Maternal Knowledge and Practices in Caring for Children under Five with Pneumonia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Vietnam

Pediatrics受け取った 03 Feb 2025 受け入れられた 20 Feb 2025 オンラインで公開された 21 Feb 2025

Focusing on Biology, Medicine and Engineering ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Next Full Text

The Impact of Stress on Periodontal Health: A Biomarker-Based Review of Current Evidence

受け取った 03 Feb 2025 受け入れられた 20 Feb 2025 オンラインで公開された 21 Feb 2025

Introduction: Pneumonia remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in children under five in many low- and middle-income countries. Maternal knowledge and practices play a crucial role in early detection and management.

Objective: This study aimed to enhance evidence-based practices for pneumonia prevention in children.

Method: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 300 mothers of children under five receiving pneumonia treatment at the National Children’s Hospital in Hanoi, Vietnam. Data were collected through a structured interview questionnaire.

Results: 83% of mothers demonstrated comprehensive knowledge of pneumonia’s clinical definition; 90.7% correctly identified its primary causes; 82.7% recognized cough as a key symptom, and 87.7% understood potential complications; 98% reported appropriate responses to early pneumonia signs, with 93% adhering to correct symptomatic management. However, knowledge gaps persisted: only 71.7% identified pneumonia risk factors, 48.7% recognized chest indrawing as a critical symptom, and 50% understood supportive measures for cough management.

Conclusion: While the study highlights strengths in maternal knowledge and clinical practices, critical gaps remain, particularly in symptom recognition and risk factor awareness. Strengthening maternal education, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, and improving pediatric healthcare access may reduce pneumonia-related morbidity and mortality.

Pneumonia is an acute infectious disease of the lung parenchyma caused by bacteria, viruses, or fungi. It poses a significant health burden, particularly among children under five years of age-especially infants and neonates-due to their underdeveloped immune systems [,]. Pneumonia can be classified based on its causative agents, such as bacterial pneumonia (most commonly Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae), viral pneumonia (respiratory syncytial virus, influenza viruses), and fungal pneumonia (Pneumocystis jirovecii) in immunocompromised children [].

Globally, pneumonia remains the leading cause of mortality in children under five, accounting for approximately 15% of all child deaths, it's emphasizes the need for effective prevention and management strategies []. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 740,180 children under five died from pneumonia in 2019 [,]. In Vietnam, pneumonia is a primary cause of pediatric hospitalization, particularly during cold seasons and in regions with high air pollution []. Complications may include respiratory failure, permanent lung damage, and impaired physical development []. Delayed diagnosis and treatment can lead to severe outcomes such as Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS), lung abscesses, empyema, or sepsis []. Long-term sequelae may involve reduced pulmonary function, asthma, and chronic malnutrition due to compromised nutrient absorption []. Recurrent pneumonia in childhood also elevates the risk of chronic respiratory diseases in adulthood [].

Maternal knowledge is a critical component in ensuring prompt recognition of pneumonia symptoms and appropriate management, such as timely care-seeking and treatment adherence. It significantly influences pediatric pneumonia outcomes, particularly in low-income regions [,]. However, socioeconomic disparities, including occupation and education, exacerbate inequities in care-seeking behavior [,].

Globally, several studies have underscored the significance of maternal knowledge in preventing delays in health-seeking behavior for children with respiratory infections. For example, a cross-sectional study in Ethiopia demonstrated that mothers with higher educational attainment were significantly more likely to recognize pneumonia symptoms and seek treatment []. Patil, et al. [] in India also found that only 70% of caregivers recognized early pneumonia symptoms, reflecting a widespread need for improved public awareness. Similar findings have been reported in Southeast Asia, where improving maternal awareness of pneumonia has led to improved child health outcomes [,]. Chheng and Thanattheerakul [] in Cambodia reported that 68% of mothers demonstrated accurate pneumonia-related knowledge, emphasizing the necessity for community-based health interventions.

