Country Risk to Face Global Emergencies: Negative Effects of High Public Debt on Health Expenditures and Fatality Rate in COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis

Public Health Infectious Diseases受け取った 18 Jun 2024 受け入れられた 04 Jul 2024 オンラインで公開された 06 Jul 2024

Focusing on Biology, Medicine and Engineering ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Next Full Text

The Effect of Stacking Sequence and Ply Orientation with Central Hole on Tensile Behavior of Glass Fiber-polyester Composite

受け取った 18 Jun 2024 受け入れられた 04 Jul 2024 オンラインで公開された 06 Jul 2024

Risk is a variation of performance in the presence of events and it can negatively impact socioeconomic system of countries. Statistical evidence here shows that high public debt reduces health expenditures over time and increases the vulnerability and risk of European countries to face health emergencies, such as COVID-19 pandemic crisis. Overall, then, findings suggest that high public debt weakens healthcare and socioeconomic system of countries to cope with crises, such as COVID-19 pandemic, conflicts, natural disasters, etc.

JEL Codes: I18; H12; H51; H60; H63

In contemporary economies, more and more countries have high levels of public debt that force to budget constraints with policies of public finance based on austerity measures (including spending cuts and/or tax increases), which impact funding for health, education and other public sectors [-]. Studies suggest that high levels of public debt may restrict government expenditure, especially in critical sectors like healthcare and education [,]. Moreover, high level of public debt has significative effects on socio-economic system and it can decrease a government’s ability to respond to complex emergencies and social problems [-]. Research paper here explores the relationship between the public debt and healthcare expenditures for assessing country risk, measured with fatality rates, in the presence of pandemic crises, such as COVID-19. Findings can suggest effective long-run policies to face next global emergencies, such as pandemics similar to COVID-19, conflicts, natural disasters, etc., in various countries.

The literature about COVID-19 has a lot of studies on manifold topics [-]. However, how the relationship between the public debt and healthcare expenditures affects fatality rates in the presence of pandemic crises, such as COVID-19, it is hardly known. This study focuses on a group of 27 European nations having comparable socioeconomic systems: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Sweden [].

The study examines variables of the economic and health system in European countries in 2009 and 2019 to assess the level and change before the COVID-19 pandemic crisis and their relationship with case fatality rates of the COVID-19 in 2020 and 2022. Variables under study are:

The average COVID-19 fatality rate in the year 2020, the starting year of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, is used to categorize the sample of European countries under study into two groups:

The arithmetic mean and the change from 2009 to 2019 (ten years) of general government gross debt and of health expenditures in countries of group 1 and 2, with a comparative analysis, assess the evolution of public debt and health expenditures between these categories before the emergence of COVID-19 pandemic crisis. The rate of change ∆ for variable x is given by: x in 2019 minus x in 2009 divided by x in 2009. Statistical analyses are based on descriptive statistics, independent sample T-test to assess the significance of the difference of means between group 1 and 2, correlation analyses of basic relation between health expenditure and COVID-19 fatality rate and a simple regression analysis with log-log model given by the following equation []:

COVID-19 fatality rates 2022

(yi ) = α + β healthcare expenditures per capita 2019 (xi)+ ui []

α = constant

β = coefficient of regression

ui = error term

i (subscript) = countries

Estimated relationship is calculated with Ordinary Last Squares (OLS) method that determines the unknown parameters. Statistical analyses are performed with the IBM SPSS Statistics 26®.

