Communication Training at Medical School: A Quantitative Analysis

Clinical Medicine Public Health受け取った 09 Oct 2024 受け入れられた 25 Oct 2024 オンラインで公開された 28 Oct 2024

Focusing on Biology, Medicine and Engineering ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Previous Full Text

An Open Letter to the 2022 Winners of the Nobel Prize in Physics

受け取った 09 Oct 2024 受け入れられた 25 Oct 2024 オンラインで公開された 28 Oct 2024

Background: There is an increasing focus on communication between doctors and patients, and recent systematic reviews argue that teaching doctors necessary communication skills benefits patients at large. Moreover, patients report the lack of communication as their second-leading complaint. Motivational interviewing has proved to be person-centered in healthcare in communication between patients and doctors.

Aim: To examine how being inspired by motivational interviewing theory and using the Calgary Cambridge guide could improve medical students' communication skills at the master level using a mixed-method approach.

Methods: A cohort study with an exposed cohort compared to a non-exposed historical cohort.

The participants were students in their sixth year of medical training from the Clinical Department of the University of Southern Denmark.

The non-exposed cohort received laboratory training based on the Calgary Cambridge Guide. After this training, they participated in a two-month clinical "stay" and recorded two digital audio files of a real conversation with a patient about delivering information. The exposed cohort followed the same schedule but received additional special training in MI. All audio files were analyzed using the Motivational Interviewing Integrity method (MITI).

An additional focus group interview was conducted to support the results.

Results: Medical students demonstrated improvements in several essential areas of their communication style favorable to the MI approach, particularly empathy, and person-centeredness. The focus group interviews supported these findings.

There is an increasing focus on communication between doctors and patients. Two recent systematic reviews argue that it benefits the patients that doctors receive the necessary communication skills. Moreover, the lack of communication reports is the second-largest complaint from patients [-]. From a medical point-of-view, the discussion is that low communication competencies may lead to patients referring to their symptoms but not getting into details. Lack of communication may lead to the doctor underestimating the illness level, affecting the patient’s feelings []. Doctors must have excellent communication skills; therefore, efficient training and the ability to measure the effect of such efforts have been called for [].

Patients prefer to be met by healthcare professionals, including doctors, with respect, recognition, and open conversation [,,]. Doctors must move from a paternalistic communication practice to more emphatic, collaborative behavior and be aware that patients' experiences are essential in the treatment and care []. Further, doctors must combine all relevant information to get suggestions for clinical tests and treatment, give information effectively, motivate the patient, and make them feel as safe as possible [,]. Universities worldwide provide communication training to medical students; method descriptions on evidence-based courses may be available []. Such can be based on the Calgary Cambridge Guide (CCG), which presents an overarching platform for evidence-based medical communication [,]. The CCG guide helps the doctor track the patient's conversation. Other similar concepts are available, including training in showing the patients` compassion and respect and using tools to aid communication and handle the clinical setting. An example could be accommodating the patient's disorders [-] or delivering a clear message [].

Motivational interviewing is helpful in healthcare for communicating complex messages, such as motivation for behavioral change in patients with various health problems, such as substance abuse, obesity, smoking, and diabetes. It can be used in shared decision-making with the patient and to support medical interventions [-]. MI is recommended in the psychiatric clinic for its gentle approach to vulnerable patients in their treatment and care [].

It has been proved that more randomized controlled trials have presented the Motivational Interviewing (MI) approach, which has made it possible to develop a respectful, supportive, acknowledging, and professional relationship with the patients [-]. Motivational Interviewing [] is a patient-centered, directive counseling approach that strives to develop the patient's intrinsic motivation to change. The approach targeted behaviors through simultaneous strategic evocation and strengthening of change talk (i.e., self-statements that support change), skillful handling, and reducing patient resistance to change. The approach emphasizes reflective listening, open questioning, collaboration, support of patients' autonomy and self-efficacy, and appropriate elicitation of change talk. These characteristics embody the spirit or style in which the professional communicator interacts with their patients as they help them develop their awareness and eventually commit to behavior change. The effect of MI is measured by coding and counting (MITI) [].

Although the Calgary Cambridge Guide is a recognized and evidence-based theory used in communication training at medical schools [], the CCG does not guide the factual communication technique, dialogue, or the first encounter. It also does not prescribe a way to measure an immediate effect. The MI technique and the CCG supplement each other and present an evidence-based intervention that can be measured [].

To examine how being inspired by motivational interviewing theory and using the Calgary Cambridge guide could improve medical students' communication skills at the master level using a mixed-method approach.

A cohort study was conducted with an exposed cohort compared to a non-exposed historical cohort.

Further, as a closure of the study, all participant groups in the exposed cohort participated in a semi-structured focus group interview for each group (on average, with 5-6 students in each) to explore their experience of participating in the study.

The students were recruited by their lecturers in class, and participants for the focus group interview were recruited through the medical student’s Facebook group.

Each student uploaded the audio files in both the historical and the exposed groups to a secure system at the University, to which the researcher CLL had access only. The MITI coding was conducted in the system, and the data was stored securely according to the data agreement for the University of Southern Denmark.

The focus group interviews were uploaded securely in the secure system at the University of Southern Denmark database and transcribed using NVivo and by the researcher CLL only.

The participants were students in the 6th year of medical training at The University of Southern Denmark. The medical students had received their first mandatory medical communication training before this study in their third year of medical school. In our research, the students participated in their compulsory second communication training course. Most students were Danish who had completed their university bachelor's degree in medicine after the third year. There were also students of Norwegian and Swedish origins who had completed their bachelor's degree at another European medical school, e.g., in Poland, Hungary, or Czechoslovakia.