In Vietnam, multiple studies have assessed maternal Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAP) in managing childhood pneumonia. A study by Nguyen TTN [] in Bac Ninh revealed that only 54.8% of mothers possessed a comprehensive knowledge of pneumonia, underscoring the urgent need for health education. Research at Children’s Hospital 1 in Ho Chi Minh City highlighted limited maternal recognition of critical danger signs, particularly chest indrawing [].

These findings underscore the critical importance of enhancing maternal awareness and practices in pneumonia care. Improved maternal knowledge enables early symptom recognition, appropriate home management, and timely healthcare access, thereby reducing complications and mortality []. Despite these documented associations, studies exploring the link between maternal knowledge and actual practices in Vietnam remain limited. Therefore, this study aimed to assess maternal knowledge and practices regarding pneumonia management among mothers of children under five and to examine how socioeconomic and demographic factors affect maternal knowledge. Ultimately, understanding these factors is essential for designing targeted interventions that can optimize pediatric care quality and outcomes.

A cross-sectional study was conducted among mothers of children under five years old diagnosed with pneumonia and receiving treatment at the Department of Voluntary Treatment C, National Children’s Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam, from June to August 2022.

Inclusion criteria

- Mothers aged ≥18 years.

- Complete and clear medical records of children under five diagnosed with mild to moderate pneumonia at the study site.

- Willingness to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

- Children outside the study’s age range.

- Mothers declining participation.

- Children with pneumonia complicated by severe concurrent infections.

Eligible mothers of children under five with pneumonia at the study site were systematically enrolled until a sample size of 300 participants was achieved. Data were collected through:

- Medical records: Clinical and paraclinical data.

- Structured interviews: A validated questionnaire aligned with study objectives and variables (Supplementary File S1).

Questionnaire Validation: The initial version of the questionnaire was reviewed by two pediatric specialists and one epidemiologist to ensure content validity. A pilot test with 30 mothers (excluded from the final analysis) was performed to assess the clarity and consistency of the items, which resulted in minor modifications. Internal consistency was found to be acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78).

Mothers’ occupations were grouped into "officials/employees" (formal sector, stable income) and "workers/farmers/housework/others" (informal/unstable income) to reflect Socioeconomic Status (SES), which influences healthcare access and health literacy. This categorization follows local labor statistics, where women who are not in formal employment are grouped together due to similar working conditions, socioeconomic backgrounds, and time availability for childcare.

Demographic variables: Maternal age, ethnicity, occupation, educational level, information sources, and prior experience caring for children with pneumonia.

Knowledge and practice variables: Understanding of pneumonia etiology, symptoms, risk factors, diagnosis and initial management, temperature monitoring, cough management, hygiene practices, and nutritional support.

Knowledge score: Assessed through multiple-choice and open-ended questions on pneumonia. A cumulative score of ≥ 70% was considered adequate knowledge.

Practice score: Based on reported health-seeking behaviors (time to hospital visit, adherence to medical instructions) and home-care practices (fluid intake, monitoring fever).

Knowledge assessment: A 15-item questionnaire (adapted from prior studies [,] scored responses as correct (1 point) or incorrect (0 points). Mothers scoring 12–15 points were classified as having adequate knowledge; scores ≤ 11 indicated inadequate knowledge.

Practice assessment: A 5-item tool evaluated practices on a 3-point scale (0: not performed; 1: partially performed; 2: fully performed). Scores ≥ 8/10 defined appropriate practices.

Data were encoded, cleaned using EpiData, and analyzed statistically using Stata software.

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Children's Hospital, located in Hanoi, Vietnam (Approval no. 69/2022/NCH). The research team clearly explained the study’s purpose to all participants. The study was conducted only with participants’ voluntary consent. Participants retained the right to withdraw without repercussions to their children's treatment standing. All personal information was anonymized and kept confidential, and it was used solely for research purposes.