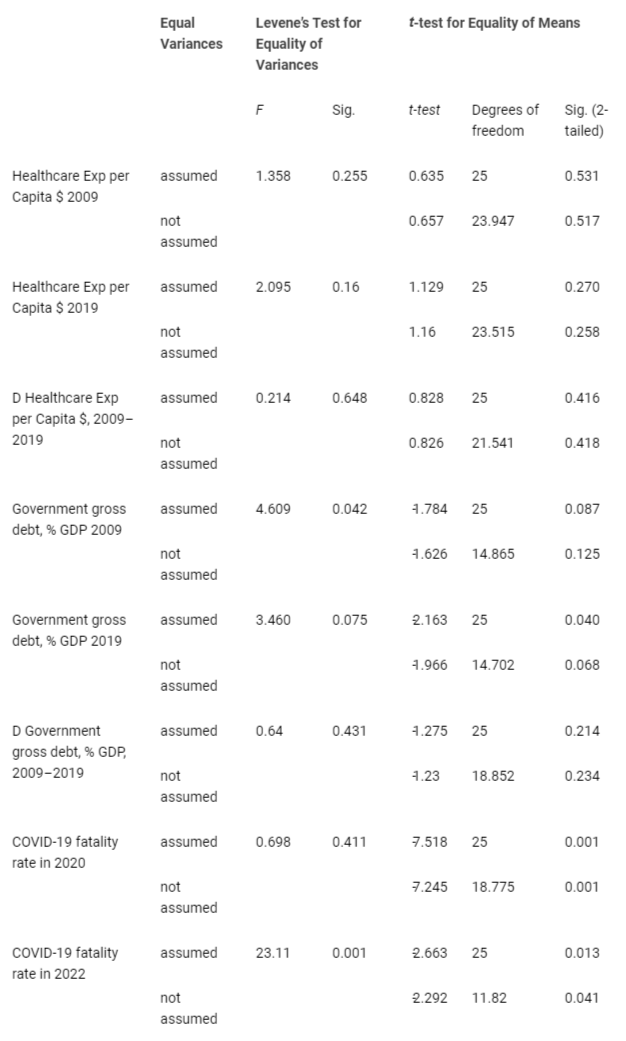

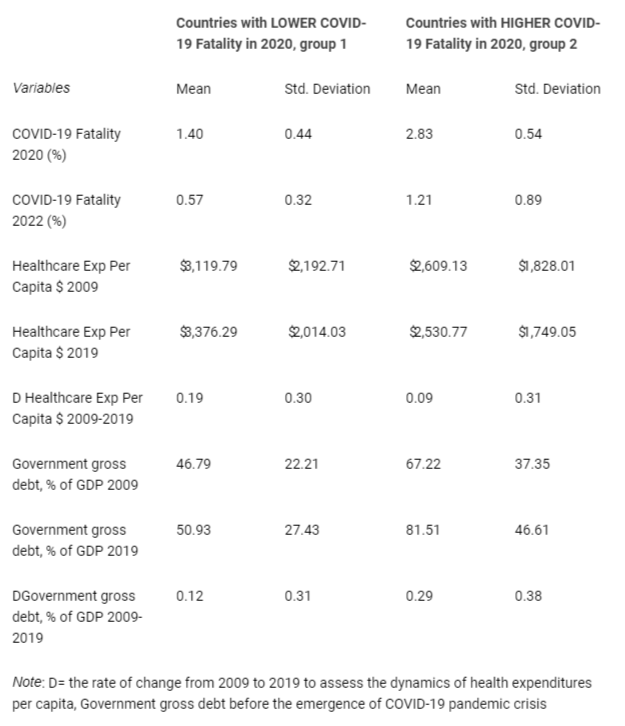

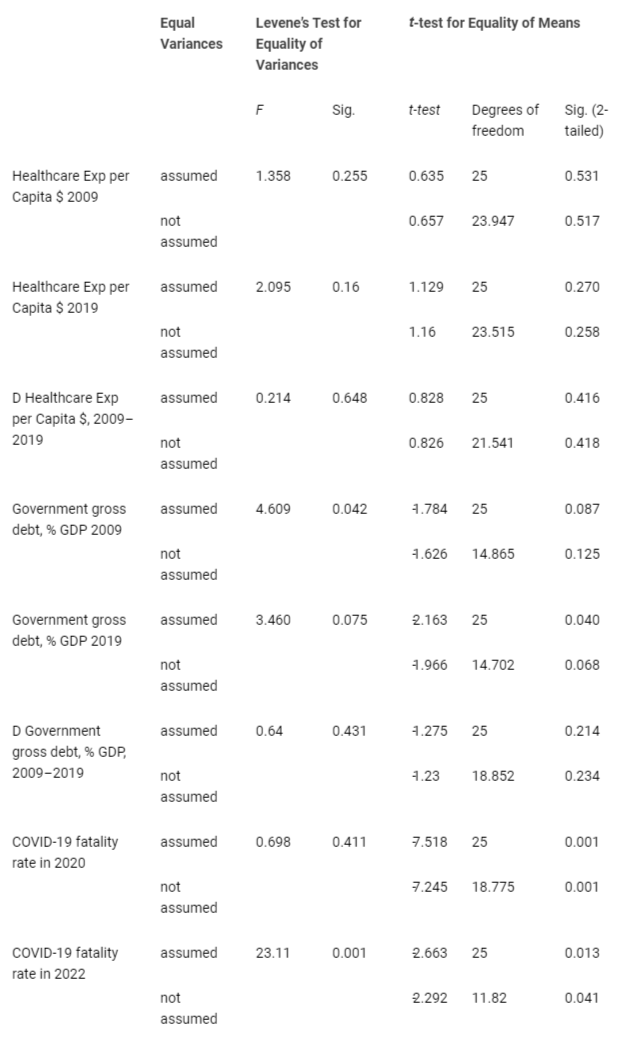

Table 1 reveals that Group 1 with a lower COVID-19 fatality rate in 2020 and 2022 than group 2 has in the year 2009 and 2019 higher levels of health expenditure per capita (> $3,100 per capita). From 2009 to 2019 this group 1 has a rate of growth of health expenditure per capita of 0.19. Instead, countries with a higher COVID-19 fatality rate in 2020 had in 2009 and 2019, levels of health expenditure per capita lower than previous group 1 (about $2,530 in 2009 and $2,600 in 2019). Moreover, this group 2 has a lower rate of growth of health expenditure per capita from 2009 to 2019 and equal to 0.09. If we consider government gross debt as % of GDP, Table 1 reveals that in group 1 is lower both in 2009 (46.8%) and 2019 (50.9%) than group 2, which had 67.2% in 2009 and 81.49% in 2019. In addition, group 1 has from 2009 to 2019 a lower growth of government gross debt (% of GDP) given by 0.12 compared to group 2 that has experienced a high growth of government gross debt (% of GDP) of 0.29, generating a high burden for socioeconomic system, such that public finance had to reduce health expenditures with negatively effects on overall health system. Statistical significance of differences in arithmetic means (Table 1) is verified with independent sample T-test and results are in Table 2: the independent samples T-test compares the means of groups 1 and 2 to determine whether the associated population means are significantly different. Since the p-value is higher than significance level α = 0.05, we can reject the null hypothesis of similarity of arithmetic means between groups 1 and 2, except for the COVID-19 fatality rate in 2020 and 2022.

Table 2: Independent Samples T-Test based on average mean and change of variables from 2009 to 2019 in European countries of group 1 (Countries with LOWER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020) and group 2 (Countries with HIGHER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020).

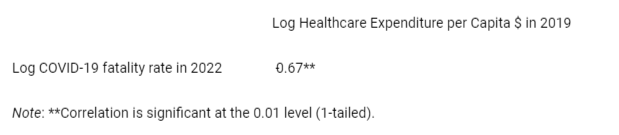

Table 2: Independent Samples T-Test based on average mean and change of variables from 2009 to 2019 in European countries of group 1 (Countries with LOWER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020) and group 2 (Countries with HIGHER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020).Pearson’s coefficient of correlation is −0.67, which indicates a strong negative correlation. The more resources that European nations spend in health sector, the better they are likely to reduce the case fatality rates of COVID-19. The one-tailed significance value – which in this case has p - value < 0.001, considering that the standard alpha value is 0.05, means that correlation analysis here is highly significant (Table 3).

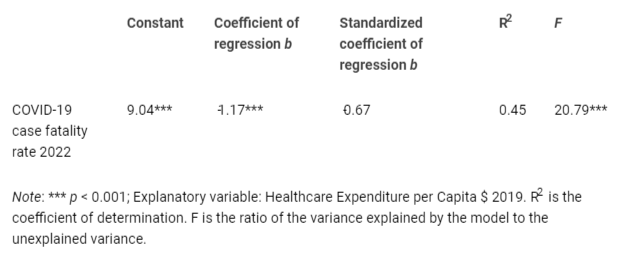

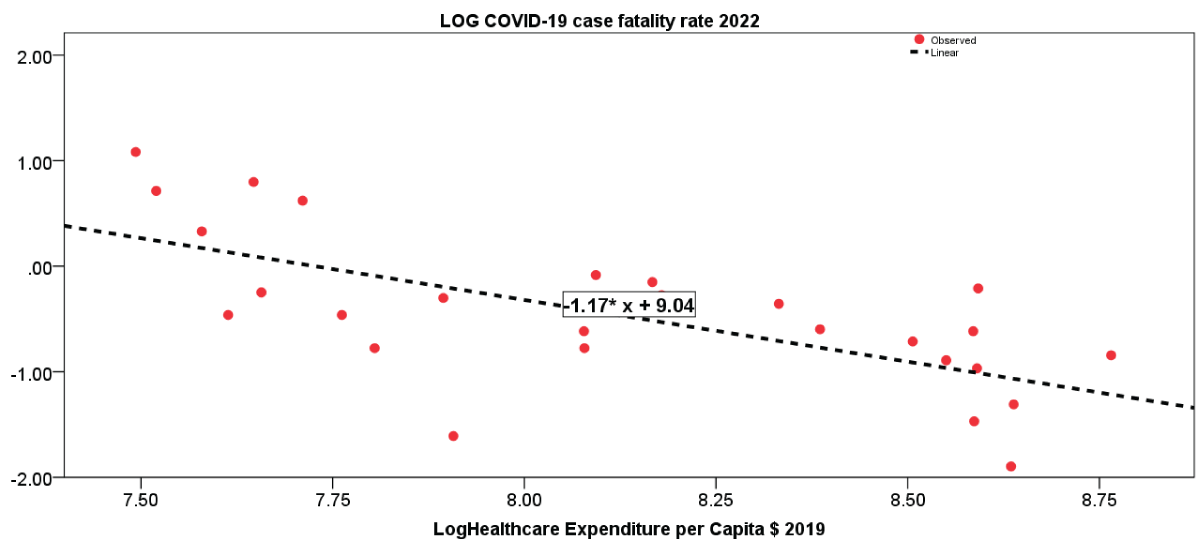

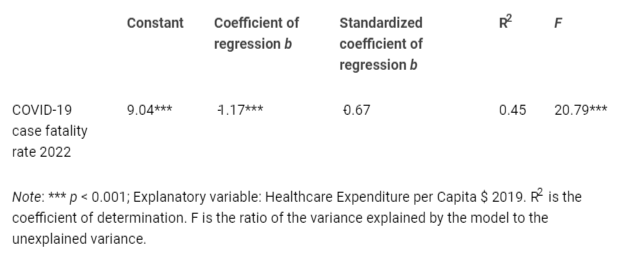

Table 4 presents the results of the regression analysis using the OLS method. The findings clearly indicate that when countries experience a 1% increase in healthcare expenditure per capita in 2019, it leads to a 1.2% reduction in the COVID-19 fatality rate. The R2 coefficient of determination explains approximately 45% of the variance in the data, whereas the F - value is statistically significant (p - value < 0.001), indicating that the independent variable reliably predicts the dependent variable, namely the reduction in the COVID-19 fatality rate.

Table 4: Estimated relationship of COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022 on Healthcare Expenditure per Capita $ 2019, log-log model.