A total of 190 students participated in the study - 94 (n = 94) students in the non-exposed cohort and 100 (n = 100) students in the exposed cohort. In the non-exposed group, 47 (n = 47) female and 43 (n = 43) male students, aged between 21 and 36, were present. In the exposed group, 53 (n = 53) female and 47 (n = 47) male students, aged between 22 and 33, were present. All the students spoke and understood Danish.

The inclusion criteria were that the students had completed their bachelor’s degree in medicine at a university where they had received basic theory or training in patient-centered communication. They also had to be able to understand and speak Danish.

The exclusion criteria were students who had enrolled in medical training at the bachelor level but had not received communication training and had not mastered the Danish language.

The inclusion criteria for the focus group interviews were students who had participated in the MI training and submission of audio files.

Traditionally, medical students receive training on communication skills with patients, e.g., to forward diagnoses and treatments related to their medical illnesses. Further, medical students receive communication skills training on the ward with colleagues.

The CCG guides this training and focuses on developing patient-centered interviewing and promoting or fostering skills. This guide by Silverman, Kurtz, and Draper [] was designed to align competent doctor-patient communication skills and provide an evidence-based structure for their analysis and teaching. The CCG guide is widely used in communication training programs at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels []. Moreover, the students are trained to elicit patients' views of their problems and concerns and encourage patients to participate in medical decision-making. The training sessions consisted of 5 x 3 hours, where the first session was theoretical, catching up on medical communication. A didactic approach was used. The following four sessions involved a professional actor cast to play patients in different situations. During a session, four students play the role of a doctor. Afterward, the role play is evaluated by the student playing the doctor, the other students, the actor, and finally, the trainer has the closing remarks. To create a relaxed atmosphere where the students feel safe, the groups never exceed 10 participants.

After the initial five communication lectures, our students' cohorts did clinical studies on the ward, including training in communicating with patients, relatives, and other healthcare professionals. Before the closure of their clinical period, they were to digital record two interviews with patients, containing at least 10 minutes of communication where the medical student gave the patient information about the patient's situation. Further, they had to write a page reflecting on good and bad communication experienced in the clinic. The audio files were uploaded to a secure university server where the first author (CLL) could access them. Another 3x3 hours were scheduled to listen to each student’s recording, give feedback, and follow up on experiences from the clinic.

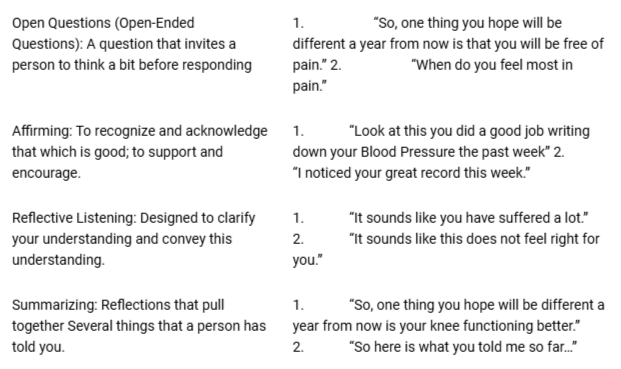

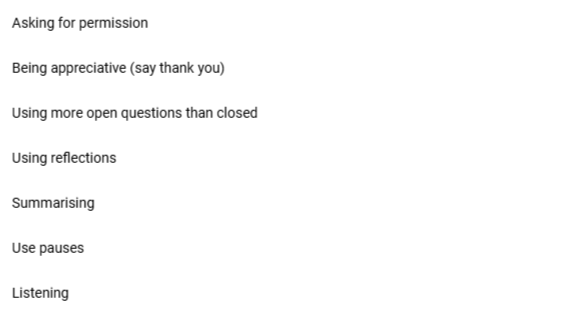

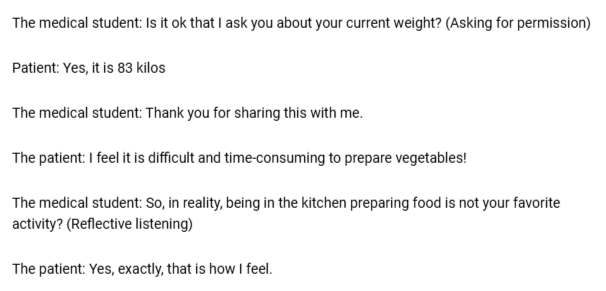

In addition to the CCG set-up in the historical cohort, we incorporated communication training using the MI approach developed by Rollnick et al. []. The training course was 5 X 3 hours. A deductive pedagogic approach was used [], and a brief motivational interview guide [], which makes the MI appropriate for use in healthcare settings by doctors and other healthcare professionals, was used []. In this approach, a conversation takes between 5 and 15 minutes to carry out. It involves establishing rapport between the doctor and patient using open questions, reflections, and summaries to understand their health concerns, relate to behavioral difficulties, and elicit how to help the patient. First, we presented and trained to ask open questions (O), affirming (A), reflections (R), and summarising (S) (OARS) (Tables 1-3). We intensified the approach by focusing on 1) the start of the conversation, 2) asking permission when asking delicate topics, 3) thanking the patient for sharing private information, and 4) pausing to let the patient speak. The students needed to be taught the difference between kinds of reflection due to the duration of the training.

