increasing the likelihood of unpredictable risks.

Methods: This study is a narrative review that involves the analysis and synthesis of scientific literature on the use of medicinal plants in mental health during pregnancy and lactation. The literature search was conducted using keywords, and data were collected from medical databases, including PubMed, Medscape, UpToDate, Elsevier, and Google Scholar.

Results and discussions: A significant concern is that patients may self-administer these substances without informing their healthcare provider. Medicinal plants can induce clinical, biochemical, and genomic alterations, modulate maternal immune responses, and interfere with enzymatic and cytochrome pathways, thereby affecting the concentration and pharmacokinetics of prescribed medications in maternal blood plasma. Moreover, the active compounds in herbal medicines can cross the placental barrier, posing potential risks to fetal development, including teratogenicity, toxicity, and delayed adverse effects.

CNS: Central Nervous System; CYP: Cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP3A4, CYP1A2); EMA: European Medicines Agency; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; GI: Gastrointestinal; GRAS: Generally Recognized As Safe; HMPs: Herbal Medicinal Products; HPA axis: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis; NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs; SNRIs: Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors; SSRIs: Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; TCAs: Tricyclic Antidepressants

Despite the potential therapeutic benefits of certain herbal remedies, concerns remain regarding their safety profile during pregnancy, particularly due to their pharmacokinetic variability and potential interactions with conventional psychotropic medications. The possible adverse effects of herbal medicinal products (HMPs) were classified by Michael A. Miller and David Vearrier (2021) into four distinct categories []:

Type "A" – Considered a more predictable category, these adverse effects are pharmacologically predictable, dose-dependent, and preventable through dose adjustment.

Type "B" – This category includes idiosyncratic and unpredictable reactions, independent of dose, with the potential for severe immunological and toxic consequences, including life-threatening complications.

Type "C" – Adverse effects resulting from chronic exposure to HMPs during prolonged therapy. These effects are well-documented, allowing for predictive risk assessment.

Type "D" – Refers to delayed adverse effects, such as carcinogenicity and teratogenicity. Some of these effects remain insufficiently studied, and data regarding their impact often emerge retrospectively, necessitating long-term epidemiological and statistical analysis. The authors further describe various adverse reactions associated with HMPs, including drug interactions, allergic responses, and toxic reactions, as well as the potential contamination of herbal products with heavy metals and other harmful substances []. A particular concern is the misidentification or substitution of plant species, which may result in exposure to toxic compounds. For instance, Mentha pulegium (pennyroyal) is sometimes confused with Mentha piperita (peppermint). However, Mentha pulegium contains a hepatotoxic compound that can induce centrilobular hepatocellular necrosis, which can lead to multisystem organ failure []. Additionally, this plant has been deliberately used as an abortifacient, raising concerns regarding its potential teratogenic and toxic effects during pregnancy. Herbal medicines are associated with a range of harmful effects, including nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, genotoxicity, mutagenicity, and teratogenicity [,]. However, it is important to acknowledge that HMPs may also exert beneficial pharmacological effects, which have been explored in therapeutic contexts to address anxiety, depressive symptoms, insomnia, and psychological distress. Within the field of mental health, HMPs are most commonly utilized for their anti-stress, antidepressant, anxiolytic, hypnotic, sedative, anticonvulsant, and neuroprotective properties [,]. The potential use of herbal remedies during pregnancy warrants particular attention due to insufficient data on their safety and efficacy. According to the American Pregnancy Association (2022), the following herbal remedies are considered suitable for use during pregnancy: peppermint leaf, lemon balm, german chamomile, stinging nettles, and alfalfa. Among these, lemon balm, peppermint, and chamomile are commonly used for their anxiolytic, antidepressant, and hypnotic properties. However, their use requires caution, as certain pharmacological effects may pose risks depending on the dosage and duration of administration. When comparing the potential risks associated with these herbal remedies, the American Pregnancy Association classifies four of these herbs as "likely safe," with the exception of german chamomile, for which there is "insufficient evidence" regarding its safety during pregnancy [].

A comprehensive search was conducted using evidence-based medical research platforms, including PubMed, Medscape, UpToDate, Elsevier, and Google Scholar. The primary sources reviewed were primarily from English-language scientific literature. A total of 37 major sources, including meta-analyses and clinical research studies, were analyzed to assess the pharmacological effects of herbal medicines on mental health during pregnancy and lactation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: Medicinal plants exhibit psychotropic effects that are relevant to managing anxiety. These effects also play a role in addressing depressive symptoms., insomnia, and psychological distress during pregnancy and lactation; Documented therapeutic indications and safe use during pregnancy and/or lactation; Classified as FDA Category A, B, or C according to FDA pregnancy risk classification []. The exclusion criteria were as follows: Contraindications for the use during pregnancy and lactation; Documented interactions with standard pharmacological treatments or other medicinal plants; Classification as FDA Category D or Category D according to Michael A. Miller and David Vearrier; Documented nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, genotoxicity, mutagenicity, and teratogenicity.