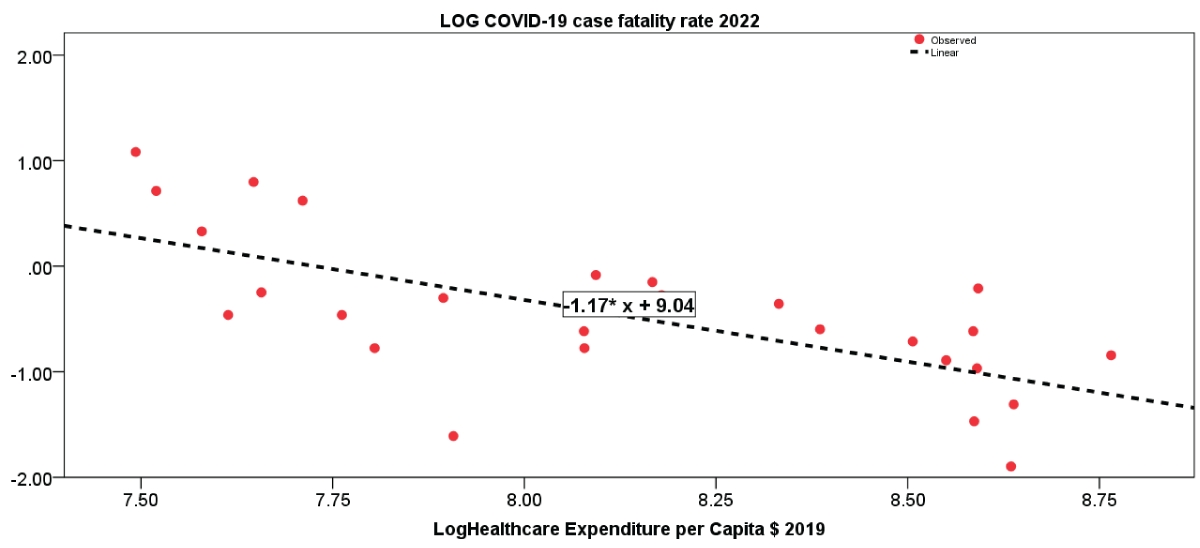

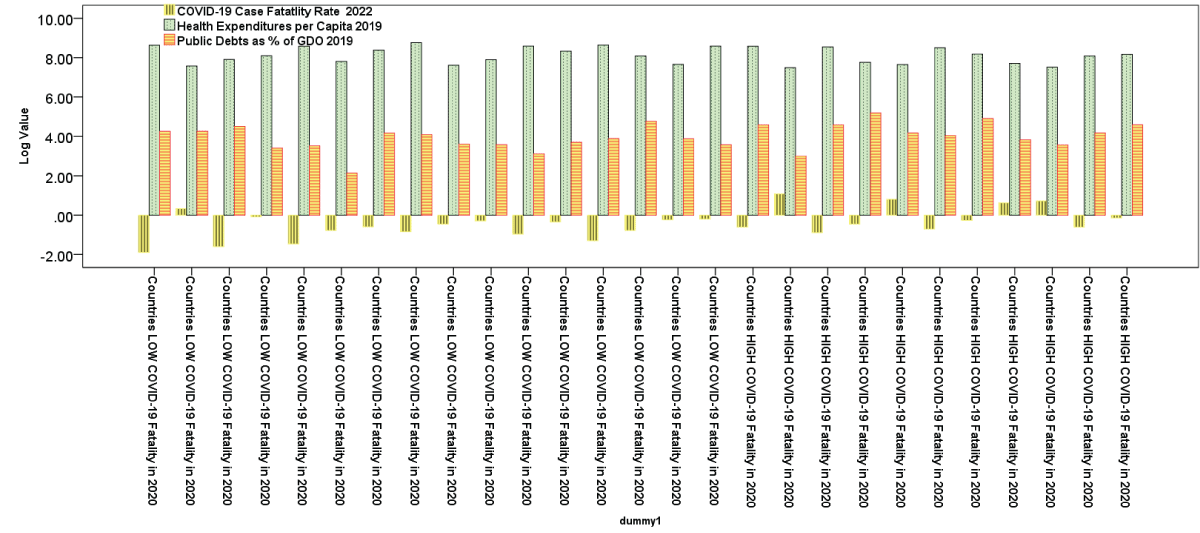

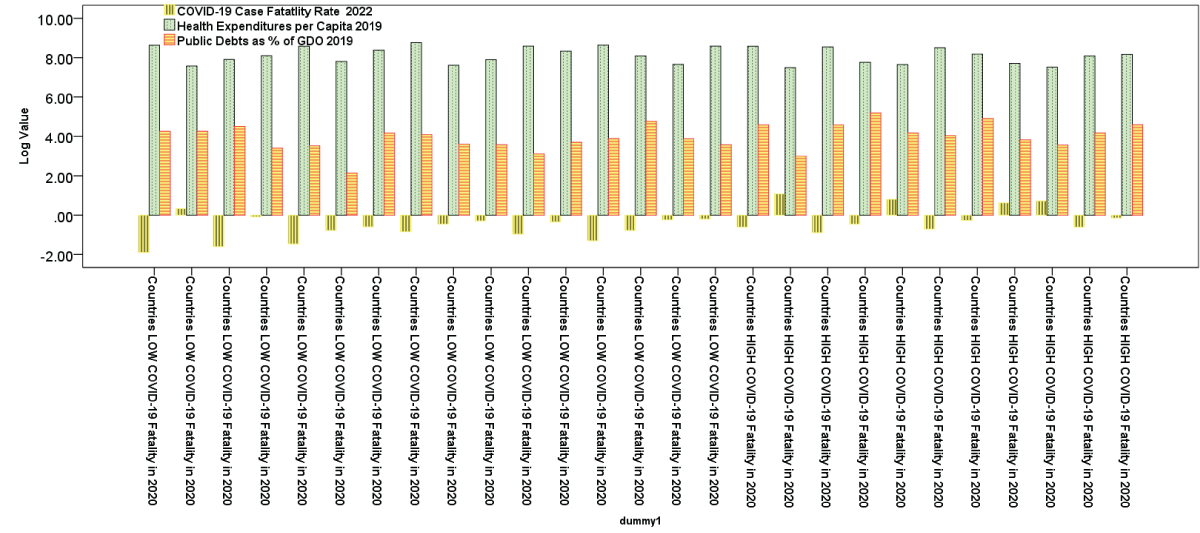

Table 4: Estimated relationship of COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022 on Healthcare Expenditure per Capita $ 2019, log-log model.Figure 1 illustrates the estimated relationship between COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022 and healthcare expenditures per capita, whereas bar graphs in Figure 2 confirm empirical analyses with a comparison of COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022, health expenditure per capita in 2019 and level of public debt in European countries of group 1 (Countries with LOWER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020) and group 2 (Countries with HIGHER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020).

Figure 1: Regression line of the COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022 on healthcare expenditures per capita in 2019.

Figure 1: Regression line of the COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022 on healthcare expenditures per capita in 2019. Figure 2: Comparison of COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022, health expenditure per capita in 2019 and level of public debt in European countries of group 1 (Countries with LOWER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020) and group 2 (Countries with HIGHER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020).

Figure 2: Comparison of COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022, health expenditure per capita in 2019 and level of public debt in European countries of group 1 (Countries with LOWER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020) and group 2 (Countries with HIGHER COVID-19 Fatality in 2020).Studies about COVID-19 discuss manifold implications about health and other socioeconomic effects [-]. What this study adds is that countries with higher fatality rates had previous high levels of public debt (0.29% of GDP), resulting in a decline in overall health expenditures over time for healthcare system. Conversely, countries with lower fatality rates, despite a lesser increase in public debt (0.12% of GDP), had a notable escalation in health expenditures per capita, totaling 0.19% of GDP. Results suggest that countries with lower levels of public debt over time are associated with greater resilience in healthcare system and consequential lower-case fatality rate of COVID-19 [,]. The susceptibility of the health system stems from the high level of public debt in certain countries, often resulting from political economy strategies based on austerity measures aimed at alleviating the burden of government debt, such as the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) in Europe, that also reduces health expenditures over time; several studies indicate that European nations striving to reduce their public debt levels adhere to the rules outlined in the SGP, also reducing the spending in health and education [,]. However, findings here show that when European countries have a 1% increase in healthcare expenditure per capita, they experienced a 1.2% reduction in the COVID-19 fatality rate. The European Central Bank [] affirms that excessive government debt leads economies to be less resilient to unforeseen shocks, crises, emergencies, etc. and the trimming of health and social expenditures is frequently a response to initiatives aimed at addressing high level of public debt. Iwata and Iiboshi [] argue that fiscal adjustments seems to be the primary factor contributing to the diminishing government spending multipliers, rather than the accumulation of debt itself. Hence, financial strategies and public finance policies that impose limitations in various European countries with significant high level of public debt tend to heighten systemic fragility and diminish the ability of health systems to effectively respond to crises and complex emergencies []. Undoubtedly, these governmental strategies fail to take into account the impact of elevated public debt on a nation’s systemic ability to withstand crises and socio-economic shock. The fundamental implications of economic policy of findings here are that countries must decrease public debt with good governance and institutions [] and steer clear of austerity measures in order to allocate more resources to the healthcare sector and enhance readiness to address unforeseen emergencies like the COVID-19 pandemic, natural calamities, conflicts, and other environmental disruptions [-].

One of the main problems for managing global crises is to clarify the drivers of systemic weakness or strength in countries to face emergencies. This study here analyzes how the level of public debt can affect healthcare expenditures and fatality rates in the presence of pandemic crises, such as COVID-19.

Main findings of the empirical evidence are that:

These conclusions are of course tentative. There is need for much more detailed research with additional data and different methods into the relations of socioeconomic factors to reduce country risk and improve the resilience of nations in the presence of emergencies and global crises.

