The Role of CCL18 in Rheumatoid Arthritis Diseases

Clinical Medicine受け取った 26 Dec 2024 受け入れられた 16 Jan 2025 オンラインで公開された 17 Jan 2025

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Previous Full Text

New HMPV Virus Outbreak: Emerging Concerns and Public Health Implications

受け取った 26 Dec 2024 受け入れられた 16 Jan 2025 オンラインで公開された 17 Jan 2025

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic auto-immune disease that mostly occurs in joint space with remarkably painful swelling. RA detail pathologies remain unclear, but several C-C motif chemokines factors and Interleukin have been identified as associated factors and correlated disease-associate activities (such as CCL2, CCL18, IL-6). Among these factors, increasing evidence indicates CCL18 could be an appropriate drug target, as it is highly correlated with disease-associated activities (DAS28) (elevated level of CCL18 in both patient serum and local synovial fluids). High-concentration CCL18 in synovial fluids has been reported to facilitate pro-inflammation factor production, finally resulting in painful swelling in joint space. In vivo studies showed significant drug efficiency with anti-TNF-a treatment (CCl18 suppression). Most current approved drugs target TNF, IL-6, or other factors, but do not target CCL18 directly or indirectly. From this perspective, CCL18 has been believed to be a new target for RA therapeutic drug development.

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation of the synovium, cartilage, and bones. Primarily, RA targets the joints, leading to painful swelling and inflammation. Extensive research over the decades has identified numerous chemokine ligands associated with RA pathogenesis. Among these chemokines, three cytokines are the most well-studied correlated with RA: CCL3, IL-6, and CCL21 (along with its receptor CCR7) [-]. However, none of these chemokines have been definitively established as key factors in RA pathogenesis.

Zhang, et al. [] demonstrated that CCL3 was highly expressed in the cytoplasm of CD4+ T cells within synovial tissues of RA patients. Once stimulation by pro-inflammatory factors, synovial cells are activated to generate CCL3. This CCL3 upregulation recruits inflammatory cells to the joint tissue, resulting in the secretion of inflammatory factors into the synovial microenvironment and perpetuating the inflammatory response characteristic of RA []. Despite its role in promoting and facilitating inflammation, CCL3 is not considered an ideal diagnostic or therapeutic drug target due to its complicated and limited-known interactions between immune and non-immune cells in RA synovial tissue and its microenvironment [].

As for IL-6, it has long been believed as a central cytokine/factor in RA pathogenesis reasoning for its contribution to joint destruction via the enrichment of T-helper 17 (Th17) cells and the inflammatory factors promotion []. In 2020, Raemdonck, et al. reported that elevated levels of CCL21 in synovial fluid activate monokines, which may differentiate naïve T cells into Th17 cells. Th17 cells are a subtype of CD4 T cells that produce chemokines belonging to the interleukin family. These cells are believed to play a significant role in the bone destruction associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Notably, even though both CCL19 and CCL21 are enriched in RA specimens, data shows only CCL21 responds to RA pathogenesis via receptor CCR7 and its associated signaling pathways [].

Despite numerous clinical studies identifying various chemokines, the dominant factor underlying RA pathogenesis and its precise mechanisms remain unclear. Recent advancements in technology and measurement techniques have provided growing evidence demonstrating that Chemokine Ligand 18 (CCL18) may respond and play a dominant role in RA pathogenically development [,]. CCL18 is produced by Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells and activated macrophages, and is proven to attract T-cell infiltration to joint tissues [,,].

CCL18 is a C-C motif DNA binding ligand, located on chromosome 17 with 89 amino acids encoding (including 20 amino-acid long signals for the peptides section) []. Due to structural similarities with CCL3, CCL18 shares certain overlapping biological functions. Some researchers believe that CCL18 is the product of a gene fusion event involving CCL3 and other genes that have accumulated mutations during human evolution [-]. This suggests that CCL18 may represent a more potent version of CCL3, potentially playing an upstream regulatory role in CCL3-mediated biological functions. In cancer research, CCL18 has been proven to correlate positively with cancer cell metastasis, particularly in breast cancer, where it binds to its identified receptor PITPMN3 to induce Src- and Pyk2-mediated signaling pathways [,]. Emerging evidence suggests that CCL18 may contribute to RA pathogenesis by facilitating the migration of Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes (FLS).

Compared with the most studied CCL3 in RA, CCL18 plays a more complex role in not only attracting immune cells to joint tissue causing inflammation but also acting as a regulator for immune response. This might be the reason why CCL3 is proven not to be an appropriate diagnostic or therapeutic target as its limited role in immune regulation. This suggests CCL18 might have the potential to outperform CCL3 at this point as CCL18 has more complex genetic and protein structures []. As for IL-6, it has been believed a central RA cytokine for decades and has been developed with multiple antibody-based drugs based on it. Whereas, reports showed that only approximately 50% of RA patients have clinical improvement after IL-6-targeted drug treatment (such as TNFα inhibitor) [,]. This mini-review will summarize the current studies about the association between serum/synovial CCL18 and RA pathogenesis and explore the potential of CCL18 to be a new therapeutic research target of RA.

In 2007, Antoine, et al. (2007) first reported the circulating serum levels of CCL18 were elevated in RA patients while not of CXCL16 (another chemokines that facilitate T cell attraction by APC). In the studies, serum CCL18 level was found to have a positive correlation with disease activity, joint damage, and progression of joint damage. Antoine, et al. (2007) also implemented an infliximab-treatment test (anti-TNF- α treatment test to suppress both CCL18 and CXCL16) serum CCL18 level for 14 weeks. It resulted that 95% of patients have a significant drop of both CCL18 and CXCL16 (but a decrease of CXCL16 is limited). After 2 weeks, 35% of patients' CXCL16 increased, and only 65% of patients' CXCL16 remained decreased, suggesting that CXCL16 reduction is not correlated with disease activity []. This result indicating the serum level of CCL18 is highly correlated with disease activity but not CXCL16. Radstake, et al. (2005) also found that mRNA levels of CCL17 and CCL19 also remarkably increased in RA patients’ dendritic cells (both immature and mature dendritic cells) along with CCL18. [] In 2019, Mo, et al. recruited 83 RA patients and reported that serum CCL18 levels were significantly higher than healthy control (RA: n = 83, 107 (80∼126) ng/mL; healthy: n = 25, 51 (29∼70) ng/mL). More importantly, serum CCL18 significantly correlated with CRP (r = 0.385, p < 0.001), ESR (r = 0.239, p = 0.03), PrGA (r = 0.249, p = 0.03), DAS28-CRP (r = 0.368, p = 0.001), DAS28-ESR (r = 0.336, p = 0.003), SDAI (r = 0.360, p = 0.001), CDAI (r = 0.328, p = 0.004) and HAQ (r = 0.325, p = 0.004). This indicates that the evaluated CCL18 level might respond to RA pathogenesis [].