St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) in mental health use. St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) is widely utilized in general medical practice due to its multifaceted pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumor, and antiviral effects [,]. In the field of mental health, it is frequently used in the management of Anxiety and depression (including sleep disturbances), irritability, and phobic disorders, mild to moderate postpartum depression, reduction of withdrawal symptoms, and cognitive enhancement []. St. John's Wort contains a diverse array of active compounds responsible for its pharmacological effects [,]. These include polycyclic phenols, flavonoids and bi-flavones, proanthocyanidins, xanthones, phloroglucins, naphthodianthrones. All compounds exhibit stress-protective properties, inhibit proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β), and suppress the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), ultimately reducing cortisol levels through neuroendocrine regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [].

Neurotransmitter modulation and interaction risks: The mechanism of action of St. John's Wort closely resembles that of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), as it inhibits the reuptake of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, reduces the expression of beta-adrenergic receptors, increases the density of serotonin (5-HT2A and 5-HT1A) receptors []. Due to its serotonergic activity, combining St. John's Wort with serotonergic medications (e.g., SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, L-tryptophan, lithium) is contraindicated, as this may lead to the development of serotonin syndrome [,]. Additionally, the active compounds in St. John's Wort exhibit an affinity for γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors, potentially altering the pharmacokinetics of psychotropic medications metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP3A, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2E1) [].

Reduced effectiveness of psychotropic drugs: St. John's Wort induces CYP3A4, leading to reduced plasma concentrations of buspirone (anxiolytic), carbamazepine (mood stabilizer), benzodiazepines []. Induction of P-glycoprotein reduces the therapeutic efficacy of clozapine and paliperidone, potentially exacerbating psychiatric symptoms [,].

Increased serotonin concentrations: When combined with SSRIs, SNRIs, TCAs, lithium, or L-tryptophan, St. John's Wort may cause excessive serotonergic activity, increasing the risk of serotonin syndrome [,].

Metabolic induction of psychotropic agents: St. John's Wort induces CYP1A2 and CYP3A4, enzymes involved in the metabolism of five atypical antipsychotics, one typical antipsychotic, two tricyclic antidepressants (tcas), three hypnotic medications [,]. Additionally, it alters the metabolism of trazodone, donepezil, and fentanyl.

Reduced effectiveness of barbiturates: The induction of CYP enzymes by St. John's Wort decreases the pharmacological effects of barbiturates, potentially diminishing their sedative and hypnotic effects [].

Clinical implications and safety considerations: While St. John's Wort is widely used for its antidepressant and anxiolytic properties, its complex pharmacological interactions necessitate caution, particularly in pregnant individuals and those undergoing psychotropic treatment. The use of St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) may result in alterations in neurotransmitter levels, induction of metabolic enzymes (CYP450, P-glycoprotein), and modifications in drug bioavailability [,,].

Valerian (valeriana officinalis) and its effects on mental health: Valerian preparations have been utilized since antiquity for the management of insomnia, anxiety, depression, and stress-related conditions. Valerian exhibits multiple pharmacological properties, including anxiolytic, sedative, antidepressant, antispasmodic, muscle relaxant, anticonvulsant, and hypotensive effects [,]. According to Mischoulon D. (2002), more than 40 clinical trials have been conducted to evaluate the effects of valerian across various populations, including children, the elderly, and menopausal women, yet clinical data remain limited regarding its use in pregnant and lactating women []. The conclusions regarding the therapeutic efficacy of valerian preparations are conflicting: On the one hand, valerian has been reported to exhibit comparable effectiveness to benzodiazepines, with the advantage of fewer adverse effects. On the other hand, meta-analyses and systematic reviews have yielded limited support for its clinical effectiveness [].

Safety of valerian during pregnancy: There is no consensus regarding the safety of valerian use during pregnancy, with divergent classifications across different medical authorities: In Australia, valerian preparations are classified as Category "A", signifying approval for use during pregnancy. Conversely, according to Medscape, valerian should be avoided during pregnancy and lactation due to insufficient safety data []. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) similarly recommends that valerian should not be used during pregnancy and lactation due to the absence of well-controlled studies []. According to other sources, valerian is contraindicated in the first trimester but may be considered in the second and third trimesters and during breastfeeding only if the potential benefits outweigh the risks [].