Alesina A, Favero C, Giavazzi F. Austerity: When it works and when it doesn’t. Princeton University Press; 2019. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77f4b

Coccia M. Asymmetric paths of public debts and of general government deficits across countries within and outside the European monetary unification and economic policy of debt dissolution. J Econ Asymmetries. 2017;15:17-31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2016.10.003

Karanikolos M, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Ricciardi W, McKee M. The impact of austerity policies on health systems in Southern Europe. In: Social Welfare Issues in Southern Europe. Routledge; 2022. p. 21. Available from: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429262678-10/impact-austerity-policies-health-systems-southern-europe-marina-karanikolos-natasha-azzopardi-muscat-walter-ricciardi-martin-mckee

Levaggi R, Menoncin F. Soft budget constraints in health care: evidence from Italy. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(5):725-37. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22903300/

Crivelli E, Leive A, Stratmann MT. Subnational health spending and soft budget constraints in OECD countries. International Monetary Fund; 2010. p. 1-25. Available from: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10147.pdf

Bacchiocchi E, Borghi E, Missale A. Public investment under fiscal constraints. Fiscal Studies. 2011;32(1):11-42. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/events/2017/20170124-ecfin-workshop/documents/missale_en.pdf

Souliotis K, Papadonikolaki J, Papageorgiou M, Economou M. The impact of crisis on health and health care: Thoughts and data on the Greek case. Arch Hell Med. 2018;35(1):9-16. Available from: http://mail.mednet.gr/archives/2018-sup/9abs.html

Agoraki MK, Kardara S, Kollintzas T, Kouretas GP. Debt-to-GDP changes and the great recession: European Periphery versus European Core. Int J Finance Econ. 2023;28:3299-3331. Available from: https://www2.aueb.gr/conferences/Crete2018/Papers/Kouretas.pdf

Aizenman J, Ito H. Post COVID-19 exit strategies and emerging markets economic challenges. Rev Int Econ. 2023;31(1):1-34. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/roie.12608

Essers D, Cassimon D. Towards HIPC 2.0? Lessons from past debt relief initiatives for addressing current debt problems. JGD. 2022;13(2):187-231. Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jgd-2021-0051/html

Abel JG, Gietel-Basten S. International remittance flows and the economic and social consequences of COVID-19. Environ Plan A. 2020;52(8):1480-1482. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/a/sae/envira/v52y2020i8p1480-1482.html

Ahmed SM, Khanam M, Shuchi NS. COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A scoping review of governance issues affecting response in public sector. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2023;7:100457. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38226180/

Akan AP, Coccia M. Changes of Air Pollution between Countries Because of Lockdowns to Face COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl Sci. 2022;12(24):12806. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/24/12806

Akan AP, Coccia M. Transmission of COVID-19 in cities with weather conditions of high air humidity: Lessons learned from Turkish Black Sea region to face next pandemic crisis, COVID. 2023;3(11):1648-1662. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/3/11/113

Allen DW. Covid-19 Lockdown Cost/Benefits: A Critical Assessment of the Literature. Int J Econ Bus. 2022;29(1):1-32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2021.1976051

Amarlou A, Coccia M. Estimation of diffusion modelling of unhealthy nanoparticles by using natural and safe microparticles. Nanochemistry Research. 2023; 8(2), 117-121. doi: 10.22036/ncr.2023.02.004 Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4727728

Angelopoulos AN, Pathak R, Varma R, Jordan MI. On Identifying and Mitigating Bias in the Estimation of the COVID-19 Case Fatality Rate. Harv Data Sci Rev. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.f01ee285

Ardito L, Coccia M, Messeni Petruzzelli A. Technological exaptation and crisis management: Evidence from COVID-19 outbreaks. R&D Manage. 2021;51(4):381-392. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12455

Ball P. What the COVID-19 pandemic reveals about science, policy, and society. Interface Focus. 2021;11(6):20210022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2021.0022

Banik A, Nag T, Chowdhury SR, Chatterjee R. Why do COVID-19 fatality rates differ across countries? An explorative cross-country study based on select indicators. Glob Bus Rev. 2020;21(3):607-625. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0972150920929897

Benach J, Cash-Gibson L, Rojas-Gualdrón DF, Padilla-Pozo Á, Fernández-Gracia J, Eguíluz VM, et al.; COVID-SHINE group. Inequalities in COVID-19 inequalities research: Who had the capacity to respond? PLoS One. 2022;17(5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266132

Benati I, Coccia M. Global analysis of timely COVID-19 vaccinations: Improving governance to reinforce response policies for pandemic crises. Int J Health Govern. 2022;27(3):240-253. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHG-07-2021-0072

Coccia M, Benati I. Negative effects of high public debt on health systems facing pandemic crisis: Lessons from COVID-19 in Europe to prepare for future emergencies. AIMS Public Health. 2024;11(2):477-498. Available from: https://www.aimspress.com/article/doi/10.3934/publichealth.2024024

Coccia M, Benati I. Effective health systems facing pandemic crisis: lessons from COVID-19 in Europe for next emergencies. Int J Health Govern. 2024. Available from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJHG-02-2024-0013/full/html?skipTracking=true

Dowd JB, Andriano L, Brazel DM, Rotondi V, Block P, et al. Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(18):9696-9698. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32300018/

Elo IT, Luck A, Stokes AC, Hempstead K, Xie W, Preston SH. Evaluation of Age Patterns of COVID-19 Mortality by Race and Ethnicity from March 2020 to October 2021 in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.12686

El-Sadr WM, Vasan A, El-Mohandes A. Facing the New Covid-19 Reality. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(5):385-387. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2213920

Fisman D. Universal healthcare and the pandemic mortality gap. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(29). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2208032119

Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A, Unwin HJT, Mellan TA, Coupland H, et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020;584(7820):257-261. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32512579/

Galvani AP, Parpia AS, Pandey A, Sah P, Colón K, Friedman G, et al. Universal healthcare as pandemic preparedness: The lives and costs that could have been saved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(25). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200536119

Goolsbee A, Syverson C. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: Comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. J Public Econ. 2021;193:104311. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104311

Götz P, Auping WL, Hinrichs-Krapels S. Contributing to health system resilience during pandemics via purchasing and supply strategies: an exploratory system dynamics approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):130. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38267945/

Haghighi H, Takian A. Institutionalization for good governance to reach sustainable health development: a framework analysis. Global Health. 2024;20(1):5. Available from: https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-023-01009-5

Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung A, Tan MM, Wu S, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. 2021;27:964-980. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34002090/

Coccia M. High potential of technology to face new respiratory viruses: mechanical ventilation devices for effective healthcare to next pandemic emergencies. Technol Soc. 2023;73:102233. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102233

Coccia M. COVID-19 Vaccination is not a Sufficient Public Policy to face Crisis Management of next Pandemic Threats. Public Organiz Rev. 2023;23:1353-1367. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00661-6

Coccia M. Basic role of medical ventilators to lower COVID-19 fatality and face next pandemic crises. J Soc Adm Sci. 2024;11(1):1-26. Available from: https://journals.econsciences.com/index.php/JSAS/article/view/2469

Coccia M. General properties of the evolution of research fields: a scientometric study of human microbiome, evolutionary robotics and astrobiology. Scientometrics. 2018;117(2):1265-1283. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11192-018-2902-8

Coccia M. An introduction to the theories of institutional change. J Econ Libr. 2018;5(4):337-344. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3315603

Kluge HHP, Nitzan D, Azzopardi-Muscat N. COVID-19: reflecting on experience and anticipating the next steps. A perspective from the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Eurohealth. 2020;26(2):13-15. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/336286

Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, Leung GM, Oshitani H, Fukuda K, et al. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020 Mar 7;395(10227):848-850. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32151326/

Levin AT, Hanage WP, Owusu-Boaitey N, Cochran KB, Walsh SP, Meyerowitz-Katz G. Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020 Dec;35(12):1123-1138. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10654-020-00698-1

Magazzino C, Mele M, Coccia M. A machine learning algorithm to analyze the effects of vaccination on COVID-19 mortality. Epidemiol Infect. 2022;150. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268822001418

McKee M. European roadmap out of the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020 Apr 21;369. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/369/bmj.m1556.full.pdf

Miranda J, Barahona OM, Krüger AB, Lagos P, Moreno-Serra R. Central America and the Dominican Republic at Crossroads: The Importance of Regional Cooperation and Health Economic Research to Address Current Health Challenges. Value Health Reg Issues. 2024;39:107-114. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38086215/

Núñez-Delgado A, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Kumar M, Farkas K, Domingo JL. SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic microorganisms in the environment. Environ Res. 2021 Mar;201:111606. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111606

Núñez-Delgado A, Zhang Z, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Race M, Zhou Y. Editorial on the Topic “New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants.” Materials (Basel). 2023 Feb 27;16(2):725. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16020725

Núñez-Delgado A, Zhang Z, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Race M, Zhou Y. Topic Reprint, New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants, Volume I. MDPI. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/books/reprint/9109-new-research-on-detection-and-removal-of-emerging-pollutants

Núñez-Delgado A, Zhang Z, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Race M, Zhou Y. Topic Reprint, New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants, Volume II. MDPI. Available from: https://mdpi-res.com/bookfiles/topic/9110/New_Research_on_Detection_and_Removal_of_Emerging_Pollutants.pdf?v=1720141451

Coccia M. An introduction to the methods of inquiry in social sciences. J Soc Adm Sci. 2018;5(2):116-126. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3219016

Coccia M. An introduction to the theories of national and regional economic development. Turk Econ Rev. 2018;5(4):350-358. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3316027

Coccia M. Probability of discoveries between research fields to explain scientific and technological change. Technol Soc. 2022 Feb;68:101874. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101874

Coccia M. COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: Analysis of origins, diffusive factors and problems of lockdowns and vaccinations to design best policy responses Vol.2. KSP Books; 2023. ISBN: 978-625-7813-54-9.