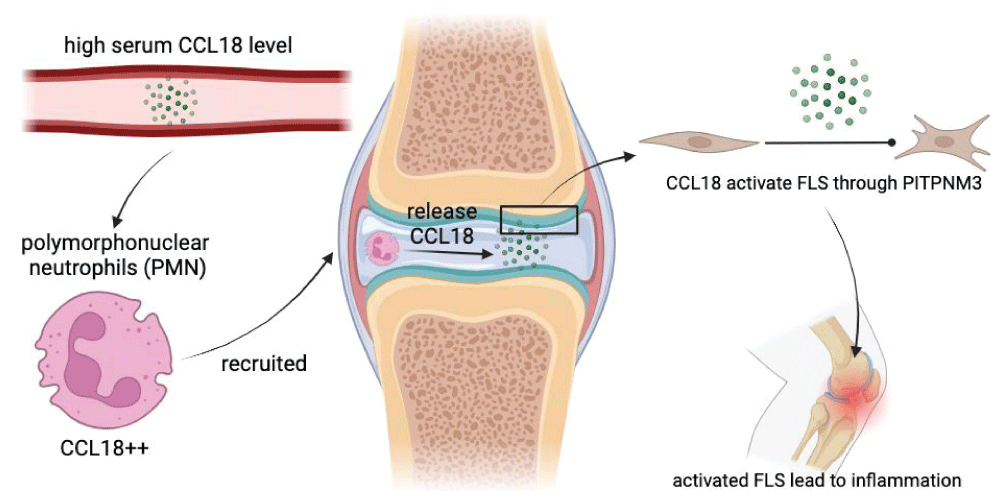

Besides increased levels of CCL18 in serum, CCL18 level is also found to increase in synovial fluids []. The synovial fluids CCL18 might be incoming from circulating serum polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN, the predominant cell type recruited into synovial fluid). Judith, et al. (2007) investigated the CCL18 production in PMN and found that PMN significantly increases CCL18 production when recruited into synovial fluid []. The high level of CCL18 in RA patient’s synovial fluid might cause pathogenic reaction, such as Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes (FLS) activation [,]. FLS are mesenchymal-derived cells that are critical for joint health, as FLS can secret certain components into synovial fluid and articular cartilage. FLS activation could lead to a secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (such as TNF- α and IL-1β) and ultimately cause RA symptoms and disease activity, such as swelling []. The CCL18 might activate FLS through phosphatidylinositol transfer membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol transfer protein 3 (PITPNM3, a CCL18 receptor) (the activation mechanism is still unclear, but limited evidence suggests it could be due to phosphatase and tension homolog deleted on chromosome 10, or called PTEN) [,,]. Takayasu, et al. (2013) showed the increased level of PITPNM3 in RA-FLS and Tan, et al (2021) also proved the increased expression of PITPNM3 in health FLS under CCL18 induction [,] (Figure 1). (Yuebin Tan, et al. 2021). In 2019, Mo, et al. reported that CCL18 levels in synovial are significantly higher than its level in serum (n = 31, 719 (415∼1271) ng/mL) []. This suggests that the CCL18 were filtered and enriched in synovial from serum, which is correlated with the opinion from Weyand [].

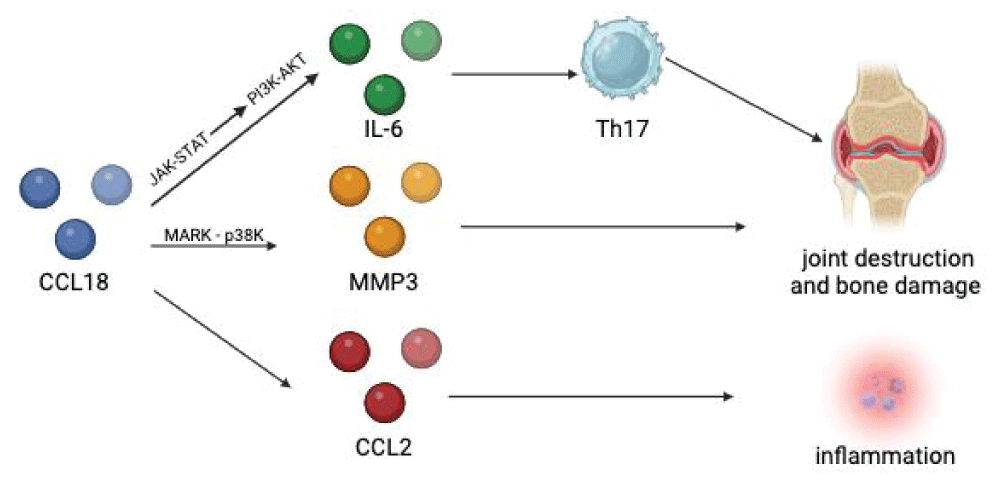

Several chemokines have been identified as factors associated with CCL18 in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mo, et al. (2016) reported that the secretion of IL-6, CCL2, and MMP3 in synovial tissue significantly increased following stimulation with CCL18 (500 ng/mL) for 48 hours []. This finding suggests that CCL18 acts upstream of CCL2, MMP3, and IL-6 in the regulation of signaling pathways, all of which are implicated in RA-related inflammation and joint destruction (Figure 2).

CCL2 is considered a trigger for multiple signaling pathways through its interaction with its receptor, CCR2, ultimately leading to inflammation and T-cell migration toward RA synovial tissue []. However, a clinical trial of a CCL2-blocking antibody (ABN912) demonstrated no detectable clinical improvement, indicating that CCL2 is not a dominant factor in RA pathogenesis []. These findings imply that the key pathogenic factors may be upstream of CCL2 in the signaling pathway.

MMP3 is a well-known enzyme that plays a key role in joint destruction and bone damage and is currently being evaluated in clinical trials as a biomarker for joint damage []. IL-6, on the other hand, has been considered a central cytokine in RA pathogenesis over the past decade due to its role in promoting inflammation through the activation of immune cells. IL-6 has been shown to activate CD4+ T cells, leading to the differentiation of Th17 cells, which contribute to joint destruction [].