Drug interactions and safety concerns: Valerian has been reported to interact with 65 different medications, including three major groups of psychotropic drugs: Benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, hypnotics []. Due to its sedative effects, valerian, when combined with other CNS depressants, may paradoxically induce increased anxiety []. Additionally, co-administration with sedative medications is not recommended, and alternative pharmacological strategies should be considered []. There have also been concerns regarding potential hepatotoxicity, particularly at high doses (300–1000 mg per dose). While lower doses of 100 mg, as sometimes used in obstetric practice, may exhibit a placebo effect, the risk of hepatotoxicity remains a subject of debate [,]. A genotoxic risk has been described in the literature, with reports indicating that high concentrations of valerian extract (40–60 µg/mL) may induce discrete DNA damage in vitro, as demonstrated in animal models [].

Chamomile (Matricaria recutita and Chamaemelum nobile) in pregnancy: Chamomile generally refers to two plant species: German chamomile (Matricaria recutita) and Roman chamomile (Chamaemelum nobile) []. Chamomile contains over 120 biologically active compounds and exhibits antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, antibacterial, antifungal, and antipyretic properties [].

Safety concerns regarding chamomile use during pregnancy: There are significant concerns regarding the safety of chamomile use during pregnancy, particularly due to its potential abortifacient effects. According to a 2023 report, Roman chamomile “is probably not safe when taken orally as a medicine during pregnancy, as it may cause miscarriage”. Therefore, it is strongly advised to avoid Chamaemelum nobile during pregnancy []. A study by Cuzzolin, et al. [] reported that 21.6% of women who regularly consumed chamomile during pregnancy had an increased risk of threatened miscarriage and preterm birth []. Additionally, two cases of congenital heart disease (possibly linked to Down syndrome) and kidney enlargement in newborns were tentatively associated with maternal chamomile consumption during pregnancy []. Chamomile use in the third trimester has been statistically associated with a higher rates of preterm birth (p < 0.002), reduced fetal growth (p < 0.05), lower birth weight (p < 0.002) [,]. Furthermore, Beata Sarecka-Hujar, et al. [] suggested that chamomile may exhibit estrogenic activity, potentially interfering with cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP3A4, leading to alterations in drug metabolism and hormonal regulation [].

Drug interactions and risks associated with chamomile use: Chamomile has been reported to interact with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including aspirin, as well as other herbal products such as ginkgo biloba, garlic, ginger, and ginseng, which increase antiplatelet activity and may enhance the risk of bleeding []. Additionally, chamomile contains coumarins that may potentiate anticoagulant effects of medications such as warfarin, further increasing bleeding risk. When combined with opioid analgesics, valerian, or kava, chamomile may cause severe central nervous system (CNS) depression, warranting caution in co-administration []. Chamomile has also been reported to interact with psychoactive medications, including diazepam, propranolol, and chlorpromazine, due to its effects on enzymatic pathways and cytochrome activity, potentially causing profound sedation [,].

Melissa officinalis (lemon balm) exhibits a range of pharmacological properties, including cholinesterase inhibition, which enhances acetylcholine synaptic activity in the brain, promote neurogenesis, neuroprotective, and anxiolytic properties, as well as sedative, antidepressant, antiphobic, hypnotic, antispasmodic effects [-]. The lemon-scented essential oil extracted from lemon balm is classified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as "Generally Recognized as Safe" (GRAS) when used as a food flavoring []. According to a randomized clinical trial it has been reported that lemon balm and lavender demonstrated antidepressant effects similar to those of fluoxetine while exhibiting fewer side effects []. Additionally, lemon balm has been proposed as an alternative to benzodiazepines for the treatment of anxiety and sleep disorders []. Regarding its safety during pregnancy, is suggested that lemon balm preparations should only be used when the potential benefits to the mother outweigh the potential risks to the fetus or infant. Limited scientific evidence is available to establish the safety of its use during pregnancy [].

Several studies have evaluated the efficacy of lavender as a treatment for anxiety and depression disorders. Existing evidence suggests anxiolytic effects of lavender in patients with various mental disorders. Various routes of lavender administration for anxiety have been used in studies, including inhalation, massage, massage combined with aromatherapy, and oral administration [].