Coccia M. Effects of strict containment policies on COVID-19 pandemic crisis: lessons to cope with next pandemic impacts. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Jan;30(1):2020-2028. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35925462/

Kapitsinis N. The underlying factors of the COVID-19 spatially uneven spread. Initial evidence from regions in nine EU countries. Reg Sci Policy Pract. 2020 Jun;12(6):1027-1046. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1757780223003773

Kargı B, Coccia M, Uçkaç BC. Findings from the first wave of COVID-19 on the different impacts of lockdown on public health and economic growth. Int J Econ Sci. 2023;12(2):21-39. Available from: https://eurrec.org/ijoes-article-117076

Kargı B, Coccia M, Uçkaç BC. How does the wealth level of nations affect their COVID19 vaccination plans? Econ Manage Sustain. 2023;8(2):6-19. Available from: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1213042

Kargı B, Coccia M, Uçkaç BC. The Relation Between Restriction Policies against Covid-19, Economic Growth and Mortality Rate in Society. Migration Letters. 2023;20(5):218-231. Available from: https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/view/3538

Khan JR, Awan N, Islam MM, Muurlink O. Healthcare capacity, health expenditure, and civil society as predictors of COVID-19 case fatalities: a global analysis. Front Public Health. 2020;8:347. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32719765/

Kim KM, Evans DS, Jacobson J, Jiang X, Browner W, Cummings SR. Rapid prediction of in-hospital mortality among adults with COVID-19 disease. PLoS One. 2022 Jul;17(7). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269813

Coccia M, Bontempi E. New trajectories of technologies for the removal of pollutants and emerging contaminants in the environment. Environ Res. 2023 Jul 15;229:115938. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115938. Epub 2023 Apr 20. PMID: 37086878.

Galvão MHR, Roncalli AG. Factors associated with increased risk of death from covid-19: a survival analysis based on confirmed cases. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2021 Jan 6;23:e200106. Portuguese, English. doi: 10.1590/1980-549720200106. PMID: 33439939.

Homburg S. Effectiveness of corona lockdowns: evidence for a number of countries. Economists Voice. 2020 Mar;17(1):20200010.

Jacques O, Arpin E, Ammi M, Noël A. The political and fiscal determinants of public health and curative care expenditures: evidence from the Canadian provinces, 1980-2018. Can J Public Health. 2023 Mar 23:1-9. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-023-00751-y

Penkler M, Müller R, Kenney M, Hanson M. Back to normal? Building community resilience after COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Aug;8(8):664-665. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30237-0. PMID: 32707106; PMCID: PMC7373400.

Rađenović T, Radivojević V, Krstić B, Stanišić T, Živković S. The Efficiency of Health Systems in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the EU Countries. Probl Ekorozwoju – Probl Sustain Dev. 2021;17(1):7-15.

Growing healthcare capacity to improve access to healthcare. Available from: https://www.roche.com/about/strategy/access-to-healthcare/capacity/. Accessed June 27, 2023.

Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins Center for System Science and Engineering, 2023-COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available from: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6. Accessed May 18, 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health expenditure and financing. Available from: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA. Accessed June 15, 2024.

Database. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database. Accessed July 2024.

Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Younis K, Desai P, et al. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(8):1069-1076. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00363-4. Epub 2020 Jun 25. PMID: 32838147; PMCID: PMC7314621.

Shakor JK, Isa RA, Babakir-Mina M, Ali SI, Hama-Soor TA, Abdulla JE. Health related factors contributing to COVID-19 fatality rates in various communities across the world. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021 Sep 30;15(9):1263-1272. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13876. PMID: 34669594.

Singh A. Dealing with Uncertainties During COVID-19 Pandemic: Learning from the Case Study of Bombay Mothers and Children Welfare Society (BMCWS), Mumbai, India. J Entrepreneurship Innov Emerging Econ. 2024;10(1):97-118.

Smith RW, Jarvis T, Sandhu HS, Pinto AD, O'Neill M, Di Ruggiero E, Pawa J, Rosella L, Allin S. Centralization and integration of public health systems: Perspectives of public health leaders on factors facilitating and impeding COVID-19 responses in three Canadian provinces. Health Policy. 2023;127:19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.11.011

Soltesz K, Gustafsson F, Timpka T, Jaldén J, Jidling C, et al. The effect of interventions on COVID-19. Nature. 2020 Dec;588(7839):E26-E28. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-3025-y. Epub 2020 Dec 23. PMID: 33361787.

Sorci, G., Faivre, B., & Morand, S. (2020). Explaining among-country variation in COVID-19 case fatality rate. Scientific reports, 10(1), 18909.

Tisdell CA. Economic, social and political issues raised by the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ Anal Policy. 2020 Dec;68:17-28. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2020.08.002. Epub 2020 Aug 20. PMID: 32843816; PMCID: PMC7440080.

Uçkaç BC, Coccia M, Kargi B. Diffusion COVID-19 in polluted regions: Main role of wind energy for sustainable and health. Int J Membrane Sci Technol. 2023;10(3):2755-2767. https://doi.org/10.15379/ijmst.v10i3.2286

Uçkaç BC, Coccia M, Kargı B. Simultaneous encouraging effects of new technologies for socioeconomic and environmental sustainability. Bull Soc-Econ Humanit Res. 2023;19(21):100-120. https://doi.org/10.52270/26585561_2023_19_21_100

Upadhyay AK, Shukla S. Correlation study to identify the factors affecting COVID-19 case fatality rates in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021 May-Jun;15(3):993-999. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.025. Epub 2021 May 10. PMID: 33984819; PMCID: PMC8110283.

Verma AK, Prakash S. Impact of covid-19 on environment and society. J Global Biosci. 2020;9(5):7352-7363.

Wieland T. A phenomenological approach to assessing the effectiveness of COVID-19 related nonpharmaceutical interventions in Germany. Saf Sci. 2020 Nov;131:104924. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104924. Epub 2020 Jul 21. PMID: 32834516; PMCID: PMC7373035.

Wolff D, Nee S, Hickey NS, Marschollek M. Risk factors for Covid-19 severity and fatality: a structured literature review. Infection. 2021 Feb;49(1):15-28. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01509-1. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32860214; PMCID: PMC7453858.

Zhang N, Jack Chan PT, Jia W, Dung CH, Zhao P, et al. Analysis of efficacy of intervention strategies for COVID-19 transmission: A case study of Hong Kong. Environ Int. 2021 Nov;156:106723. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106723. Epub 2021 Jun 18. PMID: 34161908; PMCID: PMC8214805.

Aboelnaga S, Czech K, Wielechowski M, Kotyza P, Smutka L, Ndue K. COVID-19 resilience index in European Union countries based on their risk and readiness scale. PLoS One. 2023 Aug 18;18(8). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289615. PMID: 37540717; PMCID: PMC10403121.

Almeida A. The trade-off between health system resiliency and efficiency: evidence from COVID-19 in European regions. Eur J Health Econ. 2024 Feb;25(1):31-47. doi: 10.1007/s10198-023-01567-w. Epub 2023 Feb 2. PMID: 36729309; PMCID: PMC9893956.

Sagan A, Erin W, Dheepa R, Marina K, Scott LG. Health system resilience during the pandemic: It’s mostly about governance. Eurohealth. 2021;27(1):10-15.

Sagan A, Thomas S, McKee M, Karanikolos M, Azzopardi-Muscat N, de la Mata I, et al. COVID-19 and health systems resilience: lessons going forwards. Eurohealth. 2020;26(2):20-24.

Theodoropoulou S. Recovery, resilience and growth regimes under overlapping EU conditionalities: the case of Greece. CEP. 2022;20:201-219.

European Central Bank (ECB). Government debt reduction strategies in the Euro area. Econ Bull. 2016;4:1-20.

Iwata Y, IIboshi H. The nexus between public debt and the government spending multiplier: fiscal adjustments matter. Oxf Bull Econ Stat. 2023;85:830-858. https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12547

Benati I, Coccia M. Effective Contact Tracing System Minimizes COVID-19 Related Infections and Deaths: Policy Lessons to Reduce the Impact of Future Pandemic Diseases. J Public Adm Governance. 2022;12(3):19-33. https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v12i3.19834

Coccia M. Comparative Institutional Changes. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1277-1

Barro RJ. Non-pharmaceutical interventions and mortality in U.S. cities during the great influenza pandemic, 1918-1919. Res Econ. 2022 Jun;76(2):93-106. doi: 10.1016/j.rie.2022.06.001. Epub 2022 Jun 25. PMID: 35784011; PMCID: PMC9232401.