IL-6 has been a major target for drug development, resulting in the FDA approval of antibody-based therapies such as Tocilizumab and Sarilumab. However, reports indicate that a subset of patients experience cytokine storms following IL-6-targeted treatment, and approximately 50% of RA patients exhibit non-responsiveness to these therapies. These findings suggest that IL-6 may not be the optimal drug target for all RA patients [,].

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) pathogenesis involves four major classical signaling pathways: NF-κB, MAPK, PI3K-AKT, Wnt, and JAK-STAT []. CCL18 plays a critical role in regulating these pathways. PITPNM3 has been identified as the receptor for CCL18 in RA []. Zeng, et al. (2022) demonstrated that CCL18-induced fibroblast activation is mediated by PITPNM3, which subsequently activates the NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation []. This activation facilitates the migration of fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS), a process mediated by PITPNM3, a well-studied cell migration factor, particularly in cancer cells.

Phosphorylated MAPKs are known to induce cytokine activation in RA, with p38 kinase playing a significant role in regulating MMP3 expression in fibroblasts. This regulation occurs through Fas protein-mediated inhibition of apoptosis and T cell recruitment in synovial tissues. Overexpression of MMP3 contributes to joint destruction [-].

The PI3K-AKT pathway involves two key genes for signal regulation: phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase B (PKB, or AKT). PI3K phosphorylates PIP2 to produce PIP3, while PTEN dephosphorylates PIP3 back to PIP2, thereby ending the PI3K signaling cycle at the point. The PI3K-AKT signaling pathway has been proven to strongly correlate with RA development, primarily due to its role in abnormal FLS proliferation and the stimulation of inflammatory factor expression, such as IL-6, which operates downstream of CCL18 []. Zhou, et al. [] demonstrated that PTEN loss (which makes PIP3 cannot dephosphorylate and accumulated in joint tissue, resulting in IL-6 overexpression) leads to abnormal FLS proliferation and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, a finding consistent with Mo, et al.’s observation of FLS proliferation following CCL18 stimulation (CCL18 enrichment stimulate IL-6 overexpression in FLS). These findings suggest that CCL18 may influence PTEN regulation. Experimental overexpression of PTEN has been shown to mitigate RA-related damage [,].

Recent studies have also highlighted a strong correlation between abnormal activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway and RA progression. This pathway comprises four key members: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TyK2. Among these four members, JAK1 has been implicated in IL-6 recruitment for RA pathogenesis, while TyK2 activation by IL-6 contributes to bone damage []. TyK2 has been targeted for drug development. Clinical studies have demonstrated a significant upregulation of JAK2 in the synovial tissue of RA patients, and experimental inhibition of JAK2 has been shown to reduce RA damage and improve synovial inflammation [,]. Recent findings by Vomero, et al. (2022) revealed that the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib reduces autophagy in FLS from RA patients by blocking downstream JAK signaling involving JAK3/JAK1 and, to some extent, JAK2 []. Additionally, JAK activation can stimulate the PI3K-AKT pathway via receptor phosphorylation [-]. These observations suggest that CCL18 may play a similar role in the JAK-STAT signaling pathway by recruiting IL-6 and activating the PI3K-AKT pathway [] (Figure 2).

Currently, there are no FDA-approved CCL18-based methods to indicate the duration of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). However, multiple clinical studies indirectly prove the potential for a CCL18-based method for RA duration measurement. Leishout, et al. (2007) recruited 44 RA patients and measured CCL18 levels before and after anti-TNF-alpha treatment (paired test). Results showed that CCL18 level decreased upon anti-TNF-alpha treatment (infliximab) and this decrease correlates with RA clinical improvement. 95% of RA patients had a significant drop in CCL18 level in the first 2 weeks and had a highly positive correlation with RA clinical improvement parameters, such as DAS-28 (Disease Activity Score). These clinical studies demonstrated the CCL18 level response to RA clinical disease development and showed the potential of CCL18 to be an RA indicator in clinical trials [].

As described, CCL18 plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of RA, and its levels are associated with certain characteristics of the disease. In addition to CCL18, other RA-related biomarkers such as anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies (anti-CCP), Rheumatoid Factor (RF), and C-Reactive Protein (CRP) can be measured. Integrating CCL18 levels with these biomarkers and clinical indicators (such as DAS28, Health Assessment Questionnaire HAQ-DI, etc.) may help provide a more accurate assessment of RA duration and progression. The duration of RA is closely related to disease activity and joint damage severity. By monitoring changes in CCL18 levels, combined with disease activity scores and imaging results, one can indirectly infer the duration of RA. For example, a sustained increase in CCL18 levels may suggest that the disease is in an active or progressive phase.

Long-term monitoring is required for conducting long-term longitudinal follow-up studies on RA patients, regularly measuring CCL-18 levels, and recording their disease duration information. By analyzing the trend of changes in CCL-18 levels over time and its relationship with disease duration, an association model between CCL-18 levels and RA duration can be established. This method requires a large sample size and long-term data accumulation. There may be individual differences in RA duration and CCL-18 levels among different patients. In longitudinal follow-up, individualized disease duration assessment and prediction can be made based on each patient's specific situation, combined with changes in their CCL-18 levels [].

Further research into the role of CCL-18 in RA disease includes understanding the specific role of CCL-18 at different stages of RA and its interactions with other cytokines, chemokines, and immune cells. This will help to clarify the potential value of CCL-18 in estimating the duration of RA. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of CCL-18 detection should be improved to more accurately reflect changes in CCL-18 levels in RA patients, thus providing more reliable data for estimating disease duration [].

Although there is currently no direct method to estimate RA duration through CCL-18 levels, comprehensive analysis of CCL-18 with other related factors and long-term longitudinal follow-up studies can offer new insights and evidence to assess the disease course of RA [].