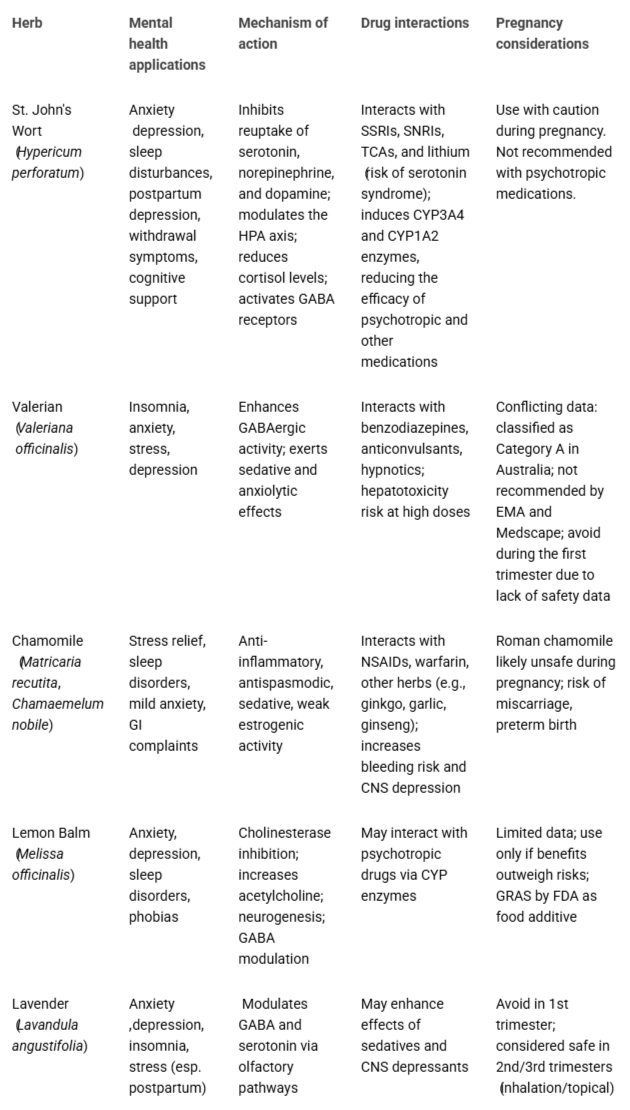

Fatemeh Effati-Daryani, et al. [] advise against the use of lavender during the first trimester of pregnancy due to a potential risk of spontaneous abortion, though lavender is generally considered safe during the second and third trimesters and might contribute to maternal relaxation and overall well-being []. A meta-analysis of three randomized controlled trials found that lavender preparations (aromatherapy, tea, cream) significantly improved sleep quality in postpartum mothers []. Topical and olfactory routes are the most commonly used in pregnant women; however, no evidence was found of one route being more effective than the other [] (Table 1).

The main limitation of this paper is the lack of robust scientific evidence confirming the safety and effectiveness of many medicinal plants during pregnancy. Several cited clinical trials lack confirmation of adherence to PRISMA guidelines, compromising scientific validity.

Additionally, due to the absence of reliable statistical data, we could not present quantitative analyses to support the conclusions. Limited data on potential adverse effects, herb-drug interactions, and regulatory oversight further challenge the safe use of medicinal plants during pregnancy. Limitations imposed on clinical research during pregnancy due to ethical constraints significantly impact on the study of this issue. As a result, clinical trials during pregnancy and lactation are generally not conducted.

Future research should focus on well-designed clinical trials that meet scientific standards, assessing safety, efficacy, and potential interactions. Enhanced regulatory oversight and quality control are essential to ensure consistent safety profiles

For many herbal medicinal products, data regarding their safety during pregnancy are insufficient, inconclusive, or conflicting, making it difficult to establish clear recommendations for their use.

It is well documented that many active compounds can cross the placental barrier, potentially influencing fetal development and posing risks related to teratogenicity, toxicity, and delayed adverse outcomes.

Many herbal medicines contain bioactive constituents capable of interacting with psychotropic medications, thereby altering their pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, dosage requirements, and overall therapeutic effects.

During pregnancy, physiological changes significantly alter drug metabolism and distribution, affecting both the mother and fetus. These changes must be taken into account when prescribing any pharmacological agents, particularly psychotropic medications, herbal medicines, or plant-based preparations.

Derrick Lung et all. Caustic Ingestions. Updated: Oct 19, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/813772-overview#a5

Bruno LO, Simoes RS, de Jesus Simoes M, Girão MJBC, Grundmann O. Pregnancy and herbal medicines: An unnecessary risk for women's health-A narrative review. Phytother Res. 2018 May;32(5):796-810. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6020. Epub 2018 Feb 8. PMID: 29417644.

Mills E, Dugoua J-J, Perri D, Koren G. Herbal medicines in pregnancy and lactation: An evidence-based approach. 1st ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2006.