In the analytical work with the sound files, we were inspired by Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity coding (MITI) []. MITI is a behavioral coding that indicates how well or poorly an individual uses motivational interviewing. The MITI coding should have been done over a sound file of 20 minutes, but we adjusted and used it on the 10-minute sound files. Our MITI-inspired coding registered MI behavior: the number of open questions versus closed questions, the ratio of summarising and using reflections, pauses, and encouraging `mums` and `hers`. In the coding, we did not differ between simple and complex reflections.

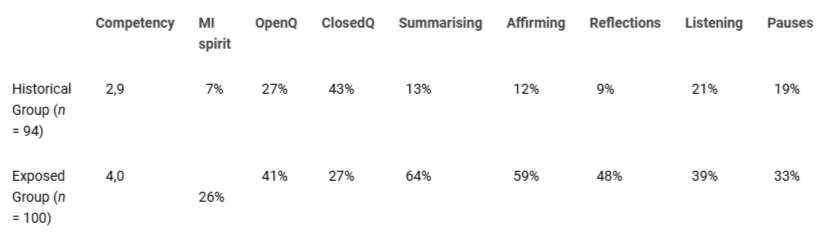

Using a global rating score [], the recommended scores for achievement of proficiency (expected after the training) and competency (expected of the students who are more familiar with using MI after training) are 3.5 and 4.0, respectively []. Global scores are marked on a five-point Likert Scale [], with the coder assuming a beginning score of '3 ' and deviating up or down [].

The data were tabulated and analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test in STATA Statistical Software (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). This was applied to compare pre-test and post-test scores from the MITI coding. Here, a p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

For the exposed group four Focus group interviews were conducted in the sixth year of medical school after the training, recording of audio files, and MITI coding. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed inspired by Braun and Clarke []. This part of the project is described in an additional article.

The following results present the data from the MITI coding of the sound files. Hereafter, we present short excerpts from the focus group interviews, the full versions of which will be presented in an additional paper.

We had 94 (n = 94) participants in the historical cohort from 1.1.2015 to 31.12.2017 and 100 (n = 100) participants in the exposed cohort from 1.1 2017 to 31.12.2019. All sound files had a duration of 10-12 minutes. According to the MITI scores, the historical group reached 2.9 on the Likert Scale, whereas the exposed group reached 4.0. This proves that the historical group is below proficiency level for communicating according to the MITI coding, which is 3.5. According to the MITI, the historical group is reaching a competency level of 4.0. The results demonstrated that the exposed cohort had a higher rating in favor of using motivational communication skills in their communication skills than the historical group. On average, the students in the exposed group had more open questions than closed and used reflective listening language; they summarised, asked for permission, thanked the patient for sharing information, and listened using pauses to let the patient speak or think. In the historical group, the students were between 2.5 and 3.0 at the MITI coding on MI spirit. The low scores were primarily due to the need to build relationships with the patients through open questions, reflections, and summarising. Overall, the MI spirit did not reach the proficiency level of the historical group. The exposed group had a higher frequency of using the MI theory, e.g. making encouraging sounds or words like hmmm, I see, yes, or, I understand during the communication with patients. This became evident during the recording when they were listening. According to the MITI coding, this means that the MI spirit has improved, and the students are communicating more emphatically with their patients and at a competency level (Table 4).

Results from the focus group interviews

Combining our study with qualitative research added another dimension to our study.

Generally, all medical students interviewed in the focus groups from the group conveyed that motivational interviewing helped them become more structured in their communication skills, using the Calgary Cambridge guide as a frame.

However, the students anticipated challenges. The interviews' analysis identified one overall theme and four sub-themes.

Overall theme: Motivational interviewing gives you a tool to communicate with patients

All the medical students (n = 4 groups, 28 students) interviewed stated that MI is a valuable and straightforward technique that enables patient-centered communication.

During the interviews, four sub-themes emerged, and all sub-themes were chosen according to how the students explained their experiences with their communication using MI: 1) Training using the MI in the class is necessary 2) Using the MI to open the conversation, establish rapport and summerise what is said 3) A need for follow up in the clinic with feedback from tutors on communication with patients in situ 4) Supervision in class and feedback from lecturer and peers.

The following is an excerpt of quotations from the focus group interviews.

A male student in the exposed group said:

“I found out that starting the conversation with an open question and letting the patient speak made my conversation much more structured while also using the CCG. Of course, I used a closed question, but I knew when to do it.”

They found that following the steps and using the Calgary Cambridge Guide helped them become more confident communicating with the patients.

“Asking for permission is a great tool to gain the patient’s trust. It makes such a difference how they accept me as a medical student and not a qualified doctor.”

In particular, summarising both the doctor and the patient made it easier to follow a plan during the encounter with the patient.

A female student expressed:

“Summarising gives both the patient and me a chance to be on track. Where are we, and what was said?”.

A female student followed:

“I needed feedback on how I used my communication skills in the clinic. We received feedback from the class and the lecturer when training with actors. In the clinic, you get uncertain if you do it correctly. “

Our study compared an exposed group of medical students taught communication inspired by motivational interviewing (MI) with a historical group who received regular communication training. In general, the medical students in our exposed cohort communicated to a higher degree with a patient-centered approach [,,]. The results of the scores after the MITI coding point towards communication skills with empathetic communication skills empathy and to a more significant extent than the historical cohort. This is an important finding, as empathy amongst healthcare professionals are core component of healthcare [,,].

Communication skills are essential for training emphatic doctors. Hence, the question is not whether we should build communication training in medical schools but how much training is needed and what the training should contain [].

We found that the medical students developed what we refer to as the MI spirit [] by implementing an MI-inspired approach []. This is understood that the students, in cooperation with the patient, use the CCG guide; they use more open questions than closed ones and use reflections frequently during the communication instead of asking closed questions to the patient. Patients in general find the doctor more empathetic when using open questions and reflections during the communication []. The MI spirit rate captures the degree to which the medical students support the patient's autonomy, evoke the patients for change, and support a collaborative communication environment [,].