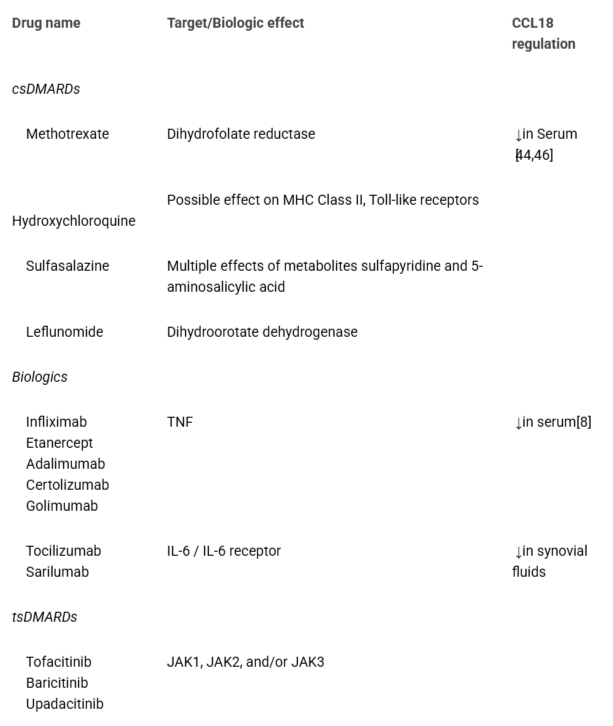

There are several approved medicines for rheumatoid arthritis treatments. These treatments are usually divided into three groups: targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs), conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs), or Biologics. csDMARD includes Methotrexate, Hydroxychloroquine, Sulfasalazine and Leflunomide. And tsDMARD includes tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib, which all target/inhibit Janus kinase 1 (JAK1, a most important JAK for RA to regular IL-6 – STAT signaling pathway) while biologics mostly target TNF (such as Infliximab, Etanercept, Adalimumab, Certolizumab, Golimumab) and IL-6 receptor (such as Tocilizumab and Sarilumab). CCL18 is believed to induce IL-6 production. So far, there is no drug is directly targets CCL18 for RA treatment. Moreover, only a few drugs report decreased CCL18 levels either in serum or synovial fluid such as Tocilizumab and Methotrexate [,]. Table 1 summarizes the currently approved RA treatment drug with its associated report of CCL18 regulation [,,].

Increasing shreds of evidence indicate that CCL18 plays a critical role in RA pathogenesis and correlates with disease activity. Elevated CCL18 has been reported in many cases in either circulating serum or synovial fluids or both. However, most approved RA treatment drugs serve as upstream regulators of CCL18 directly or indirectly, instead of directly targeting CCL18 or its receptor (PITPNM3). Even though the exact principle of CCL18-RA regulation remains unknown, the current preliminary data and setting indicate the feasibility of CCL18 to serve as a drug target for RA treatment. Even currently no FDA-approved CCL18-based method for RA development measure, disease duration, or disease activities, CCL18 showed great potential to be one of the clinical biomarkers, as it shows a highly positive correlation to the RA disease pathogenies. More and more evidence supports the view of CCL18 in RA pathogenesis, such as critical roles in multiple signal pathways and relation among other RA-associated cytokines. Turning CCL18 into clinical approaches still needs further research and studies, but it is feasible to be used combined with other current clinical approaches as a measurement parameter for RA development.

Van Raemdonck K, Umar S, Shahrara S. The pathogenic importance of CCL21 and CCR7 in rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020 Oct;55:86-93. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.05.007. Epub 2020 May 18. PMID: 32499193; PMCID: PMC10018533.

Yang YL, Li XF, Song B, Wu S, Wu YY, Huang C, Li J. The role of CCL3 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2023 Aug;10(4):793-808. doi: 10.1007/s40744-023-00554-0. Epub 2023 May 25. PMID: 37227653; PMCID: PMC10326236.

Zhang F, Wei K, Slowikowski K, Fonseka CY, Rao DA, Kelly S, Goodman SM, Tabechian D, Hughes LB, et al. Defining inflammatory cell states in rheumatoid arthritis joint synovial tissues by integrating single-cell transcriptomics and mass cytometry. Nat Immunol. 2019 Jul;20(7):928-942. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0378-1. Epub 2019 May 6. PMID: 31061532; PMCID: PMC6602051.

Kishimoto T, Kang S. IL-6 revisited: From rheumatoid arthritis to CAR T cell therapy and COVID-19. Annu Rev Immunol. 2022 Apr 26;40:323-348. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101220-023458. Epub 2022 Feb 3. PMID: 35113729.

Radstake TR, van der Voort R, ten Brummelhuis M, de Waal Malefijt M, Looman M, Figdor CG, van den Berg WB, Barrera P, Adema GJ. Increased expression of CCL18, CCL19, and CCL17 by dendritic cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and regulation by Fc gamma receptors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Mar;64(3):359-67. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.017566. Epub 2004 Aug 26. PMID: 15331393; PMCID: PMC1755402.

Mo YQ, Zhang GC, Jing J, Ma JD, Dai L. P058 Chemokine CCL18 enriched in synovial fluid is involved in joint destruction through promoting migration of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(Suppl 1):A25-A25. Available from: https://ard.bmj.com/content/78/Suppl_1/A25.2

Schutyser E, Struyf S, Wuyts A, Put W, Geboes K, Grillet B, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J. Selective induction of CCL18/PARC by staphylococcal enterotoxins in mononuclear cells and enhanced levels in septic and rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2001 Dec;31(12):3755-62. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200112)31:12<3755::aid-immu3755>3.0.co;2-o. PMID: 11745396.

van Lieshout AW, Fransen J, Flendrie M, Eijsbouts AM, van den Hoogen FH, van Riel PL, Radstake TR. Circulating levels of the chemokine CCL18 but not CXCL16 are elevated and correlate with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Oct;66(10):1334-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066084. Epub 2007 Mar 9. PMID: 17350968; PMCID: PMC1994323.

Hieshima K, Imai T, Baba M, Shoudai K, Ishizuka K, Nakagawa T, Tsuruta J, Takeya M, Sakaki Y, Takatsuki K, Miura R, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Yoshie O, Nomiyama H. A novel human CC chemokine PARC that is most homologous to macrophage-inflammatory protein-1 alpha/LD78 alpha and chemotactic for T lymphocytes, but not for monocytes. J Immunol. 1997 Aug 1;159(3):1140-9. PMID: 9233607.

Politz O, Kodelja V, Guillot P, Orfanos CE, Goerdt S. Pseudoexons and regulatory elements in the genomic sequence of the beta-chemokine, alternative macrophage activation-associated CC-chemokine (AMAC)-1. Cytokine. 2000 Feb;12(2):120-6. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0538. PMID: 10671296.

Tasaki Y, Fukuda S, Iio M, Miura R, Imai T, Sugano S, Yoshie O, Hughes AL, Nomiyama H. Chemokine PARC gene (SCYA18) generated by fusion of two MIP-1alpha/LD78alpha-like genes. Genomics. 1999 Feb 1;55(3):353-7. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5670. PMID: 10049593.

Li HY, Cui XY, Wu W, Yu FY, Yao HR, Liu Q, Song EW, Chen JQ. Pyk2 and Src mediate signaling to CCL18-induced breast cancer metastasis. J Cell Biochem. 2014 Mar;115(3):596-603. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24697. PMID: 24142406.