McLay JS, Izzati N, Pallivalapila AR, Shetty A, Pande B, Rore C, Al Hail M, Stewart D. Pregnancy, prescription medicines and the potential risk of herb-drug interactions: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017 Dec 19;17(1):543. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-2052-1. PMID: 29258478; PMCID: PMC5738179.

Pregnancy nutrients you need to help your baby grow. https://www.babycenter.com/pregnancy/diet-and-fitness/pregnancy-nutrients-you-need-to-help-your-baby-grow_4540

Herbal Tea & Pregnancy. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/is-it-safe/herbal-tea/

Jessica C. Leek; Hasan Arif. Pregnancy Medications. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507858/

St John’s Wort (Herb/Suppl). https://reference.medscape.com/drug/amber-amber-touch-teal-st-johns-wort-344549#3

Zanoli P. Role of hyperforin in the pharmacological activities of St. John's Wort. CNS Drug Rev. 2004 Fall;10(3):203-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00022.x. PMID: 15492771; PMCID: PMC6741737.

Spiess D, Winker M, Chauveau A, Abegg VF, Potterat O, Hamburger M, Gründemann C, Simões-Wüst AP. Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Mental Diseases in Pregnancy: An In Vitro Safety Assessment. Planta Med. 2022 Oct;88(12):1036-1046. doi: 10.1055/a-1628-8132. Epub 2021 Oct 8. PMID: 34624906; PMCID: PMC9519192.

Di Carlo G, Nuzzo I, Capasso R, Sanges MR, Galdiero E, Capasso F, Carratelli CR. Modulation of apoptosis in mice treated with Echinacea and St. John's wort. Pharmacol Res. 2003 Sep;48(3):273-7. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00153-1. PMID: 12860446.

Butterweck V. Mechanism of action of St John's wort in depression : what is known? CNS Drugs. 2003;17(8):539-62. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317080-00001. PMID: 12775192.

Teufel-Mayer R, Gleitz J. Effects of long-term administration of hypericum extracts on the affinity and density of the central serotonergic 5-HT1 A and 5-HT2 A receptors. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1997 Sep;30 Suppl 2:113-6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979530. PMID: 9342771.

Windle ML. Fast Five Quiz: Herbal Supplements. https://reference.medscape.com/viewarticle/963972_4

Rombolà L, Scuteri D, Marilisa S, Watanabe C, Morrone LA, Bagetta G, Corasaniti MT. Pharmacokinetic Interactions between Herbal Medicines and Drugs: Their Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance. Life (Basel). 2020 Jul 4;10(7):106. doi: 10.3390/life10070106. PMID: 32635538; PMCID: PMC7400069.

Van Strater AC, Bogers JP. Interaction of St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) with clozapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012 Mar;27(2):121-4. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32834e8afd. PMID: 22113252.

Russo E, Scicchitano F, Whalley BJ, Mazzitello C, Ciriaco M, Esposito S, Patanè M, Upton R, Pugliese M, Chimirri S, Mammì M, Palleria C, De Sarro G. Hypericum perforatum: pharmacokinetic, mechanism of action, tolerability, and clinical drug-drug interactions. Phytother Res. 2014 May;28(5):643-55. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5050. Epub 2013 Jul 30. PMID: 23897801.

Balashov PP, Kolesnikova AM. [Possibilities of pharmacotherapy in treatment of anxiety disorders in pregnancy]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2013;113(7):60-4. Russian. PMID: 23994924.

David Mischoulon. The Herbal Anxiolytics Kava and Valerian for Anxiety and Insomnia. Psychiatric Annals. 2013;32(1):55-60. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020101-09

Valerian (Herb/Suppl). https://reference.medscape.com/drug/all-heal-amantilla-valerian-344550

European Union herbal monograph on Valeriana officinalis L., aetheroleum. EMA/HMPC/278053/2015 Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Published 2016. https://www.e-lactancia.org/media/papers/Valeriana-EMA2016_copia.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Mahmoudian A, Rajaei Z, Haghir H, Banihashemian S, Hami J. Effects of valerian consumption during pregnancy on cortical volume and the levels of zinc and copper in the brain tissue of mouse fetus. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2012 Apr;10(4):424-9. doi: 10.3736/jcim20120411. PMID: 22500716.

Naletov S. V. Clinical pharmacology of valerian preparations and European traditions of their use: the collapse of post-Soviet stereotypes. Review of foreign scientific sources. Ukrainian Medical Journal. https://umj.com.ua/uk/publikatsia-2757-klinicheskaya-farmakologiya-preparatov-valeriany-i-evropejskie-tradicii-ix-primeneniya-krushenie-postsovetskix-stereotipov-obzor-inostrannyx-nauchnyx-istochnikov

Chamomile use while Breastfeeding. https://www.drugs.com/breastfeeding/chamomile.html

Trabace L, Tucci P, Ciuffreda L. Natural relief of pregnancy-related symptoms and neonatal outcomes: above all do no harm. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;174:396-402.