Bo Y, Guo C, Lin C, Zeng Y, Li HB, Zhang Y, et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 transmission in 190 countries from 23 January to 13 April 2020. Int J Infect Dis. 2021 Jan;102:247-253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.066. Epub 2020 Oct 29. PMID: 33129965; PMCID: PMC7598763.

Bontempi E, Coccia M. International trade as critical parameter of COVID-19 spread that outclasses demographic, economic, environmental, and pollution factors. Environ Res. 2021 Oct;201:111514. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111514. Epub 2021 Jun 15. PMID: 34139222; PMCID: PMC8204848.

Bontempi E, Coccia M, Vergalli S, Zanoletti A. Can commercial trade represent the main indicator of the COVID-19 diffusion due to human-to-human interactions? A comparative analysis between Italy, France, and Spain. Environ Res. 2021;201:111529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111529

Brauner JM, Mindermann S, Sharma M, Johnston D, Salvatier J, Gavenčiak T, et al. The effectiveness of eight nonpharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19 in 41 countries. MedRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.28.20116129

Cao Y, Hiyoshi A, Montgomery S. COVID-19 case-fatality rate and demographic and socioeconomic influencers: worldwide spatial regression analysis based on country-level data. BMJ Open. 2020 Nov 3;10(11):e043560. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043560. PMID: 33148769; PMCID: PMC7640588.

Chowdhury T, Chowdhury H, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Masrur H, Sait SM, et al. Are mega-events super spreaders of infectious diseases similar to COVID-19? A look into Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics to improve preparedness of next international events. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Jan;30(4):10099-10109. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22660-2. Epub 2022 Sep 6. PMID: 36066799; PMCID: PMC9446650.

Coccia M. Socio-cultural origins of the patterns of technological innovation: What is the likely interaction among religious culture, religious plurality and innovation? Towards a theory of socio-cultural drivers of the patterns of technological innovation. Technol Soc. 2014;36(1):13-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2013.11.002

Coccia M. Radical innovations as drivers of breakthroughs: characteristics and properties of the management of technology leading to superior organizational performance in the discovery process of R&D labs. Technol Anal Strategic Manage. 2016;28(4):381-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2015.1095287

Coccia M. Intrinsic and extrinsic incentives to support motivation and performance of public organizations. J Econ Bibliogr. 2019;6(1):20-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jeb.v6i1.1795

Coccia M. Comparative Incentive Systems. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3706-1

Coccia M. Theories of Development. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_939-1

Coccia M. An index to quantify environmental risk of exposure to future epidemics of the COVID-19 and similar viral agents: Theory and practice. Environ Res. 2020 Dec;191:110155. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110155. Epub 2020 Aug 29. PMID: 32871151; PMCID: PMC7834384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110155

Coccia M. Effects of Air Pollution on COVID-19 and Public Health. ResearchSquare. 2020. DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-41354/v1

Coccia M. Asymmetry of the technological cycle of disruptive innovations. Technol Anal Strategic Manage. 2020;32(12):1462-1477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2020.1785415

Coccia M. Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Sci Total Environ. 2020 Aug 10;729:138474. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474. Epub 2020 Apr 20. PMID: 32498152; PMCID: PMC7169901.

Coccia M. How (Un)sustainable Environments are Related to the Diffusion of COVID-19: The Relation between Coronavirus Disease 2019, Air Pollution, Wind Resource and Energy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229709

Coccia M. Comparative Critical Decisions in Management. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer Nature; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3969-1

Coccia M. The relation between length of lockdown, numbers of infected people and deaths of COVID-19, and economic growth of countries: Lessons learned to cope with future pandemics similar to COVID-19. Science of The Total Environment, 2021a; 775:145801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145801

Coccia M. Pandemic Prevention: Lessons from COVID-19. Encyclopedia. 2021b; 1:2; 433-444. doi: 10.3390/encyclopedia1020036

Coccia M. Different effects of lockdown on public health and economy of countries: Results from first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Economics Library. 2021c; 8(1):45-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jel.v8i1.2183

Coccia M. Recurring waves of Covid-19 pandemic with different effects in public health, Journal of Economics Bibliography. 2021d; 8:1; 28-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jeb.v8i1.2184

Coccia M. High health expenditures and low exposure of population to air pollution as critical factors that can reduce fatality rate in COVID-19 pandemic crisis: a global analysis. Environ Res. 2021 Aug;199:111339. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111339. Epub 2021 May 21. PMID: 34029545; PMCID: PMC8139437.

Coccia M. How do low wind speeds and high levels of air pollution support the spread of COVID-19? Atmos Pollut Res. 2021 Jan;12(1):437-445. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2020.10.002. Epub 2020 Oct 7. PMID: 33046960; PMCID: PMC7541047.

Coccia M. Evolution and structure of research fields driven by crises and environmental threats: the COVID-19 research. Scientometrics. 2021;126(12):9405-9429. doi: 10.1007/s11192-021-04172-x. Epub 2021 Oct 24. PMID: 34720251; PMCID: PMC8541882.

Coccia M. The impact of first and second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in society: comparative analysis to support control measures to cope with negative effects of future infectious diseases. Environ Res. 2021 Jun;197:111099. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111099. Epub 2021 Apr 2. PMID: 33819476; PMCID: PMC8017951.

Coccia M. Effects of human progress driven by technological change on physical and mental health, STUDI DI SOCIOLOGIA. 2021i; 2:113-132. https://doi.org/10.26350/000309_000116

Coccia M. Effects of the spread of COVID-19 on public health of polluted cities: results of the first wave for explaining the dejà vu in the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic and epidemics of future vital agents. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 Apr;28(15):19147-19154. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11662-7. Epub 2021 Jan 4. PMID: 33398753; PMCID: PMC7781409.

Coccia M. Critical decisions for crisis management: An introduction. J. Adm. Soc. Sci. 2021m; 8:1; 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jsas.v8i1.2181

Coccia M. Meta-analysis to explain unknown causes of the origins of SARS-COV-2. Environ Res. 2022 Aug;211:113062. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113062. Epub 2022 Mar 5. PMID: 35259407; PMCID: PMC8897286.

Coccia M. COVID-19 Vaccination is not a Sufficient Public Policy to face Crisis Management of next Pandemic Threats. Public Organization Review. 2022a; 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00661-6

Coccia M. Effects of strict containment policies on COVID-19 pandemic crisis: lessons to cope with next pandemic impacts. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Jan;30(1):2020-2028. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22024-w. Epub 2022 Aug 4. PMID: 35925462; PMCID: PMC9362501.

Coccia M. Improving preparedness for next pandemics: Max level of COVID-19 vaccinations without social impositions to design effective health policy and avoid flawed democracies. Environ Res. 2022 Oct;213:113566. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113566. Epub 2022 May 31. PMID: 35660409; PMCID: PMC9155186.

Coccia M. Optimal levels of vaccination to reduce COVID-19 infected individuals and deaths: A global analysis. Environ Res. 2022 Mar;204(Pt C):112314. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112314. Epub 2021 Nov 2. PMID: 34736923; PMCID: PMC8560189.

Coccia M. Preparedness of countries to face COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Strategic positioning and factors supporting effective strategies of prevention of pandemic threats. Environ Res. 2022 Jan;203:111678. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111678. Epub 2021 Jul 16. PMID: 34280421; PMCID: PMC8284056.

Coccia M. COVID-19 pandemic over 2020 (withlockdowns) and 2021 (with vaccinations): similar effects for seasonality and environmental factors. Environ Res. 2022 May 15;208:112711. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112711. Epub 2022 Jan 13. PMID: 35033552; PMCID: PMC8757643.

Coccia M. The Spread of the Novel Coronavirus Disease-2019 in Polluted Cities: Environmental and Demographic Factors to Control for the Prevention of Future Pandemic Diseases. In: Faghih N, Forouharfar A. (eds) Socioeconomic Dynamics of the COVID-19 Crisis. Contributions to Economics: Springer, Cham. 2022g; 351-369. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89996-7_16

Coccia M. Sources, diffusion and prediction in COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned to face next health emergency. AIMS Public Health. 2023 Mar 2;10(1):145-168. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2023012. PMID: 37063362; PMCID: PMC10091135.