Chen J, Yao Y, Gong C, Yu F, Su S, Chen J, Liu B, Deng H, Wang F, Lin L, Yao H, Su F, Anderson KS, Liu Q, Ewen ME, Yao X, Song E. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis via PITPNM3. Cancer Cell. 2011 Apr 12;19(4):541-55. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.006. Erratum in: Cancer Cell. 2011 Jun 14;19(6):814-6. PMID: 21481794; PMCID: PMC3107500.

Bystrom J, Clanchy FI, Taher TE, Al-Bogami MM, Muhammad HA, Alzabin S, Mangat P, Jawad AS, Williams RO, Mageed RA. Response to treatment with TNFα inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with high levels of GM-CSF and GM-CSF+ T lymphocytes. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017 Oct;53(2):265-276. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8610-y. PMID: 28488248; PMCID: PMC5597702.

Murayama MA, Shimizu J, Miyabe C, Yudo K, Miyabe Y. Chemokines and chemokine receptors as promising targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2023 Feb 13;14:1100869. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1100869. PMID: 36860872; PMCID: PMC9968812.

Auer J, Bläss M, Schulze-Koops H, Russwurm S, Nagel T, Kalden JR, Röllinghoff M, Beuscher HU. Expression and regulation of CCL18 in synovial fluid neutrophils of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(5):R94. doi: 10.1186/ar2294. PMID: 17875202; PMCID: PMC2212580.

Takayasu A, Miyabe Y, Yokoyama W, Kaneko K, Fukuda S, Miyasaka N, Miyabe C, Kubota T, Nanki T. CCL18 activates fibroblast-like synoviocytes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013 Jun;40(6):1026-8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121412. PMID: 23728190.

Li XF, Chen X, Bao J, Xu L, Zhang L, Huang C, Meng XM, Li J. PTEN negatively regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in adjuvant-induced arthritis. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019 Dec;47(1):3687-3696. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1661849. PMID: 31842626.

Li XF, Jing J, Ma JD, Deng C, Chen LF, Zheng DH, Dai L, et al. PTEN methylation promotes inflammation and activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:700373. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.700373.

Tan Y, Yuebin, PITPMN3 is a potential gene therapy target to treat rheumatoid arthritis in fibroblast-like synoviocytes by inhibiting CCL18-associated effect, which might activate Toll-like receptor pathway. Mol Ther. 2021;29(4):368-368.

Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The immunology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Immunol. 2021 Jan;22(1):10-18. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00816-x.

Mo YQ, Jing J, Ma JD, Deng C, Chen LF, Zheng DH, et al. SAT0048 Overexpression of CCL18 promotes migration and activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:681. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-eular.5384.

Moadab F, Khorramdelazad H, Abbasifard M. Role of CCL2/CCR2 axis in the immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: Latest evidence and therapeutic approaches. Life Sci. 2021 Mar 15;269:119034. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119034. Epub 2021 Jan 13. PMID: 33453247.

Haringman JJ, Gerlag DM, Smeets TJ, Baeten D, van den Bosch F, Bresnihan B, Breedveld FC, Dinant HJ, Legay F, Gram H, Loetscher P, Schmouder R, Woodworth T, Tak PP. A randomized controlled trial with an anti-CCL2 (anti-monocyte chemotactic protein 1) monoclonal antibody in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Aug;54(8):2387-92. doi: 10.1002/art.21975. PMID: 16869001.

Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Kato D, Kaneko Y, Terada W. Association between matrix metalloprotease-3 levels and radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A post hoc analysis from a Japanese Phase 3 clinical trial of peficitinib (RAJ4). Mod Rheumatol. 2024 Aug 20;34(5):947-953. doi: 10.1093/mr/road102. PMID: 37902304.

Zhu M, Ding Q, Lin Z, Fu R, Zhang F, Li Z, Zhang M, Zhu Y. New Targets and Strategies for Rheumatoid Arthritis: From Signal Transduction to Epigenetic Aspect. Biomolecules. 2023 Apr 28;13(5):766. doi: 10.3390/biom13050766. PMID: 37238636; PMCID: PMC10216079.

Zeng W, Xiong L, Wu W, Li S, Liu J, Yang L, Lao L, Huang P, Zhang M, Chen H, Miao N, Lin Z, Liu Z, Yang X, Wang J, Wang P, Song E, Yao Y, Nie Y, Chen J, Huang D. CCL18 signaling from tumor-associated macrophages activates fibroblasts to adopt a chemoresistance-inducing phenotype. Oncogene. 2023 Jan;42(3):224-237. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02540-2. Epub 2022 Nov 22. PMID: 36418470; PMCID: PMC9836934.

Ding Q, Hu W, Wang R, Yang Q, Zhu M, Li M, Cai J, Rose P, Mao J, Zhu YZ. Signaling pathways in rheumatoid arthritis: implications for targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Feb 17;8(1):68. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01331-9. PMID: 36797236; PMCID: PMC9935929.

Lin YP, Su CC, Huang JY, Lin HC, Cheng YJ, Liu MF, Yang BC. Aberrant integrin activation induces p38 MAPK phosphorylation resulting in suppressed Fas-mediated apoptosis in T cells: implications for rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Immunol. 2009 Oct;46(16):3328-35. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.07.021. Epub 2009 Aug 20. PMID: 19698994.

Thalhamer T, McGrath MA, Harnett MM. MAPKs and their relevance to arthritis and inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 Apr;47(4):409-14. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem297. Epub 2008 Jan 10. PMID: 18187523.

Yasuta Y, Kaminaka R, Nagai S, Mouri S, Ishida K, Tanaka A, Zhou Y, Sakurai H, Yokoyama S. Cooperative function of oncogenic MAPK signaling and the loss of Pten for melanoma migration through the formation of lamellipodia. Sci Rep. 2024 Jan 17;14(1):1525. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-52020-8. PMID: 38233537; PMCID: PMC10794247.

Zhou P, Meng X, Nie Z, Wang H, Wang K, Du A, Lei Y. PTEN: an emerging target in rheumatoid arthritis? Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Apr 26;22(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01618-6. PMID: 38671436; PMCID: PMC11046879.

He X, Chen X, Zhang H, Xie T, Ye XY. Selective Tyk2 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents: a patent review (2015-2018). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2019 Feb;29(2):137-149. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1567713. Epub 2019 Jan 22. PMID: 30621465.