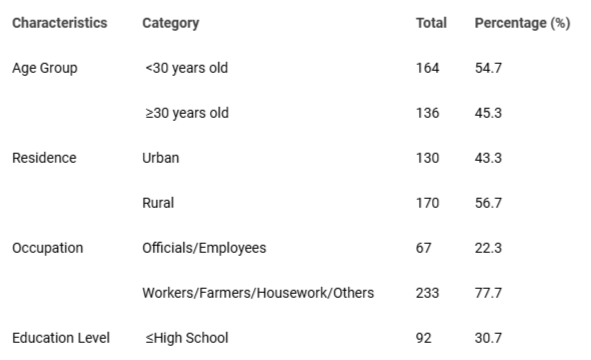

As demonstrated in Table 1, the majority of parents (54.7%) were under 30 years of age, with a predominant concentration in rural areas (56.7%). Occupational distribution revealed that only 22.3% of mothers were civil servants or government employees, while 77.7% identified as manual laborers, farmers, homemakers, or held other occupations. Regarding educational attainment, 69.3% of participants had completed high school or higher.

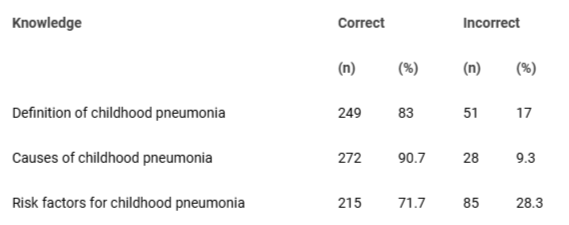

As shown in Table 2, the assessment of maternal knowledge regarding pneumonia revealed that 83% of mothers demonstrated an accurate understanding of the clinical definition of pneumonia, 90.7% correctly identified its etiology, and 71.7% recognized associated risk factors.

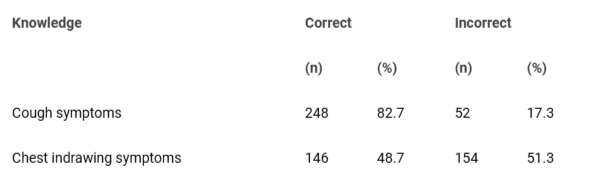

As shown in Table 3, the assessment results indicate that a majority of mothers demonstrated accurate knowledge of cough as a symptom of pneumonia (82.7%) and its complications (87.7%). However, only 48.7% recognized chest indrawing (subcostal retraction) as a critical clinical sign of pneumonia.

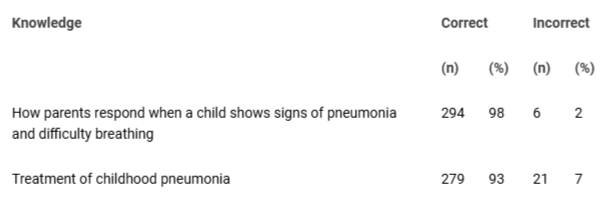

The results of Table 4 show that the percentage of mothers with correct knowledge about how to handle children with signs of pneumonia is 98% and the percentage of correct treatment is 93%.

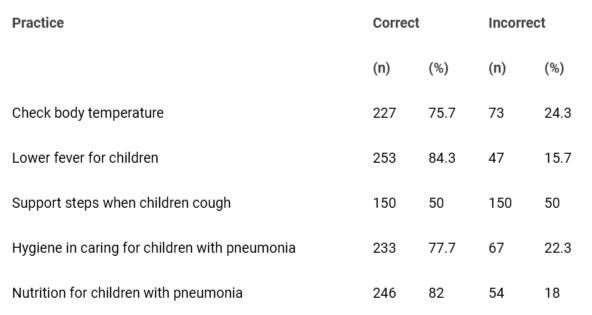

As shown in Table 5, the results indicate that 75.7% of mothers correctly practiced temperature monitoring for their children, 84.3% effectively managed fever, 77.7% maintained proper hygiene during pneumonia, 82% followed recommended nutritional guidelines, and 50% implemented supportive measures for cough management.

This study aimed to evaluate maternal knowledge and practices in caring for children under five with pneumonia at the National Children’s Hospital, Hanoi, Vietnam. The findings provide critical insights into caregivers’ awareness and management capabilities, revealing notable demographic and care-practice disparities compared to prior research.