In our exposed cohort, we trained the students in the Calgary Cambridge Guide (CCG) which is the framework where motivational interviewing is the communication technique []. Thus we cannot see how the (CCG) was used from the scores the focus group interviews indicated that the students felt they understood how to use the CCG and the MI communication technique together and thus the communication became more structured with a proper start and closure of the communication with the patient. A scoping review by Lei et al. supports our findings [].

In the study, we further found that the present training course, consisting of 3 hours of theory followed by 4 x 3 hours of skills communication training with actors, enables the students to acquire skills in patient communication at the proficiency level [].

Implementing evidence-based curricula with the content of a didactic approach with theory on communication techniques, frequently incorporated skills training and exercises facilitated by lecturers who are training in communication skills themselves and have clinical experience will heighten the level of communication for medical students []. Further, an educational approach where feedback is part of the training. Peer feedback from the lecturer may enhance communication skills encompassing empathy and compassion []. In the focus group, receiving feedback was mentioned both in the skills training and in the students’ clinic at the hospital.

However, several MI assessment points must be present to achieve complete empathetic communication skills measured with an MI approach. As a reference point, the Cambridge Calgary Guide is the communication frame, allowing the student to concentrate on the communication itself. Using the MITI coding system, the validity between the highest scores was autonomy and empathy []. A recent review by Kaltman and Tankersley emphasizes that training must be planned to achieve this [].

Using the MI technique (OARS, Table 1), the student builds a rapport with the patient earlier during the communication, thus creating an opportunity to forward the information to the patient []. When the students use OARS, they communicate with empathy and compassion, which correlates with increased patient well-being and quality of life [].

The healthcare system in Western countries aims to have short hospital stays and accelerated discharge from the hospital, continuing the care and treatment in the patient's own homes []. It is essential that the communication and guidance about the patient's discharge and the further plan are clear and concise and that the patient understands the plan and feels safe [,]. Our study showed that the students could establish rapport, build trust with patients, and experiment with face-to-face medical communication with patients and relatives. In general, the students in the exposed group encompassed the theory of MI. In particular, they demonstrated skills in using reflective listening by reflecting on the patients' words and thus enabled the patient to feel "that the doctor knows how I feel." Others before us have found that communication inspired by MI can enhance the communication between healthcare persons and patients [].

The findings from the focus group interviews pointed out that the students in the exposed group felt motivated to use the MI approach in the clinic and found the CCG more manageable. Keifenheim et al. support this and investigate the approach of sixth-semester medical students to MI. The results showed that basic MI skills can be taught successfully [].

Hospitals have implemented mandatory communication courses for healthcare professionals, using the Cambridge Calgary guide and patient-centered communication [,]. However, the training has not been evaluated as the MITI scoring in this article.

Empathy skills can be measured in coding systems [,], making this approach more valid for teaching and measuring them [,].

When comparing the results from the MITI coding and the results from the focus group interviews we conclude that simple communication techniques may change the students` awareness of their position and the patient's perspective [,]. This awareness may lead to a higher intent for being curious with empathetic compassionate person-centered communication in their treatment and care []. The medical students have limited clinical experience, but this immediate training enables the students to achieve basic communication skills and a base to continue communication training after graduating. In Southern Denmark, mandatory communication courses for intern doctors are held during the first two years of practice, enabling the students to continue their communication skills [,].

Our study has limitations. As this is a large cohort group, some students still need to complete the training course, which did not count in the overall assessment.

The sound files were 10 minutes, not a full 20-minute recording as recommended for the MITI coding. This may have to be considered when comparing this study to other settings. However, it has been demonstrated that presenting communication skills over a short period of five minutes is sufficient for evaluating communication skills [].

Further, we did not follow the complete MITI coding manual, which required that the students be taught how to use complex reflections. In MI training, complex reflection requires mastering MI communication skills at a high level and extended training in communicating in clinical practice with patients. This did not comply with our students in the sixth year of medical school. Adding complex reflection to post-graduate training for doctors may be relevant as the doctors here often work with complex patient cases []. Further, we did not note if the participants were male or female, which may have been interesting to evaluate if there is a gender difference in learning and using MI.

Our study included medical students at the University of Southern Denmark, and our findings may not apply to other medical schools in Denmark or faculties abroad.

Despite these limitations, the main strengths are a large cohort study. We used valid and reliable coding techniques by qualified coders and achieved an acceptable overall level of inter-rater reliability. Further, a qualitative approach was used to support the quantitative findings.

This study indicates that teaching practical and theoretical knowledge of MI as part of a mandatory training course in the 6th semester improved communication skills in medical students with minimal clinical experience after 15 hours of MI-inspired training. However, it is noted that by exploring the overall experience in focus group interviews, the students did question how they could be competent using the MI training in their clinic without follow-up, feedback, and mentoring. Further research should assess the long-term benefits of this training and its impact on the patient experience and doctor-patient communication. Implementing blended learning modules such as short videos and podcasts to support in-class lectures in MI may also improve the learning style of medical students.

The local ethics committee approved the study (No. S-20222000 – 103). All participants gave informed consent to participate.

The authors thank all the medical students who participated in the study. We also acknowledge MSc Fred Ericks for proofreading and MSc C Grupe for statistical assistance.

Contributor CLL was the PI and guarantor of this project, wrote the protocol, conducted all the interviews, and analyzed and was the PI throughout the research project and the article submission. MT participated in the analysis and writing of this article.