Monari C, Bevilacqua S, Piccioni M, Pericolini E, Perito S, Calvitti M, Bistoni F, Kozel TR, Vecchiarelli A. A microbial polysaccharide reduces the severity of rheumatoid arthritis by influencing Th17 differentiation and proinflammatory cytokines production. J Immunol. 2009 Jul 1;183(1):191-200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804144. PMID: 19542430.

Stump KL, Lu LD, Dobrzanski P, Serdikoff C, Gingrich DE, Dugan BJ, Angeles TS, Albom MS, Ator MA, Dorsey BD, Ruggeri BA, Seavey MM. A highly selective, orally active inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, CEP-33779, ablates disease in two mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011 Apr 21;13(2):R68. doi: 10.1186/ar3329. PMID: 21510883; PMCID: PMC3132063.

Vomero M, Caliste M, Barbati C, Speziali M, Celia AI, Ucci F, Ciancarella C, Putro E, Colasanti T, Buoncuore G, Corsiero E, Bombardieri M, Spinelli FR, Ceccarelli F, Conti F, Alessandri C. Tofacitinib Decreases Autophagy of Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes From Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Mar 3;13:852802. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.852802. PMID: 35308233; PMCID: PMC8928732.

Gotthardt D, Trifinopoulos J, Sexl V, Putz EM. JAK/STAT Cytokine Signaling at the Crossroad of NK Cell Development and Maturation. Front Immunol. 2019 Nov 12;10:2590. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02590. PMID: 31781102; PMCID: PMC6861185.

Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. "Do We Know Jack" About JAK? A Closer Look at JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00287.

Zhao T, Hu Z, Berry G, Frye R, Bernstein K, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, et al. Abstract 12924: CCL18 Promotes Effector Functions of Pro-Inflammatory Macrophages by Inactivating GSK-3β. Circulation. 2021;144(Suppl 1):A12924-A12924.

Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Sep;69(9):1580-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461. Erratum in: Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Oct;69(10):1892. PMID: 20699241.

Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Miyasaka N, Mukai M, Matsubara T, et al. Adalimumab, a human anti-TNF monoclonal antibody, outcome study for the prevention of joint damage in Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: the HOPEFUL 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Mar;73(3):536-43. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202433. Epub 2013 Jan 11. PMID: 23316080; PMCID: PMC4151516.

Rubbert-Roth A, Aletaha D, Devenport J, Sidiropoulos PN, Luder Y, Edwardes MD, Jacobs JWG. Effect of disease duration and other characteristics on efficacy outcomes in clinical trials of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Feb 1;60(2):682-691. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa259. PMID: 32844216; PMCID: PMC7850526.

Ducreux J, Durez P, Galant C, Nzeusseu Toukap A, Van den Eynde B, Houssiau FA, Lauwerys BR. Global molecular effects of tocilizumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Jan;66(1):15-23. doi: 10.1002/art.38202. PMID: 24449571.

Al-Hashimi NH, Al-Hashimi AMA, Alosami MH. Evaluation of the Human Pulmonary Activation-Regulated Chemokine (CCL18/PARC) and Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Levels in Iraqi Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. The Iraqi Journal of Science. 2020;61(4):pp. 108-113.

Tsaltskan V, Firestein GS. Targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022 Dec;67:102304. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102304. Epub 2022 Oct 10. PMID: 36228471; PMCID: PMC9942784.

Kollert F, Binder M, Probst C, Uhl M, Zirlik A, Kayser G, Voll RE, Peter HH, Zissel G, Prasse A, Warnatz K. CCL18 — potential biomarker of fibroinflammatory activity in chronic periaortitis. J Rheumatol. 2012 Jul;39(7):1407-12. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111143. Epub 2012 May 15. PMID: 22589264.

Tan Y, Han N, Wu X. The Role of CCL18 in Rheumatoid Arthritis Diseases. IgMin Res. January 17, 2025; 3(1): 021-026. IgMin ID: igmin280; DOI:10.61927/igmin280; Available at: igmin.link/p280

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20007, United States

2Faculty of Education, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

3Department of Nutrition, Clifford Hospital, Guangzhou 510000, China

Address Correspondence:

Yuebin Tan, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology, Georgetown University, Washington, DC 20007, United States, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Tan Y, Han N, Wu X. The Role of CCL18 in Rheumatoid Arthritis Diseases. IgMin Res. January 17, 2025; 3(1): 021-026. IgMin ID: igmin280; DOI:10.61927/igmin280; Available at: igmin.link/p280

Copyright: © 2025 Tan Y, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Figure 1: Scheme for the role of CCL18 in rheumatoid arthrit...

Figure 1: Scheme for the role of CCL18 in rheumatoid arthrit...

Figure 2: Scheme for CCL18 relation to other downstream cyto...

Figure 2: Scheme for CCL18 relation to other downstream cyto...

Table 1: Summary of current approved drugs for RA treatment...

Table 1: Summary of current approved drugs for RA treatment...

Van Raemdonck K, Umar S, Shahrara S. The pathogenic importance of CCL21 and CCR7 in rheumatoid arthritis. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020 Oct;55:86-93. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.05.007. Epub 2020 May 18. PMID: 32499193; PMCID: PMC10018533.

Yang YL, Li XF, Song B, Wu S, Wu YY, Huang C, Li J. The role of CCL3 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2023 Aug;10(4):793-808. doi: 10.1007/s40744-023-00554-0. Epub 2023 May 25. PMID: 37227653; PMCID: PMC10326236.

Zhang F, Wei K, Slowikowski K, Fonseka CY, Rao DA, Kelly S, Goodman SM, Tabechian D, Hughes LB, et al. Defining inflammatory cell states in rheumatoid arthritis joint synovial tissues by integrating single-cell transcriptomics and mass cytometry. Nat Immunol. 2019 Jul;20(7):928-942. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0378-1. Epub 2019 May 6. PMID: 31061532; PMCID: PMC6602051.

Kishimoto T, Kang S. IL-6 revisited: From rheumatoid arthritis to CAR T cell therapy and COVID-19. Annu Rev Immunol. 2022 Apr 26;40:323-348. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101220-023458. Epub 2022 Feb 3. PMID: 35113729.

Radstake TR, van der Voort R, ten Brummelhuis M, de Waal Malefijt M, Looman M, Figdor CG, van den Berg WB, Barrera P, Adema GJ. Increased expression of CCL18, CCL19, and CCL17 by dendritic cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and regulation by Fc gamma receptors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005 Mar;64(3):359-67. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.017566. Epub 2004 Aug 26. PMID: 15331393; PMCID: PMC1755402.