Roman Chamomile. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/natural/752.html#Effectiveness

Cuzzolin L, Francini-Pesenti F, Verlato G, Joppi M, Baldelli P, Benoni G. Use of herbal products among 392 Italian pregnant women: focus on pregnancy outcome. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010 Nov;19(11):1151-8. doi: 10.1002/pds.2040. PMID: 20872924.

Sarecka-Hujar B, Szulc-Musioł B. Herbal Medicines-Are They Effective and Safe during Pregnancy? Pharmaceutics. 2022 Jan 12;14(1):171. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010171. PMID: 35057067; PMCID: PMC8802657.

Muñoz Balbontín Y, Stewart D, Shetty A, Fitton CA, McLay JS. Herbal Medicinal Product Use During Pregnancy and the Postnatal Period: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133(5):920-932. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003217. PMID: 30969204; PMCID: PMC6485309.

Abuhamdah S, Chazot PL. Lemon Balm and Lavender herbal essential oils: Old and new ways to treat emotional disorders? Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2008;19(4):221-226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cacc.2008.05.005

Mathews IM, Eastwood J, Lamport DJ, Cozannet RL, Fanca-Berthon P, Williams CM. Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability of Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis) in Psychological Well-Being: A Review. Nutrients. 2024 Oct 18;16(20):3545. doi: 10.3390/nu16203545. PMID: 39458539; PMCID: PMC11510126.

Araj-Khodaei M, Noorbala AA, Yarani R, Emadi F, Emaratkar E, Faghihzadeh S, Parsian Z, Alijaniha F, Kamalinejad M, Naseri M. A double-blind, randomized pilot study for comparison of Melissa officinalis L. and Lavandula angustifolia Mill. with Fluoxetine for the treatment of depression. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020 Jul 3;20(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-03003-5. PMID: 32620104; PMCID: PMC7333290.

Miraj S, Rafieian-Kopaei, Kiani S. Melissa officinalis L: A Review Study With an Antioxidant Prospective. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017 Jul;22(3):385-394. doi: 10.1177/2156587216663433. Epub 2016 Sep 11. PMID: 27620926; PMCID: PMC5871149.

Kennedy DA, Lupattelli A, Koren G, Nordeng H. Safety classification of herbal medicines used in pregnancy in a multinational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 Mar 15;16:102. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1079-z. PMID: 26980526; PMCID: PMC4793610.

Vidal-García E, Vallhonrat-Bueno M, Pla-Consuegra F, Orta-Ramírez A. Efficacy of Lavender Essential Oil in Reducing Stress, Insomnia, and Anxiety in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Dec 5;12(23):2456. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12232456. PMID: 39685078; PMCID: PMC11641599.

Effati-Daryani F, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M, Taghizadeh M, Mohammadi A. Effect of Lavender Cream with or without Foot-bath on Anxiety, Stress and Depression in Pregnancy: a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Caring Sci. 2015 Mar 1;4(1):63-73. doi: 10.5681/jcs.2015.007. PMID: 25821760; PMCID: PMC4363653.

Seiiedi-Biarag L, Mirghafourvand M. The effect of lavender on mothers sleep quality in the postpartum period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Complement Integr Med. 2022 Jan 24;20(3):513-520. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2021-0192. PMID: 35080353.

Larisa B, Larisa S, Jana C, Igor N. Risks and Effects of Medicinal Plants as an Adjuvant Treatment in Mental Disorders during Pregnancy. IgMin Res. April 16, 2025; 3(4): 195-200. IgMin ID: igmin298; DOI:10.61927/igmin298; Available at: igmin.link/p298

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

1Associate Professor, Department of Mental Health, Medical Psychology and Psychotherapy, State University of Medicine and Pharmacy Nicolae Testemitsanu, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

2Professor at the Department of Social Medicine and Management, State University of Medicine and Pharmacy Nicolae Testemitsanu, Chisinau, Republic of Moldova

Address Correspondence:

Spinei Larisa, Professor at the Department of Social Medicine and Management, State University of Medicine and Pharmacy, "Nicolae Testemitsanu", Chisinau, Republic of Moldova, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Larisa B, Larisa S, Jana C, Igor N. Risks and Effects of Medicinal Plants as an Adjuvant Treatment in Mental Disorders during Pregnancy. IgMin Res. April 16, 2025; 3(4): 195-200. IgMin ID: igmin298; DOI:10.61927/igmin298; Available at: igmin.link/p298

Copyright: © 2025 Larisa B, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Table 1: Herbal remedies in mental health during pregnancy:...