Among the participants, 54.7% of mothers were under 30 years old, a finding consistent with Tran TL’s 2017 study (64.5%) conducted at Quang Ninh General Hospital []. This reflects the typical childbearing age in Vietnam and suggests potential correlations with healthcare information accessibility. Additionally, 56.7% of participants resided in rural areas, aligning with the findings of Tran DH, et al. [] in Can Tho and Tran TL []. This trend highlights potential disparities in living conditions, economic status, and healthcare access between urban and rural regions. Moreover, 77.7% of mothers were engaged in agriculture, homemaking, or informal sectors, while only 22.3% were civil servants. It showed that mothers with formal employment had higher knowledge scores, suggesting SES impacts healthcare literacy. This underscores the need for targeted health education programs that address the socioeconomic challenges affecting pediatric healthcare in Vietnam for these populations.

The proportion of mothers with accurate knowledge of the definition of pneumonia reached 83%, which is higher than the findings of Nguyen TTN’s 2020 study in Tu Son and Tran TL’s 2017 study at Quang Ninh General Hospital, which reported approximately 54.8% [,]. This rate also significantly exceeds that of international studies, such as Chheng & Thanattheerakul’s 2021 study in Cambodia (68%) [] and Patil, et al.’s 2021 study in India (70%) []. These findings suggest an improvement in community health education and awareness programs in Vietnam. However, further efforts should focus on more complex topics, such as identifying severe symptoms, to enhance early detection and timely management of the disease.

Regarding pneumonia symptom recognition, 98% of mothers correctly identified common symptoms such as cough, fever, and wheezing. It is higher than the 77% reported in Tran DH, et al.’s 2013 study [] and the 72% reported in Trinh HA’s 2018 study at Can Tho Children's Hospital []. These results indicate a progressive improvement in maternal awareness of pneumonia over time, likely due to the widespread dissemination of information through mass media and healthcare education initiatives.

However, knowledge of severe pneumonia symptoms remains limited, particularly chest indrawing, which was recognized by only 48.7% of mothers. This reflects a lack of awareness regarding critical warning signs of the disease. These findings are consistent with Nguyen TN, et al.'s 2015 study, which highlighted insufficient dissemination of information about severe pneumonia symptoms []. Moreover, these results are lower than those reported in O'Brien, et al.'s 2019 study on the causes of severe pneumonia in children []. Their findings indicated that parents in developed countries had a higher awareness of chest indrawing as a symptom due to better access to healthcare systems []. Therefore, it is crucial to enhance maternal education and guidance in Vietnam to improve the recognition of severe symptoms and ensure that children receive timely medical care.

The proportion of mothers who knew how to manage pneumonia symptoms in children reached 98%, while 93% were aware of essential interventions such as fever reduction, back-patting to aid sputum clearance, instructing children on hygienic coughing, and maintaining an appropriate diet based on medical advice. These findings suggest an improved level of information accessibility and parental awareness regarding the importance of seeking medical care for their children. Notably, these rates are higher than those reported in the study by Trinh HA [] at Can Tho Children's Hospital (56%) and the study by Fancourt, et al. [] in Africa (74%). This reflects a growing awareness among parents in Vietnam; however, further improvements are needed through community health education programs.

Despite these advancements, certain gaps in caregiving practices remain, particularly in providing support for coughing episodes (50%) and nutritional knowledge (77%). Compared to the 54.9% reported in Nguyen TTN’s 2020 study, the proportion of mothers demonstrating proper caregiving practices in this study is significantly higher. This difference may be attributed to variations in study periods and the increasing prevalence of health education campaigns in recent years [,].

A key concern is that some mothers still lack adequate knowledge regarding nutritional management for children with pneumonia. Only 77% recognized the need to enhance protein- and energy-rich food intake []. This underscores the necessity of strengthening nutritional education in pneumonia management to mitigate the risk of malnutrition and accelerate recovery in affected children.