Mo YQ, Zhang GC, Jing J, Ma JD, Dai L. P058 Chemokine CCL18 enriched in synovial fluid is involved in joint destruction through promoting migration of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(Suppl 1):A25-A25. Available from: https://ard.bmj.com/content/78/Suppl_1/A25.2

Schutyser E, Struyf S, Wuyts A, Put W, Geboes K, Grillet B, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J. Selective induction of CCL18/PARC by staphylococcal enterotoxins in mononuclear cells and enhanced levels in septic and rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 2001 Dec;31(12):3755-62. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200112)31:12<3755::aid-immu3755>3.0.co;2-o. PMID: 11745396.

van Lieshout AW, Fransen J, Flendrie M, Eijsbouts AM, van den Hoogen FH, van Riel PL, Radstake TR. Circulating levels of the chemokine CCL18 but not CXCL16 are elevated and correlate with disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Oct;66(10):1334-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.066084. Epub 2007 Mar 9. PMID: 17350968; PMCID: PMC1994323.

Hieshima K, Imai T, Baba M, Shoudai K, Ishizuka K, Nakagawa T, Tsuruta J, Takeya M, Sakaki Y, Takatsuki K, Miura R, Opdenakker G, Van Damme J, Yoshie O, Nomiyama H. A novel human CC chemokine PARC that is most homologous to macrophage-inflammatory protein-1 alpha/LD78 alpha and chemotactic for T lymphocytes, but not for monocytes. J Immunol. 1997 Aug 1;159(3):1140-9. PMID: 9233607.

Politz O, Kodelja V, Guillot P, Orfanos CE, Goerdt S. Pseudoexons and regulatory elements in the genomic sequence of the beta-chemokine, alternative macrophage activation-associated CC-chemokine (AMAC)-1. Cytokine. 2000 Feb;12(2):120-6. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0538. PMID: 10671296.

Tasaki Y, Fukuda S, Iio M, Miura R, Imai T, Sugano S, Yoshie O, Hughes AL, Nomiyama H. Chemokine PARC gene (SCYA18) generated by fusion of two MIP-1alpha/LD78alpha-like genes. Genomics. 1999 Feb 1;55(3):353-7. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5670. PMID: 10049593.

Li HY, Cui XY, Wu W, Yu FY, Yao HR, Liu Q, Song EW, Chen JQ. Pyk2 and Src mediate signaling to CCL18-induced breast cancer metastasis. J Cell Biochem. 2014 Mar;115(3):596-603. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24697. PMID: 24142406.

Chen J, Yao Y, Gong C, Yu F, Su S, Chen J, Liu B, Deng H, Wang F, Lin L, Yao H, Su F, Anderson KS, Liu Q, Ewen ME, Yao X, Song E. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis via PITPNM3. Cancer Cell. 2011 Apr 12;19(4):541-55. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.006. Erratum in: Cancer Cell. 2011 Jun 14;19(6):814-6. PMID: 21481794; PMCID: PMC3107500.

Bystrom J, Clanchy FI, Taher TE, Al-Bogami MM, Muhammad HA, Alzabin S, Mangat P, Jawad AS, Williams RO, Mageed RA. Response to treatment with TNFα inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with high levels of GM-CSF and GM-CSF+ T lymphocytes. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017 Oct;53(2):265-276. doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8610-y. PMID: 28488248; PMCID: PMC5597702.

Murayama MA, Shimizu J, Miyabe C, Yudo K, Miyabe Y. Chemokines and chemokine receptors as promising targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2023 Feb 13;14:1100869. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1100869. PMID: 36860872; PMCID: PMC9968812.

Auer J, Bläss M, Schulze-Koops H, Russwurm S, Nagel T, Kalden JR, Röllinghoff M, Beuscher HU. Expression and regulation of CCL18 in synovial fluid neutrophils of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(5):R94. doi: 10.1186/ar2294. PMID: 17875202; PMCID: PMC2212580.

Takayasu A, Miyabe Y, Yokoyama W, Kaneko K, Fukuda S, Miyasaka N, Miyabe C, Kubota T, Nanki T. CCL18 activates fibroblast-like synoviocytes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013 Jun;40(6):1026-8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121412. PMID: 23728190.

Li XF, Chen X, Bao J, Xu L, Zhang L, Huang C, Meng XM, Li J. PTEN negatively regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in adjuvant-induced arthritis. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019 Dec;47(1):3687-3696. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2019.1661849. PMID: 31842626.

Li XF, Jing J, Ma JD, Deng C, Chen LF, Zheng DH, Dai L, et al. PTEN methylation promotes inflammation and activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:700373. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.700373.

Tan Y, Yuebin, PITPMN3 is a potential gene therapy target to treat rheumatoid arthritis in fibroblast-like synoviocytes by inhibiting CCL18-associated effect, which might activate Toll-like receptor pathway. Mol Ther. 2021;29(4):368-368.

Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. The immunology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Immunol. 2021 Jan;22(1):10-18. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00816-x.

Mo YQ, Jing J, Ma JD, Deng C, Chen LF, Zheng DH, et al. SAT0048 Overexpression of CCL18 promotes migration and activation of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:681. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-eular.5384.

Moadab F, Khorramdelazad H, Abbasifard M. Role of CCL2/CCR2 axis in the immunopathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis: Latest evidence and therapeutic approaches. Life Sci. 2021 Mar 15;269:119034. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119034. Epub 2021 Jan 13. PMID: 33453247.

Haringman JJ, Gerlag DM, Smeets TJ, Baeten D, van den Bosch F, Bresnihan B, Breedveld FC, Dinant HJ, Legay F, Gram H, Loetscher P, Schmouder R, Woodworth T, Tak PP. A randomized controlled trial with an anti-CCL2 (anti-monocyte chemotactic protein 1) monoclonal antibody in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Aug;54(8):2387-92. doi: 10.1002/art.21975. PMID: 16869001.

Takeuchi T, Tanaka Y, Morita Y, Kato D, Kaneko Y, Terada W. Association between matrix metalloprotease-3 levels and radiographic progression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A post hoc analysis from a Japanese Phase 3 clinical trial of peficitinib (RAJ4). Mod Rheumatol. 2024 Aug 20;34(5):947-953. doi: 10.1093/mr/road102. PMID: 37902304.

Zhu M, Ding Q, Lin Z, Fu R, Zhang F, Li Z, Zhang M, Zhu Y. New Targets and Strategies for Rheumatoid Arthritis: From Signal Transduction to Epigenetic Aspect. Biomolecules. 2023 Apr 28;13(5):766. doi: 10.3390/biom13050766. PMID: 37238636; PMCID: PMC10216079.