Table 1: Herbal remedies in mental health during pregnancy:...

Derrick Lung et all. Caustic Ingestions. Updated: Oct 19, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/813772-overview#a5

Bruno LO, Simoes RS, de Jesus Simoes M, Girão MJBC, Grundmann O. Pregnancy and herbal medicines: An unnecessary risk for women's health-A narrative review. Phytother Res. 2018 May;32(5):796-810. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6020. Epub 2018 Feb 8. PMID: 29417644.

Mills E, Dugoua J-J, Perri D, Koren G. Herbal medicines in pregnancy and lactation: An evidence-based approach. 1st ed. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press; 2006.

McLay JS, Izzati N, Pallivalapila AR, Shetty A, Pande B, Rore C, Al Hail M, Stewart D. Pregnancy, prescription medicines and the potential risk of herb-drug interactions: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017 Dec 19;17(1):543. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-2052-1. PMID: 29258478; PMCID: PMC5738179.

Pregnancy nutrients you need to help your baby grow. https://www.babycenter.com/pregnancy/diet-and-fitness/pregnancy-nutrients-you-need-to-help-your-baby-grow_4540

Herbal Tea & Pregnancy. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/is-it-safe/herbal-tea/

Jessica C. Leek; Hasan Arif. Pregnancy Medications. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507858/

St John’s Wort (Herb/Suppl). https://reference.medscape.com/drug/amber-amber-touch-teal-st-johns-wort-344549#3

Zanoli P. Role of hyperforin in the pharmacological activities of St. John's Wort. CNS Drug Rev. 2004 Fall;10(3):203-18. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00022.x. PMID: 15492771; PMCID: PMC6741737.

Spiess D, Winker M, Chauveau A, Abegg VF, Potterat O, Hamburger M, Gründemann C, Simões-Wüst AP. Medicinal Plants for the Treatment of Mental Diseases in Pregnancy: An In Vitro Safety Assessment. Planta Med. 2022 Oct;88(12):1036-1046. doi: 10.1055/a-1628-8132. Epub 2021 Oct 8. PMID: 34624906; PMCID: PMC9519192.

Di Carlo G, Nuzzo I, Capasso R, Sanges MR, Galdiero E, Capasso F, Carratelli CR. Modulation of apoptosis in mice treated with Echinacea and St. John's wort. Pharmacol Res. 2003 Sep;48(3):273-7. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00153-1. PMID: 12860446.

Butterweck V. Mechanism of action of St John's wort in depression : what is known? CNS Drugs. 2003;17(8):539-62. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200317080-00001. PMID: 12775192.

Teufel-Mayer R, Gleitz J. Effects of long-term administration of hypericum extracts on the affinity and density of the central serotonergic 5-HT1 A and 5-HT2 A receptors. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1997 Sep;30 Suppl 2:113-6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979530. PMID: 9342771.

Windle ML. Fast Five Quiz: Herbal Supplements. https://reference.medscape.com/viewarticle/963972_4

Rombolà L, Scuteri D, Marilisa S, Watanabe C, Morrone LA, Bagetta G, Corasaniti MT. Pharmacokinetic Interactions between Herbal Medicines and Drugs: Their Mechanisms and Clinical Relevance. Life (Basel). 2020 Jul 4;10(7):106. doi: 10.3390/life10070106. PMID: 32635538; PMCID: PMC7400069.

Van Strater AC, Bogers JP. Interaction of St John's wort (Hypericum perforatum) with clozapine. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012 Mar;27(2):121-4. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32834e8afd. PMID: 22113252.

Russo E, Scicchitano F, Whalley BJ, Mazzitello C, Ciriaco M, Esposito S, Patanè M, Upton R, Pugliese M, Chimirri S, Mammì M, Palleria C, De Sarro G. Hypericum perforatum: pharmacokinetic, mechanism of action, tolerability, and clinical drug-drug interactions. Phytother Res. 2014 May;28(5):643-55. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5050. Epub 2013 Jul 30. PMID: 23897801.

Balashov PP, Kolesnikova AM. [Possibilities of pharmacotherapy in treatment of anxiety disorders in pregnancy]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2013;113(7):60-4. Russian. PMID: 23994924.