As a cross-sectional study, we can only infer associations rather than causality. Our sample, drawn from a single hospital, may not be representative of all mothers in Vietnam, raising the possibility of selection bias. Mothers who have access to this hospital might differ in their knowledge levels compared to those in more remote regions. Therefore, future studies with broader sampling frames and longitudinal designs are recommended to better capture how maternal knowledge evolves over time and to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions.

Maternal knowledge and practices regarding pneumonia are influenced by multiple factors, including education level, occupation, and broader socioeconomic conditions. Strengthening educational programs for pneumonia prevention and management among disadvantaged populations is critical. These findings have significant implications for identifying areas that require improvement in maternal awareness and practices related to pneumonia care in children. Also, these insights can inform the design of health education programs that emphasize the early identification of danger signs and the promotion of optimal nutritional care practices. Further multicenter research is needed to validate these findings and to inform policy interventions that could significantly reduce pneumonia-related morbidity and mortality in children under five.

This cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Selection bias may arise as participants were recruited from a single hospital, potentially excluding marginalized populations. Limited sample size necessitates caution in generalizing results.

Future longitudinal or multi-center studies are needed to validate findings to investigate the critical impacts of maternal knowledge and practices on the care of children with pneumonia. Additionally, research may elucidate the factors influencing care and treatment protocols to mitigate the adverse outcomes of pediatric pneumonia.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

D. N. and V. T. P. conceived and designed the evaluation and drafted the manuscript. X. H. D. and P. P. N. participated in designing the evaluation, performed parts of the statistical analysis, and helped to draft the manuscript. T. D. N. reevaluated the clinical data, revised the manuscript performed the statistical analysis, and revised the manuscript. V. T. P. collected the clinical data, interpreted them, and revised the manuscript. X. H. D. re-analyzed the clinical and statistical data and revised the manuscript. P. P. N. had a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data availability statement: All the data available is provided in this paper.

Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 May;86(5):408-16. doi: 10.2471/blt.07.048769. PMID: 18545744; PMCID: PMC2647437.

Chheng R, Thanattheerakul C. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices to Prevent Pneumonia among Caregivers of Children Aged Under 5 Years Old in Cambodia. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications. 2021;2581-6187.

Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study Group. Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet. 2019 Aug 31;394(10200):757-779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30721-4. Epub 2019 Jun 27. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Aug 31;394(10200):736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32010-0. PMID: 31257127; PMCID: PMC6727070.

Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, O'Brien KL, Campbell H, Black RE. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013 Apr 20;381(9875):1405-1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. Epub 2013 Apr 12. PMID: 23582727; PMCID: PMC7159282.

World Health Organization. Pneumonia in children: Global burden and prevention strategies. WHO. 2021.

Murarkar S, Gothankar J, Doke P, Dhumale G, Pore PD, Lalwani S, Quraishi S, Patil RS, Waghachavare V, Dhobale R, Rasote K, Palkar S, Malshe N, Deshmukh R. Prevalence of the Acute Respiratory Infections and Associated Factors in the Rural Areas and Urban Slum Areas of Western Maharashtra, India: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Front Public Health. 2021 Oct 26;9:723807. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.723807. PMID: 34765581; PMCID: PMC8576147.

Nguyen TTN. Knowledge, attitude, and practice in caring for children under five years old with pneumonia and related factors [Master’s thesis]. Thang Long University; 2020.

Tran DH, Nguyen TDT. Survey on mothers’ knowledge of child care for children with pneumonia at Can Tho Children's Hospital. Journal of Practical Medicine. 2013;6:23–7.

Bush A, Zar HJ. WHO universal definition of severe pneumonia—time for change? Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(1):12–3.

Lodha R, Kabra SK. Newer developments in childhood pneumonia. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56(4):281–8.

GBD 2015 LRI Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory tract infections in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Nov;17(11):1133-1161. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30396-1. Epub 2017 Aug 23. PMID: 28843578; PMCID: PMC5666185.

Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 May;86(5):408-16. doi: 10.2471/blt.07.048769. PMID: 18545744; PMCID: PMC2647437.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Pneumonia in Children: A Leading Killer that Can Be Stopped. New York: UNICEF; 2020. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/pneumonia-in-children-a-leading-killer-that-can-be-stopped/

Jackson S, Mathews T, Pienaar E. Risk factors for severe pneumonia in children in low-resource settings: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(8):e006564.

Smith KR, McCracken JP, Weber MW. Effect of air pollution on pneumonia-related mortality in children. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(3):037002.

Tona E, Mesfin F, Chisha Y. Mothers’ knowledge of pneumonia and associated factors among under-five children in rural Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):123. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8172-6

Le TT, Anh NT, Tran BH, Nguyen TT. Maternal knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding pneumonia among children under five in Central Vietnam. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2019;50(4):728–736.

Islam M, Rahman M, Halim A, Hussain S, Tarafder T. Impact of maternal awareness on childhood pneumonia outcomes in Southeastern Asia: A multi-country analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(8):906–915. doi:10.1111/tmi.13611

Fancourt N, Deloria-Knoll M, Barger-Kamate B. Community understanding and management of pneumonia in children under five in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232198.

Trinh HA. Survey on parental knowledge about pediatric pneumonia in children under 5 years old at the outpatient department, Can Tho Children's Hospital in 2018. 2018.

Tran TL. Awareness of mothers about caring for children under 5 years old with pneumonia at the Pediatric Department, Quang Ninh General Hospital in 2017. Journal of Medical Nursing. 2017;2(2):44-52.

Nguyen TN, Phan VN, Vo TTH. Clinical and paraclinical characteristics and factors related to severe pneumonia in children aged 2 months to 5 years at Vinh Long General Hospital. 2015.

Nair H, Simões EAF, Laxminarayan R, Levine OS. Global burden of childhood pneumonia: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(3):e342-e351 . doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30529-6.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for the management of childhood pneumonia. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090000

Thai ND, Xuyen DH, Phuong NP, Viet PT. Maternal Knowledge and Practices in Caring for Children under Five with Pneumonia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Vietnam. IgMin Res. February 21, 2025; 3(2): 091-096. IgMin ID: igmin287; DOI:10.61927/igmin287; Available at: igmin.link/p287

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

1General Clinic, National Institute for Control of Vaccines and Biologicals, Hanoi City, Vietnam

2Department of Physiology, Vietnam University of Traditional Medicine, Hanoi City, Vietnam

3Tue Tinh Hanoi College of Medicine and Pharmacy, Hanoi City, Vietnam

Address Correspondence:

Thai Nguyen Duy, General Clinic, National Institute for Control of Vaccines and Biologicals, Hanoi City, Vietnam, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Thai ND, Xuyen DH, Phuong NP, Viet PT. Maternal Knowledge and Practices in Caring for Children under Five with Pneumonia: A Cross-Sectional Study in Vietnam. IgMin Res. February 21, 2025; 3(2): 091-096. IgMin ID: igmin287; DOI:10.61927/igmin287; Available at: igmin.link/p287

Copyright: © 2025 Thai ND, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of study subjects....

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of study subjects....

Table 2: Correct knowledge about childhood pneumonia of stu...

Table 2: Correct knowledge about childhood pneumonia of stu...

Table 3: Correct knowledge about symptoms of pneumonia in c...

Table 3: Correct knowledge about symptoms of pneumonia in c...

Table 4: Correct knowledge about how to handle children wit...

Table 4: Correct knowledge about how to handle children wit...

Table 5: Practices for caring for children with pneumonia....

Table 5: Practices for caring for children with pneumonia....

Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 May;86(5):408-16. doi: 10.2471/blt.07.048769. PMID: 18545744; PMCID: PMC2647437.

Chheng R, Thanattheerakul C. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices to Prevent Pneumonia among Caregivers of Children Aged Under 5 Years Old in Cambodia. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications. 2021;2581-6187.

Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study Group. Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet. 2019 Aug 31;394(10200):757-779. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30721-4. Epub 2019 Jun 27. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Aug 31;394(10200):736. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32010-0. PMID: 31257127; PMCID: PMC6727070.