Funding the authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Skär L, Söderberg S. Patients' complaints regarding healthcare encounters and communication. Nurs Open. 2018 Feb 26;5(2):224-232. doi: 10.1002/nop2.132. PMID: 29599998; PMCID: PMC5867282.

Haroutunian P, Alsabri M, Kerdiles FJ, Adel Ahmed Abdullah H, Bellou A. Analysis of Factors and Medical Errors Involved in Patient Complaints in a European Emergency Department. Adv J Emerg Med. 2017 Dec 11;2(1):e4. doi: 10.22114/AJEM.v0i0.34. PMID: 31172067; PMCID: PMC6548105.

Riedl D, Schüßler G. The Influence of Doctor-Patient Communication on Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2017 Jun;63(2):131-150. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2017.63.2.131. PMID: 28585507.

Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J. Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014 Aug;23(8):678-89. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437. Epub 2014 May 29. PMID: 24876289; PMCID: PMC4112446.

Stanley DE, Sehon SR. Medical reasoning and doctor-patient communication. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019 Dec;25(6):962-969. doi: 10.1111/jep.13235. Epub 2019 Jul 16. PMID: 31309663.

Ruben BD. Communication Theory and Health Communication Practice: The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same. Health Commun. 2016;31(1):1-11. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.923086. Epub 2014 Nov 3. PMID: 25365726.

Thygesen MK, Fuglsang M, Miiller MM. Factors affecting patients' ratings of health-care satisfaction. Dan Med J. 2015 Oct;62(10):A5150. PMID: 26441393.

Lindhardt CL, Rubak S, Mogensen O, Hansen HP, Goldstein H, Lamont RF, Joergensen JS. Healthcare professionals experience with motivational interviewing in their encounter with obese pregnant women. Midwifery. 2015 Jul;31(7):678-84. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.010. Epub 2015 Apr 8. PMID: 25931276.

Graf J, Smolka R, Simoes E, Zipfel S, Junne F, Holderried F, Wosnik A, Doherty AM, Menzel K, Herrmann-Werner A. Communication skills of medical students during the OSCE: Gender-specific differences in a longitudinal trend study. BMC Med Educ. 2017 May 2;17(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0913-4. PMID: 28464857; PMCID: PMC5414383.

Matthews MG, Van Wyk JM. Exploring a communication curriculum through a focus on social accountability: A case study at a South African medical school. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018 May 28;10(1):e1-e10. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1634. PMID: 29943599; PMCID: PMC6018691.

Silverman J, Kurtz SM, Draper J, van Dalen J, Platt FW. Skills for communicating with patients: Radcliffe Pub. Oxford, UK; 2005.

Hess R, Hagemeier NE, Blackwelder R, Rose D, Ansari N, Branham T. Teaching Communication Skills to Medical and Pharmacy Students Through a Blended Learning Course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016 May 25;80(4):64. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80464. PMID: 27293231; PMCID: PMC4891862.

Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, Kubota K, Katsumata N, Uchitomi Y. Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jul 10;32(20):2166-72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2756. Epub 2014 Jun 9. PMID: 24912901.

Aiarzaguena JM, Grandes G, Gaminde I, Salazar A, Sánchez A, Ariño J. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a psychosocial and communication intervention carried out by GPs for patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychol Med. 2007 Feb;37(2):283-94. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009536. Epub 2006 Dec 13. PMID: 17164029.

Rollnick S, Butler CC, McCambridge J, Kinnersley P, Elwyn G, Resnicow K. Consultations about changing behaviour. BMJ. 2005 Oct 22;331(7522):961-3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.961. PMID: 16239696; PMCID: PMC1261200.

Bischof G, Bischof A, Rumpf HJ. Motivational Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Approach for Use in Medical Practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021 Feb 19;118(7):109-115. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0014. PMID: 33835006; PMCID: PMC8200683.

Vallentin-Holbech L, Karsberg SH, Nielsen AS, Feldstein Ewing SW, Rømer Thomsen K. Preliminary evaluation of a novel group-based motivational interviewing intervention with adolescents: a feasibility study. Front Public Health. 2024 Mar 6;12:1344286. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1344286. PMID: 38510360; PMCID: PMC10951374.

Lindhardt CL, Rubak S, Mogensen O, Hansen HP, Lamont RF, Jørgensen JS. Training in motivational interviewing in obstetrics: a quantitative analytical tool. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014 Jul;93(7):698-704. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12401. Epub 2014 May 24. PMID: 24773133.

Boom SM, Oberink R, Zonneveld AJE, van Dijk N, Visser MRM. Implementation of motivational interviewing in the general practice setting: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care. 2022 Jan 28;23(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01623-z. PMID: 35172737; PMCID: PMC8800318.

Correll CU. Using Patient-Centered Assessment in Schizophrenia Care: Defining Recovery and Discussing Concerns and Preferences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 14;81(3):MS19053BR2C. doi: 10.4088/JCP.MS19053BR2C. PMID: 32297720.

Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior: Guilford Press; 2008.

Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J, Miller W, Ernst D. Revised global scales: Motivational interviewing treatment integrity 3.1. 1 (MITI 3.1. 1). Unpublished manuscript Albuquerque: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions, University of New Mexico. 2010.

Kurtz S, Draper J, Silverman J. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. 2nd ed. London 2017; 388.

Illeris K. Læring: Samfundslitteratur; 2015.

Miller RW, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. Helping People Change,: Guilford Press; 2012.

Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002.

Allen IE, Seaman CA. Likert scales and data analyses. Quality Progress. 2007;40(7):64-5.

Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing Int J Transgend Health. 2022 Oct 25;24(1):1-6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597. PMID: 36713144; PMCID: PMC9879167.

Ammentorp J, Bigi S, Silverman J, Sator M, Gillen P, Ryan W, Rosenbaum M, Chiswell M, Doherty E, Martin P. Upscaling communication skills training - lessons learned from international initiatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Feb;104(2):352-359. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.028. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32888756.

Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, Lyna P, Coffman CJ, Dolor RJ, Gulbrandsen P, Ostbye T. Physician empathy and listening: associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011 Nov-Dec;24(6):665-72. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.110025. PMID: 22086809; PMCID: PMC3363295.

Kisely S, Wyder M, Dietrich J, Robinson G, Siskind D, Crompton D. Motivational aftercare planning to better care: Applying the principles of advanced directives and motivational interviewing to discharge planning for people with mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2017 Feb;26(1):41-48. doi: 10.1111/inm.12261. Epub 2016 Sep 28. PMID: 27681041.

Lei LYC, Chew KS, Chai CS, Chen YY. Evidence for motivational interviewing in educational settings among medical schools: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Aug 8;24(1):856. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05845-w. PMID: 39118104; PMCID: PMC11312404.

Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, Roberts MB, Kilgannon H, Trzeciak S, Roberts BW. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019 Aug 22;14(8):e0221412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221412. PMID: 31437225; PMCID: PMC6705835.

Kaltman S, Tankersley A. Teaching Motivational Interviewing to Medical Students: A Systematic Review. Acad Med. 2020 Mar;95(3):458-469. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003011. PMID: 31577585.

Novack TA, Kurowicki J, Issa K, Pierce TP, Festa A, McInerney VK, Scillia AJ. Accelerated Discharge following Total Knee Arthroplasty May Be Safe in a Teaching Institution. J Knee Surg. 2020 Jan;33(1):8-11. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676066. Epub 2018 Nov 30. PMID: 30500972.

Wolderslund M, Kofoed PE, Ammentorp J. The effectiveness of a person-centred communication skills training programme for the health care professionals of a large hospital in Denmark. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Jun;104(6):1423-1430. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.018. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33303282.

Zachariae R, O'Connor M, Lassesen B, Olesen M, Kjær LB, Thygesen M, Mørcke AM. The self-efficacy in patient-centeredness questionnaire - a new measure of medical student and physician confidence in exhibiting patient-centered behaviors. BMC Med Educ. 2015 Sep 15;15:150. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0427-x. Erratum in: BMC Med Educ. 2015 Oct 08;15:170. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0454-7. PMID: 26374729; PMCID: PMC4572680.

Keifenheim KE, Velten-Schurian K, Fahse B, Erschens R, Loda T, Wiesner L, Zipfel S, Herrmann-Werner A. "A change would do you good": Training medical students in Motivational Interviewing using a blended-learning approach - A pilot evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2019 Apr;102(4):663-669. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.027. Epub 2018 Nov 1. PMID: 30448043.

Ammentorp J, Graugaard LT, Lau ME, Andersen TP, Waidtløw K, Kofoed PE. Mandatory communication training of all employees with patient contact. Patient Educ Couns. 2014 Jun;95(3):429-32. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.005. Epub 2014 Mar 12. PMID: 24666773.

Ammentorp J, Bigi S, Silverman J, Sator M, Gillen P, Ryan W, Rosenbaum M, Chiswell M, Doherty E, Martin P. Upscaling communication skills training - lessons learned from international initiatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Feb;104(2):352-359. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.028. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32888756.

Iversen ED, Wolderslund MO, Kofoed PE, Gulbrandsen P, Poulsen H, Cold S, Ammentorp J. Codebook for rating clinical communication skills based on the Calgary-Cambridge Guide. BMC Med Educ. 2020 May 6;20(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02050-3. PMID: 32375756; PMCID: PMC7201796.

Epstein RM, Beach MC. "I don't need your pills, I need your attention:" Steps toward deep listening in medical encounters. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023 Oct;53:101685. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101685. Epub 2023 Aug 10. PMID: 37659284.

The Region of Southern Denmark. Further Education for Medical Doctors: The Region of Southern Denmark; 2021. Available from: http://www.videreuddannelsen-syd.dk/wm130319.

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011 Mar-Apr;9(2):100-3. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. PMID: 21403134; PMCID: PMC3056855

Lindhardt CH, Thygesen MA. Communication Training at Medical School: A Quantitative Analysis. IgMin Res.. October 28, 2024; 2(10): 862-869. IgMin ID: igmin261; DOI:10.61927/igmin261; Available at: igmin.link/p261

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

1Centre for Research in Patient Communication, Clinical Institute, Department of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, 5000 Odense, Denmark

2Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Odense University Hospital

3Clinical Institute, The Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

4School of Medicine, Faculty of Health, Deakin University, Victoria, Australia

Address Correspondence:

Christina Louise Lindhardt, Centre for Research in Patient Communication, Clinical Institute, Department of Health Sciences, University of Southern Denmark, 5000 Odense, Denmark, Email: [email protected]; [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Lindhardt CH, Thygesen MA. Communication Training at Medical School: A Quantitative Analysis. IgMin Res.. October 28, 2024; 2(10): 862-869. IgMin ID: igmin261; DOI:10.61927/igmin261; Available at: igmin.link/p261

Copyright: © 2024 Lindhardt CL, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Table 1: OARS Components and Examples....

Table 1: OARS Components and Examples....

Table 2: Additional Components which are used in training a...