Coccia M, Benati I. Comparative Evaluation Systems, A. Farazmand (ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1210-1

Coccia M, Benati I. Comparative Studies. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance –section Bureaucracy (edited by Ali Farazmand). Springer, Cham. 2018a; Chapter No. 1197-1:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1197-1

Coccia M, Benati I. Effective health systems facing pandemic crisis: lessons from COVID-19 in Europe for next emergencies, International Journal of Health Governance. 2024a. DOI 10.1108/IJHG-02-2024-0013

Núñez-Delgado A, Bontempi E, Zhou Y, Álvarez-Rodríguez E, López-Ramón MV, Coccia M, Zhang Z, Santás-Miguel V, Race M. Editorial of the Topic “Environmental and Health Issues and Solutions for Anticoccidials and other Emerging Pollutants of Special Concern”. Processes. 2024; 12(7):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12071379

Coccia M. Country Risk to Face Global Emergencies: Negative Effects of High Public Debt on Health Expenditures and Fatality Rate in COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. IgMin Res. Jul 06, 2024; 2(7): 537-545. IgMin ID: igmin214; DOI:10.61927/igmin214; Available at: igmin.link/p214

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

Address Correspondence:

Mario Coccia, CNR-National Research Council of Italy, Italy, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Coccia M. Country Risk to Face Global Emergencies: Negative Effects of High Public Debt on Health Expenditures and Fatality Rate in COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis. IgMin Res. Jul 06, 2024; 2(7): 537-545. IgMin ID: igmin214; DOI:10.61927/igmin214; Available at: igmin.link/p214

Copyright: © 2024 Coccia M. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Figure 1: Regression line of the COVID-19 fatality rate in 2...

Figure 1: Regression line of the COVID-19 fatality rate in 2...

Figure 2: Comparison of COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022, heal...

Figure 2: Comparison of COVID-19 fatality rate in 2022, heal...

Table 1: Descriptive statistics categorized per groups....

Table 1: Descriptive statistics categorized per groups....

Table 2: Independent Samples T-Test based on average mean a...

Table 2: Independent Samples T-Test based on average mean a...

Table 3: Bivariate correlation between health expenditure a...

Table 3: Bivariate correlation between health expenditure a...

Table 4: Estimated relationship of COVID-19 fatality rate i...

Table 4: Estimated relationship of COVID-19 fatality rate i...

Alesina A, Favero C, Giavazzi F. Austerity: When it works and when it doesn’t. Princeton University Press; 2019. Available from: https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvc77f4b

Coccia M. Asymmetric paths of public debts and of general government deficits across countries within and outside the European monetary unification and economic policy of debt dissolution. J Econ Asymmetries. 2017;15:17-31. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeca.2016.10.003

Karanikolos M, Azzopardi-Muscat N, Ricciardi W, McKee M. The impact of austerity policies on health systems in Southern Europe. In: Social Welfare Issues in Southern Europe. Routledge; 2022. p. 21. Available from: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429262678-10/impact-austerity-policies-health-systems-southern-europe-marina-karanikolos-natasha-azzopardi-muscat-walter-ricciardi-martin-mckee

Levaggi R, Menoncin F. Soft budget constraints in health care: evidence from Italy. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(5):725-37. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22903300/

Crivelli E, Leive A, Stratmann MT. Subnational health spending and soft budget constraints in OECD countries. International Monetary Fund; 2010. p. 1-25. Available from: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10147.pdf

Bacchiocchi E, Borghi E, Missale A. Public investment under fiscal constraints. Fiscal Studies. 2011;32(1):11-42. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/events/2017/20170124-ecfin-workshop/documents/missale_en.pdf

Souliotis K, Papadonikolaki J, Papageorgiou M, Economou M. The impact of crisis on health and health care: Thoughts and data on the Greek case. Arch Hell Med. 2018;35(1):9-16. Available from: http://mail.mednet.gr/archives/2018-sup/9abs.html

Agoraki MK, Kardara S, Kollintzas T, Kouretas GP. Debt-to-GDP changes and the great recession: European Periphery versus European Core. Int J Finance Econ. 2023;28:3299-3331. Available from: https://www2.aueb.gr/conferences/Crete2018/Papers/Kouretas.pdf

Aizenman J, Ito H. Post COVID-19 exit strategies and emerging markets economic challenges. Rev Int Econ. 2023;31(1):1-34. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/roie.12608

Essers D, Cassimon D. Towards HIPC 2.0? Lessons from past debt relief initiatives for addressing current debt problems. JGD. 2022;13(2):187-231. Available from: https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/jgd-2021-0051/html

Abel JG, Gietel-Basten S. International remittance flows and the economic and social consequences of COVID-19. Environ Plan A. 2020;52(8):1480-1482. Available from: https://ideas.repec.org/a/sae/envira/v52y2020i8p1480-1482.html

Ahmed SM, Khanam M, Shuchi NS. COVID-19 pandemic in Bangladesh: A scoping review of governance issues affecting response in public sector. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2023;7:100457. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38226180/

Akan AP, Coccia M. Changes of Air Pollution between Countries Because of Lockdowns to Face COVID-19 Pandemic. Appl Sci. 2022;12(24):12806. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/24/12806

Akan AP, Coccia M. Transmission of COVID-19 in cities with weather conditions of high air humidity: Lessons learned from Turkish Black Sea region to face next pandemic crisis, COVID. 2023;3(11):1648-1662. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2673-8112/3/11/113

Allen DW. Covid-19 Lockdown Cost/Benefits: A Critical Assessment of the Literature. Int J Econ Bus. 2022;29(1):1-32. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/13571516.2021.1976051

Amarlou A, Coccia M. Estimation of diffusion modelling of unhealthy nanoparticles by using natural and safe microparticles. Nanochemistry Research. 2023; 8(2), 117-121. doi: 10.22036/ncr.2023.02.004 Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4727728

Angelopoulos AN, Pathak R, Varma R, Jordan MI. On Identifying and Mitigating Bias in the Estimation of the COVID-19 Case Fatality Rate. Harv Data Sci Rev. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.f01ee285

Ardito L, Coccia M, Messeni Petruzzelli A. Technological exaptation and crisis management: Evidence from COVID-19 outbreaks. R&D Manage. 2021;51(4):381-392. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12455

Ball P. What the COVID-19 pandemic reveals about science, policy, and society. Interface Focus. 2021;11(6):20210022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsfs.2021.0022

Banik A, Nag T, Chowdhury SR, Chatterjee R. Why do COVID-19 fatality rates differ across countries? An explorative cross-country study based on select indicators. Glob Bus Rev. 2020;21(3):607-625. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0972150920929897

Benach J, Cash-Gibson L, Rojas-Gualdrón DF, Padilla-Pozo Á, Fernández-Gracia J, Eguíluz VM, et al.; COVID-SHINE group. Inequalities in COVID-19 inequalities research: Who had the capacity to respond? PLoS One. 2022;17(5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0266132

Benati I, Coccia M. Global analysis of timely COVID-19 vaccinations: Improving governance to reinforce response policies for pandemic crises. Int J Health Govern. 2022;27(3):240-253. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHG-07-2021-0072

Coccia M, Benati I. Negative effects of high public debt on health systems facing pandemic crisis: Lessons from COVID-19 in Europe to prepare for future emergencies. AIMS Public Health. 2024;11(2):477-498. Available from: https://www.aimspress.com/article/doi/10.3934/publichealth.2024024

Coccia M, Benati I. Effective health systems facing pandemic crisis: lessons from COVID-19 in Europe for next emergencies. Int J Health Govern. 2024. Available from: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/IJHG-02-2024-0013/full/html?skipTracking=true

Dowd JB, Andriano L, Brazel DM, Rotondi V, Block P, et al. Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(18):9696-9698. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32300018/

Elo IT, Luck A, Stokes AC, Hempstead K, Xie W, Preston SH. Evaluation of Age Patterns of COVID-19 Mortality by Race and Ethnicity from March 2020 to October 2021 in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.12686

El-Sadr WM, Vasan A, El-Mohandes A. Facing the New Covid-19 Reality. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(5):385-387. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2213920

Fisman D. Universal healthcare and the pandemic mortality gap. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(29). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2208032119

Flaxman S, Mishra S, Gandy A, Unwin HJT, Mellan TA, Coupland H, et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020;584(7820):257-261. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32512579/

Galvani AP, Parpia AS, Pandey A, Sah P, Colón K, Friedman G, et al. Universal healthcare as pandemic preparedness: The lives and costs that could have been saved during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022;119(25). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2200536119

Goolsbee A, Syverson C. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: Comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. J Public Econ. 2021;193:104311. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104311

Götz P, Auping WL, Hinrichs-Krapels S. Contributing to health system resilience during pandemics via purchasing and supply strategies: an exploratory system dynamics approach. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24(1):130. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38267945/

Haghighi H, Takian A. Institutionalization for good governance to reach sustainable health development: a framework analysis. Global Health. 2024;20(1):5. Available from: https://globalizationandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12992-023-01009-5

Haldane V, De Foo C, Abdalla SM, Jung A, Tan MM, Wu S, et al. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat Med. 2021;27:964-980. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34002090/

Coccia M. High potential of technology to face new respiratory viruses: mechanical ventilation devices for effective healthcare to next pandemic emergencies. Technol Soc. 2023;73:102233. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102233