Walker CLF, Rudan I, Liu L, Nair H, Theodoratou E, Bhutta ZA, O'Brien KL, Campbell H, Black RE. Global burden of childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet. 2013 Apr 20;381(9875):1405-1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60222-6. Epub 2013 Apr 12. PMID: 23582727; PMCID: PMC7159282.

World Health Organization. Pneumonia in children: Global burden and prevention strategies. WHO. 2021.

Murarkar S, Gothankar J, Doke P, Dhumale G, Pore PD, Lalwani S, Quraishi S, Patil RS, Waghachavare V, Dhobale R, Rasote K, Palkar S, Malshe N, Deshmukh R. Prevalence of the Acute Respiratory Infections and Associated Factors in the Rural Areas and Urban Slum Areas of Western Maharashtra, India: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Front Public Health. 2021 Oct 26;9:723807. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.723807. PMID: 34765581; PMCID: PMC8576147.

Nguyen TTN. Knowledge, attitude, and practice in caring for children under five years old with pneumonia and related factors [Master’s thesis]. Thang Long University; 2020.

Tran DH, Nguyen TDT. Survey on mothers’ knowledge of child care for children with pneumonia at Can Tho Children's Hospital. Journal of Practical Medicine. 2013;6:23–7.

Bush A, Zar HJ. WHO universal definition of severe pneumonia—time for change? Lancet Respir Med. 2019;7(1):12–3.

Lodha R, Kabra SK. Newer developments in childhood pneumonia. Indian Pediatr. 2019;56(4):281–8.

GBD 2015 LRI Collaborators. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory tract infections in 195 countries: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Nov;17(11):1133-1161. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30396-1. Epub 2017 Aug 23. PMID: 28843578; PMCID: PMC5666185.

Rudan I, Boschi-Pinto C, Biloglav Z, Mulholland K, Campbell H. Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 May;86(5):408-16. doi: 10.2471/blt.07.048769. PMID: 18545744; PMCID: PMC2647437.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Pneumonia in Children: A Leading Killer that Can Be Stopped. New York: UNICEF; 2020. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/resources/pneumonia-in-children-a-leading-killer-that-can-be-stopped/

Jackson S, Mathews T, Pienaar E. Risk factors for severe pneumonia in children in low-resource settings: A systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2021;6(8):e006564.

Smith KR, McCracken JP, Weber MW. Effect of air pollution on pneumonia-related mortality in children. Environ Health Perspect. 2018;126(3):037002.

Tona E, Mesfin F, Chisha Y. Mothers’ knowledge of pneumonia and associated factors among under-five children in rural Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):123. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8172-6

Le TT, Anh NT, Tran BH, Nguyen TT. Maternal knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding pneumonia among children under five in Central Vietnam. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2019;50(4):728–736.

Islam M, Rahman M, Halim A, Hussain S, Tarafder T. Impact of maternal awareness on childhood pneumonia outcomes in Southeastern Asia: A multi-country analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26(8):906–915. doi:10.1111/tmi.13611

Fancourt N, Deloria-Knoll M, Barger-Kamate B. Community understanding and management of pneumonia in children under five in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232198.

Trinh HA. Survey on parental knowledge about pediatric pneumonia in children under 5 years old at the outpatient department, Can Tho Children's Hospital in 2018. 2018.

Tran TL. Awareness of mothers about caring for children under 5 years old with pneumonia at the Pediatric Department, Quang Ninh General Hospital in 2017. Journal of Medical Nursing. 2017;2(2):44-52.

Nguyen TN, Phan VN, Vo TTH. Clinical and paraclinical characteristics and factors related to severe pneumonia in children aged 2 months to 5 years at Vinh Long General Hospital. 2015.

Nair H, Simões EAF, Laxminarayan R, Levine OS. Global burden of childhood pneumonia: a systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(3):e342-e351 . doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30529-6.

World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for the management of childhood pneumonia. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090000