Table 2: Additional Components which are used in training a...

Table 3: Examples of using MI in training....

Table 3: Examples of using MI in training....

Table 4: A comparison between the historical and exposed gr...

Table 4: A comparison between the historical and exposed gr...

Skär L, Söderberg S. Patients' complaints regarding healthcare encounters and communication. Nurs Open. 2018 Feb 26;5(2):224-232. doi: 10.1002/nop2.132. PMID: 29599998; PMCID: PMC5867282.

Haroutunian P, Alsabri M, Kerdiles FJ, Adel Ahmed Abdullah H, Bellou A. Analysis of Factors and Medical Errors Involved in Patient Complaints in a European Emergency Department. Adv J Emerg Med. 2017 Dec 11;2(1):e4. doi: 10.22114/AJEM.v0i0.34. PMID: 31172067; PMCID: PMC6548105.

Riedl D, Schüßler G. The Influence of Doctor-Patient Communication on Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2017 Jun;63(2):131-150. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2017.63.2.131. PMID: 28585507.

Reader TW, Gillespie A, Roberts J. Patient complaints in healthcare systems: a systematic review and coding taxonomy. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014 Aug;23(8):678-89. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002437. Epub 2014 May 29. PMID: 24876289; PMCID: PMC4112446.

Stanley DE, Sehon SR. Medical reasoning and doctor-patient communication. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019 Dec;25(6):962-969. doi: 10.1111/jep.13235. Epub 2019 Jul 16. PMID: 31309663.

Ruben BD. Communication Theory and Health Communication Practice: The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same. Health Commun. 2016;31(1):1-11. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2014.923086. Epub 2014 Nov 3. PMID: 25365726.

Thygesen MK, Fuglsang M, Miiller MM. Factors affecting patients' ratings of health-care satisfaction. Dan Med J. 2015 Oct;62(10):A5150. PMID: 26441393.

Lindhardt CL, Rubak S, Mogensen O, Hansen HP, Goldstein H, Lamont RF, Joergensen JS. Healthcare professionals experience with motivational interviewing in their encounter with obese pregnant women. Midwifery. 2015 Jul;31(7):678-84. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.010. Epub 2015 Apr 8. PMID: 25931276.

Graf J, Smolka R, Simoes E, Zipfel S, Junne F, Holderried F, Wosnik A, Doherty AM, Menzel K, Herrmann-Werner A. Communication skills of medical students during the OSCE: Gender-specific differences in a longitudinal trend study. BMC Med Educ. 2017 May 2;17(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0913-4. PMID: 28464857; PMCID: PMC5414383.

Matthews MG, Van Wyk JM. Exploring a communication curriculum through a focus on social accountability: A case study at a South African medical school. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018 May 28;10(1):e1-e10. doi: 10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1634. PMID: 29943599; PMCID: PMC6018691.

Silverman J, Kurtz SM, Draper J, van Dalen J, Platt FW. Skills for communicating with patients: Radcliffe Pub. Oxford, UK; 2005.

Hess R, Hagemeier NE, Blackwelder R, Rose D, Ansari N, Branham T. Teaching Communication Skills to Medical and Pharmacy Students Through a Blended Learning Course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016 May 25;80(4):64. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80464. PMID: 27293231; PMCID: PMC4891862.

Fujimori M, Shirai Y, Asai M, Kubota K, Katsumata N, Uchitomi Y. Effect of communication skills training program for oncologists based on patient preferences for communication when receiving bad news: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014 Jul 10;32(20):2166-72. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.2756. Epub 2014 Jun 9. PMID: 24912901.

Aiarzaguena JM, Grandes G, Gaminde I, Salazar A, Sánchez A, Ariño J. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a psychosocial and communication intervention carried out by GPs for patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychol Med. 2007 Feb;37(2):283-94. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009536. Epub 2006 Dec 13. PMID: 17164029.

Rollnick S, Butler CC, McCambridge J, Kinnersley P, Elwyn G, Resnicow K. Consultations about changing behaviour. BMJ. 2005 Oct 22;331(7522):961-3. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7522.961. PMID: 16239696; PMCID: PMC1261200.

Bischof G, Bischof A, Rumpf HJ. Motivational Interviewing: An Evidence-Based Approach for Use in Medical Practice. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2021 Feb 19;118(7):109-115. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.m2021.0014. PMID: 33835006; PMCID: PMC8200683.

Vallentin-Holbech L, Karsberg SH, Nielsen AS, Feldstein Ewing SW, Rømer Thomsen K. Preliminary evaluation of a novel group-based motivational interviewing intervention with adolescents: a feasibility study. Front Public Health. 2024 Mar 6;12:1344286. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2024.1344286. PMID: 38510360; PMCID: PMC10951374.

Lindhardt CL, Rubak S, Mogensen O, Hansen HP, Lamont RF, Jørgensen JS. Training in motivational interviewing in obstetrics: a quantitative analytical tool. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014 Jul;93(7):698-704. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12401. Epub 2014 May 24. PMID: 24773133.

Boom SM, Oberink R, Zonneveld AJE, van Dijk N, Visser MRM. Implementation of motivational interviewing in the general practice setting: a qualitative study. BMC Prim Care. 2022 Jan 28;23(1):21. doi: 10.1186/s12875-022-01623-z. PMID: 35172737; PMCID: PMC8800318.

Correll CU. Using Patient-Centered Assessment in Schizophrenia Care: Defining Recovery and Discussing Concerns and Preferences. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020 Apr 14;81(3):MS19053BR2C. doi: 10.4088/JCP.MS19053BR2C. PMID: 32297720.

Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler C. Motivational interviewing in health care: helping patients change behavior: Guilford Press; 2008.

Moyers T, Martin T, Manuel J, Miller W, Ernst D. Revised global scales: Motivational interviewing treatment integrity 3.1. 1 (MITI 3.1. 1). Unpublished manuscript Albuquerque: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions, University of New Mexico. 2010.

Kurtz S, Draper J, Silverman J. Teaching and Learning Communication Skills in Medicine. 2nd ed. London 2017; 388.

Illeris K. Læring: Samfundslitteratur; 2015.

Miller RW, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. Helping People Change,: Guilford Press; 2012.

Miller W, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002.

Allen IE, Seaman CA. Likert scales and data analyses. Quality Progress. 2007;40(7):64-5.

Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing Int J Transgend Health. 2022 Oct 25;24(1):1-6. doi: 10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597. PMID: 36713144; PMCID: PMC9879167.

Ammentorp J, Bigi S, Silverman J, Sator M, Gillen P, Ryan W, Rosenbaum M, Chiswell M, Doherty E, Martin P. Upscaling communication skills training - lessons learned from international initiatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Feb;104(2):352-359. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.028. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32888756.

Pollak KI, Alexander SC, Tulsky JA, Lyna P, Coffman CJ, Dolor RJ, Gulbrandsen P, Ostbye T. Physician empathy and listening: associations with patient satisfaction and autonomy. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011 Nov-Dec;24(6):665-72. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.110025. PMID: 22086809; PMCID: PMC3363295.

Kisely S, Wyder M, Dietrich J, Robinson G, Siskind D, Crompton D. Motivational aftercare planning to better care: Applying the principles of advanced directives and motivational interviewing to discharge planning for people with mental illness. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2017 Feb;26(1):41-48. doi: 10.1111/inm.12261. Epub 2016 Sep 28. PMID: 27681041.

Lei LYC, Chew KS, Chai CS, Chen YY. Evidence for motivational interviewing in educational settings among medical schools: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. 2024 Aug 8;24(1):856. doi: 10.1186/s12909-024-05845-w. PMID: 39118104; PMCID: PMC11312404.

Patel S, Pelletier-Bui A, Smith S, Roberts MB, Kilgannon H, Trzeciak S, Roberts BW. Curricula for empathy and compassion training in medical education: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019 Aug 22;14(8):e0221412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221412. PMID: 31437225; PMCID: PMC6705835.

Kaltman S, Tankersley A. Teaching Motivational Interviewing to Medical Students: A Systematic Review. Acad Med. 2020 Mar;95(3):458-469. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003011. PMID: 31577585.

Novack TA, Kurowicki J, Issa K, Pierce TP, Festa A, McInerney VK, Scillia AJ. Accelerated Discharge following Total Knee Arthroplasty May Be Safe in a Teaching Institution. J Knee Surg. 2020 Jan;33(1):8-11. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676066. Epub 2018 Nov 30. PMID: 30500972.

Wolderslund M, Kofoed PE, Ammentorp J. The effectiveness of a person-centred communication skills training programme for the health care professionals of a large hospital in Denmark. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Jun;104(6):1423-1430. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.018. Epub 2020 Nov 17. PMID: 33303282.

Zachariae R, O'Connor M, Lassesen B, Olesen M, Kjær LB, Thygesen M, Mørcke AM. The self-efficacy in patient-centeredness questionnaire - a new measure of medical student and physician confidence in exhibiting patient-centered behaviors. BMC Med Educ. 2015 Sep 15;15:150. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0427-x. Erratum in: BMC Med Educ. 2015 Oct 08;15:170. doi: 10.1186/s12909-015-0454-7. PMID: 26374729; PMCID: PMC4572680.

Keifenheim KE, Velten-Schurian K, Fahse B, Erschens R, Loda T, Wiesner L, Zipfel S, Herrmann-Werner A. "A change would do you good": Training medical students in Motivational Interviewing using a blended-learning approach - A pilot evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 2019 Apr;102(4):663-669. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.10.027. Epub 2018 Nov 1. PMID: 30448043.

Ammentorp J, Graugaard LT, Lau ME, Andersen TP, Waidtløw K, Kofoed PE. Mandatory communication training of all employees with patient contact. Patient Educ Couns. 2014 Jun;95(3):429-32. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.005. Epub 2014 Mar 12. PMID: 24666773.

Ammentorp J, Bigi S, Silverman J, Sator M, Gillen P, Ryan W, Rosenbaum M, Chiswell M, Doherty E, Martin P. Upscaling communication skills training - lessons learned from international initiatives. Patient Educ Couns. 2021 Feb;104(2):352-359. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.08.028. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32888756.

Iversen ED, Wolderslund MO, Kofoed PE, Gulbrandsen P, Poulsen H, Cold S, Ammentorp J. Codebook for rating clinical communication skills based on the Calgary-Cambridge Guide. BMC Med Educ. 2020 May 6;20(1):140. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02050-3. PMID: 32375756; PMCID: PMC7201796.

Epstein RM, Beach MC. "I don't need your pills, I need your attention:" Steps toward deep listening in medical encounters. Curr Opin Psychol. 2023 Oct;53:101685. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2023.101685. Epub 2023 Aug 10. PMID: 37659284.

The Region of Southern Denmark. Further Education for Medical Doctors: The Region of Southern Denmark; 2021. Available from: http://www.videreuddannelsen-syd.dk/wm130319.

Epstein RM, Street RL Jr. The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011 Mar-Apr;9(2):100-3. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. PMID: 21403134; PMCID: PMC3056855