David Mischoulon. The Herbal Anxiolytics Kava and Valerian for Anxiety and Insomnia. Psychiatric Annals. 2013;32(1):55-60. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020101-09

Valerian (Herb/Suppl). https://reference.medscape.com/drug/all-heal-amantilla-valerian-344550

European Union herbal monograph on Valeriana officinalis L., aetheroleum. EMA/HMPC/278053/2015 Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). Published 2016. https://www.e-lactancia.org/media/papers/Valeriana-EMA2016_copia.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Mahmoudian A, Rajaei Z, Haghir H, Banihashemian S, Hami J. Effects of valerian consumption during pregnancy on cortical volume and the levels of zinc and copper in the brain tissue of mouse fetus. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Xue Bao. 2012 Apr;10(4):424-9. doi: 10.3736/jcim20120411. PMID: 22500716.

Naletov S. V. Clinical pharmacology of valerian preparations and European traditions of their use: the collapse of post-Soviet stereotypes. Review of foreign scientific sources. Ukrainian Medical Journal. https://umj.com.ua/uk/publikatsia-2757-klinicheskaya-farmakologiya-preparatov-valeriany-i-evropejskie-tradicii-ix-primeneniya-krushenie-postsovetskix-stereotipov-obzor-inostrannyx-nauchnyx-istochnikov

Chamomile use while Breastfeeding. https://www.drugs.com/breastfeeding/chamomile.html

Trabace L, Tucci P, Ciuffreda L. Natural relief of pregnancy-related symptoms and neonatal outcomes: above all do no harm. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;174:396-402.

Roman Chamomile. https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/natural/752.html#Effectiveness

Cuzzolin L, Francini-Pesenti F, Verlato G, Joppi M, Baldelli P, Benoni G. Use of herbal products among 392 Italian pregnant women: focus on pregnancy outcome. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010 Nov;19(11):1151-8. doi: 10.1002/pds.2040. PMID: 20872924.

Sarecka-Hujar B, Szulc-Musioł B. Herbal Medicines-Are They Effective and Safe during Pregnancy? Pharmaceutics. 2022 Jan 12;14(1):171. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14010171. PMID: 35057067; PMCID: PMC8802657.

Muñoz Balbontín Y, Stewart D, Shetty A, Fitton CA, McLay JS. Herbal Medicinal Product Use During Pregnancy and the Postnatal Period: A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2019 May;133(5):920-932. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003217. PMID: 30969204; PMCID: PMC6485309.

Abuhamdah S, Chazot PL. Lemon Balm and Lavender herbal essential oils: Old and new ways to treat emotional disorders? Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2008;19(4):221-226. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cacc.2008.05.005

Mathews IM, Eastwood J, Lamport DJ, Cozannet RL, Fanca-Berthon P, Williams CM. Clinical Efficacy and Tolerability of Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis) in Psychological Well-Being: A Review. Nutrients. 2024 Oct 18;16(20):3545. doi: 10.3390/nu16203545. PMID: 39458539; PMCID: PMC11510126.

Araj-Khodaei M, Noorbala AA, Yarani R, Emadi F, Emaratkar E, Faghihzadeh S, Parsian Z, Alijaniha F, Kamalinejad M, Naseri M. A double-blind, randomized pilot study for comparison of Melissa officinalis L. and Lavandula angustifolia Mill. with Fluoxetine for the treatment of depression. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020 Jul 3;20(1):207. doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-03003-5. PMID: 32620104; PMCID: PMC7333290.

Miraj S, Rafieian-Kopaei, Kiani S. Melissa officinalis L: A Review Study With an Antioxidant Prospective. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med. 2017 Jul;22(3):385-394. doi: 10.1177/2156587216663433. Epub 2016 Sep 11. PMID: 27620926; PMCID: PMC5871149.

Kennedy DA, Lupattelli A, Koren G, Nordeng H. Safety classification of herbal medicines used in pregnancy in a multinational study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2016 Mar 15;16:102. doi: 10.1186/s12906-016-1079-z. PMID: 26980526; PMCID: PMC4793610.

Vidal-García E, Vallhonrat-Bueno M, Pla-Consuegra F, Orta-Ramírez A. Efficacy of Lavender Essential Oil in Reducing Stress, Insomnia, and Anxiety in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Dec 5;12(23):2456. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12232456. PMID: 39685078; PMCID: PMC11641599.

Effati-Daryani F, Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi S, Mirghafourvand M, Taghizadeh M, Mohammadi A. Effect of Lavender Cream with or without Foot-bath on Anxiety, Stress and Depression in Pregnancy: a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Caring Sci. 2015 Mar 1;4(1):63-73. doi: 10.5681/jcs.2015.007. PMID: 25821760; PMCID: PMC4363653.

Seiiedi-Biarag L, Mirghafourvand M. The effect of lavender on mothers sleep quality in the postpartum period: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Complement Integr Med. 2022 Jan 24;20(3):513-520. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2021-0192. PMID: 35080353.