Zeng W, Xiong L, Wu W, Li S, Liu J, Yang L, Lao L, Huang P, Zhang M, Chen H, Miao N, Lin Z, Liu Z, Yang X, Wang J, Wang P, Song E, Yao Y, Nie Y, Chen J, Huang D. CCL18 signaling from tumor-associated macrophages activates fibroblasts to adopt a chemoresistance-inducing phenotype. Oncogene. 2023 Jan;42(3):224-237. doi: 10.1038/s41388-022-02540-2. Epub 2022 Nov 22. PMID: 36418470; PMCID: PMC9836934.

Ding Q, Hu W, Wang R, Yang Q, Zhu M, Li M, Cai J, Rose P, Mao J, Zhu YZ. Signaling pathways in rheumatoid arthritis: implications for targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Feb 17;8(1):68. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01331-9. PMID: 36797236; PMCID: PMC9935929.

Lin YP, Su CC, Huang JY, Lin HC, Cheng YJ, Liu MF, Yang BC. Aberrant integrin activation induces p38 MAPK phosphorylation resulting in suppressed Fas-mediated apoptosis in T cells: implications for rheumatoid arthritis. Mol Immunol. 2009 Oct;46(16):3328-35. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.07.021. Epub 2009 Aug 20. PMID: 19698994.

Thalhamer T, McGrath MA, Harnett MM. MAPKs and their relevance to arthritis and inflammation. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008 Apr;47(4):409-14. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem297. Epub 2008 Jan 10. PMID: 18187523.

Yasuta Y, Kaminaka R, Nagai S, Mouri S, Ishida K, Tanaka A, Zhou Y, Sakurai H, Yokoyama S. Cooperative function of oncogenic MAPK signaling and the loss of Pten for melanoma migration through the formation of lamellipodia. Sci Rep. 2024 Jan 17;14(1):1525. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-52020-8. PMID: 38233537; PMCID: PMC10794247.

Zhou P, Meng X, Nie Z, Wang H, Wang K, Du A, Lei Y. PTEN: an emerging target in rheumatoid arthritis? Cell Commun Signal. 2024 Apr 26;22(1):246. doi: 10.1186/s12964-024-01618-6. PMID: 38671436; PMCID: PMC11046879.

He X, Chen X, Zhang H, Xie T, Ye XY. Selective Tyk2 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents: a patent review (2015-2018). Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2019 Feb;29(2):137-149. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1567713. Epub 2019 Jan 22. PMID: 30621465.

Monari C, Bevilacqua S, Piccioni M, Pericolini E, Perito S, Calvitti M, Bistoni F, Kozel TR, Vecchiarelli A. A microbial polysaccharide reduces the severity of rheumatoid arthritis by influencing Th17 differentiation and proinflammatory cytokines production. J Immunol. 2009 Jul 1;183(1):191-200. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804144. PMID: 19542430.

Stump KL, Lu LD, Dobrzanski P, Serdikoff C, Gingrich DE, Dugan BJ, Angeles TS, Albom MS, Ator MA, Dorsey BD, Ruggeri BA, Seavey MM. A highly selective, orally active inhibitor of Janus kinase 2, CEP-33779, ablates disease in two mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011 Apr 21;13(2):R68. doi: 10.1186/ar3329. PMID: 21510883; PMCID: PMC3132063.

Vomero M, Caliste M, Barbati C, Speziali M, Celia AI, Ucci F, Ciancarella C, Putro E, Colasanti T, Buoncuore G, Corsiero E, Bombardieri M, Spinelli FR, Ceccarelli F, Conti F, Alessandri C. Tofacitinib Decreases Autophagy of Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes From Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Front Pharmacol. 2022 Mar 3;13:852802. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.852802. PMID: 35308233; PMCID: PMC8928732.

Gotthardt D, Trifinopoulos J, Sexl V, Putz EM. JAK/STAT Cytokine Signaling at the Crossroad of NK Cell Development and Maturation. Front Immunol. 2019 Nov 12;10:2590. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02590. PMID: 31781102; PMCID: PMC6861185.

Bousoik E, Montazeri Aliabadi H. "Do We Know Jack" About JAK? A Closer Look at JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway. Front Oncol. 2018;8:287. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00287.

Zhao T, Hu Z, Berry G, Frye R, Bernstein K, Goronzy JJ, Weyand CM, et al. Abstract 12924: CCL18 Promotes Effector Functions of Pro-Inflammatory Macrophages by Inactivating GSK-3β. Circulation. 2021;144(Suppl 1):A12924-A12924.

Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO 3rd, Birnbaum NS, Burmester GR, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Sep;69(9):1580-8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461. Erratum in: Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Oct;69(10):1892. PMID: 20699241.

Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N, Miyasaka N, Mukai M, Matsubara T, et al. Adalimumab, a human anti-TNF monoclonal antibody, outcome study for the prevention of joint damage in Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: the HOPEFUL 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Mar;73(3):536-43. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202433. Epub 2013 Jan 11. PMID: 23316080; PMCID: PMC4151516.

Rubbert-Roth A, Aletaha D, Devenport J, Sidiropoulos PN, Luder Y, Edwardes MD, Jacobs JWG. Effect of disease duration and other characteristics on efficacy outcomes in clinical trials of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Feb 1;60(2):682-691. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa259. PMID: 32844216; PMCID: PMC7850526.

Ducreux J, Durez P, Galant C, Nzeusseu Toukap A, Van den Eynde B, Houssiau FA, Lauwerys BR. Global molecular effects of tocilizumab therapy in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Jan;66(1):15-23. doi: 10.1002/art.38202. PMID: 24449571.

Al-Hashimi NH, Al-Hashimi AMA, Alosami MH. Evaluation of the Human Pulmonary Activation-Regulated Chemokine (CCL18/PARC) and Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Levels in Iraqi Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. The Iraqi Journal of Science. 2020;61(4):pp. 108-113.

Tsaltskan V, Firestein GS. Targeting fibroblast-like synoviocytes in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2022 Dec;67:102304. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2022.102304. Epub 2022 Oct 10. PMID: 36228471; PMCID: PMC9942784.

Kollert F, Binder M, Probst C, Uhl M, Zirlik A, Kayser G, Voll RE, Peter HH, Zissel G, Prasse A, Warnatz K. CCL18 — potential biomarker of fibroinflammatory activity in chronic periaortitis. J Rheumatol. 2012 Jul;39(7):1407-12. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111143. Epub 2012 May 15. PMID: 22589264.