Coccia M. COVID-19 Vaccination is not a Sufficient Public Policy to face Crisis Management of next Pandemic Threats. Public Organiz Rev. 2023;23:1353-1367. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00661-6

Coccia M. Basic role of medical ventilators to lower COVID-19 fatality and face next pandemic crises. J Soc Adm Sci. 2024;11(1):1-26. Available from: https://journals.econsciences.com/index.php/JSAS/article/view/2469

Coccia M. General properties of the evolution of research fields: a scientometric study of human microbiome, evolutionary robotics and astrobiology. Scientometrics. 2018;117(2):1265-1283. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11192-018-2902-8

Coccia M. An introduction to the theories of institutional change. J Econ Libr. 2018;5(4):337-344. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3315603

Kluge HHP, Nitzan D, Azzopardi-Muscat N. COVID-19: reflecting on experience and anticipating the next steps. A perspective from the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Eurohealth. 2020;26(2):13-15. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/336286

Legido-Quigley H, Asgari N, Teo YY, Leung GM, Oshitani H, Fukuda K, et al. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet. 2020 Mar 7;395(10227):848-850. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32151326/

Levin AT, Hanage WP, Owusu-Boaitey N, Cochran KB, Walsh SP, Meyerowitz-Katz G. Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020 Dec;35(12):1123-1138. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10654-020-00698-1

Magazzino C, Mele M, Coccia M. A machine learning algorithm to analyze the effects of vaccination on COVID-19 mortality. Epidemiol Infect. 2022;150. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268822001418

McKee M. European roadmap out of the covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020 Apr 21;369. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/369/bmj.m1556.full.pdf

Miranda J, Barahona OM, Krüger AB, Lagos P, Moreno-Serra R. Central America and the Dominican Republic at Crossroads: The Importance of Regional Cooperation and Health Economic Research to Address Current Health Challenges. Value Health Reg Issues. 2024;39:107-114. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38086215/

Núñez-Delgado A, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Kumar M, Farkas K, Domingo JL. SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogenic microorganisms in the environment. Environ Res. 2021 Mar;201:111606. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111606

Núñez-Delgado A, Zhang Z, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Race M, Zhou Y. Editorial on the Topic “New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants.” Materials (Basel). 2023 Feb 27;16(2):725. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16020725

Núñez-Delgado A, Zhang Z, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Race M, Zhou Y. Topic Reprint, New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants, Volume I. MDPI. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/books/reprint/9109-new-research-on-detection-and-removal-of-emerging-pollutants

Núñez-Delgado A, Zhang Z, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Race M, Zhou Y. Topic Reprint, New Research on Detection and Removal of Emerging Pollutants, Volume II. MDPI. Available from: https://mdpi-res.com/bookfiles/topic/9110/New_Research_on_Detection_and_Removal_of_Emerging_Pollutants.pdf?v=1720141451

Coccia M. An introduction to the methods of inquiry in social sciences. J Soc Adm Sci. 2018;5(2):116-126. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3219016

Coccia M. An introduction to the theories of national and regional economic development. Turk Econ Rev. 2018;5(4):350-358. Available from: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3316027

Coccia M. Probability of discoveries between research fields to explain scientific and technological change. Technol Soc. 2022 Feb;68:101874. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101874

Coccia M. COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis: Analysis of origins, diffusive factors and problems of lockdowns and vaccinations to design best policy responses Vol.2. KSP Books; 2023. ISBN: 978-625-7813-54-9.

Coccia M. Effects of strict containment policies on COVID-19 pandemic crisis: lessons to cope with next pandemic impacts. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Jan;30(1):2020-2028. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35925462/

Kapitsinis N. The underlying factors of the COVID-19 spatially uneven spread. Initial evidence from regions in nine EU countries. Reg Sci Policy Pract. 2020 Jun;12(6):1027-1046. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1757780223003773

Kargı B, Coccia M, Uçkaç BC. Findings from the first wave of COVID-19 on the different impacts of lockdown on public health and economic growth. Int J Econ Sci. 2023;12(2):21-39. Available from: https://eurrec.org/ijoes-article-117076

Kargı B, Coccia M, Uçkaç BC. How does the wealth level of nations affect their COVID19 vaccination plans? Econ Manage Sustain. 2023;8(2):6-19. Available from: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1213042

Kargı B, Coccia M, Uçkaç BC. The Relation Between Restriction Policies against Covid-19, Economic Growth and Mortality Rate in Society. Migration Letters. 2023;20(5):218-231. Available from: https://migrationletters.com/index.php/ml/article/view/3538

Khan JR, Awan N, Islam MM, Muurlink O. Healthcare capacity, health expenditure, and civil society as predictors of COVID-19 case fatalities: a global analysis. Front Public Health. 2020;8:347. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32719765/

Kim KM, Evans DS, Jacobson J, Jiang X, Browner W, Cummings SR. Rapid prediction of in-hospital mortality among adults with COVID-19 disease. PLoS One. 2022 Jul;17(7). Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0269813

Coccia M, Bontempi E. New trajectories of technologies for the removal of pollutants and emerging contaminants in the environment. Environ Res. 2023 Jul 15;229:115938. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115938. Epub 2023 Apr 20. PMID: 37086878.

Galvão MHR, Roncalli AG. Factors associated with increased risk of death from covid-19: a survival analysis based on confirmed cases. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2021 Jan 6;23:e200106. Portuguese, English. doi: 10.1590/1980-549720200106. PMID: 33439939.

Homburg S. Effectiveness of corona lockdowns: evidence for a number of countries. Economists Voice. 2020 Mar;17(1):20200010.

Jacques O, Arpin E, Ammi M, Noël A. The political and fiscal determinants of public health and curative care expenditures: evidence from the Canadian provinces, 1980-2018. Can J Public Health. 2023 Mar 23:1-9. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-023-00751-y

Penkler M, Müller R, Kenney M, Hanson M. Back to normal? Building community resilience after COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020 Aug;8(8):664-665. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30237-0. PMID: 32707106; PMCID: PMC7373400.

Rađenović T, Radivojević V, Krstić B, Stanišić T, Živković S. The Efficiency of Health Systems in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the EU Countries. Probl Ekorozwoju – Probl Sustain Dev. 2021;17(1):7-15.

Growing healthcare capacity to improve access to healthcare. Available from: https://www.roche.com/about/strategy/access-to-healthcare/capacity/. Accessed June 27, 2023.

Johns Hopkins University. Johns Hopkins Center for System Science and Engineering, 2023-COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available from: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6. Accessed May 18, 2023.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health expenditure and financing. Available from: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA. Accessed June 15, 2024.

Database. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database. Accessed July 2024.

Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Marinkovic A, Patidar R, Younis K, Desai P, et al. Comorbidity and its Impact on Patients with COVID-19. SN Compr Clin Med. 2020;2(8):1069-1076. doi: 10.1007/s42399-020-00363-4. Epub 2020 Jun 25. PMID: 32838147; PMCID: PMC7314621.

Shakor JK, Isa RA, Babakir-Mina M, Ali SI, Hama-Soor TA, Abdulla JE. Health related factors contributing to COVID-19 fatality rates in various communities across the world. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021 Sep 30;15(9):1263-1272. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13876. PMID: 34669594.

Singh A. Dealing with Uncertainties During COVID-19 Pandemic: Learning from the Case Study of Bombay Mothers and Children Welfare Society (BMCWS), Mumbai, India. J Entrepreneurship Innov Emerging Econ. 2024;10(1):97-118.

Smith RW, Jarvis T, Sandhu HS, Pinto AD, O'Neill M, Di Ruggiero E, Pawa J, Rosella L, Allin S. Centralization and integration of public health systems: Perspectives of public health leaders on factors facilitating and impeding COVID-19 responses in three Canadian provinces. Health Policy. 2023;127:19-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.11.011

Soltesz K, Gustafsson F, Timpka T, Jaldén J, Jidling C, et al. The effect of interventions on COVID-19. Nature. 2020 Dec;588(7839):E26-E28. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-3025-y. Epub 2020 Dec 23. PMID: 33361787.

Sorci, G., Faivre, B., & Morand, S. (2020). Explaining among-country variation in COVID-19 case fatality rate. Scientific reports, 10(1), 18909.

Tisdell CA. Economic, social and political issues raised by the COVID-19 pandemic. Econ Anal Policy. 2020 Dec;68:17-28. doi: 10.1016/j.eap.2020.08.002. Epub 2020 Aug 20. PMID: 32843816; PMCID: PMC7440080.

Uçkaç BC, Coccia M, Kargi B. Diffusion COVID-19 in polluted regions: Main role of wind energy for sustainable and health. Int J Membrane Sci Technol. 2023;10(3):2755-2767. https://doi.org/10.15379/ijmst.v10i3.2286

Uçkaç BC, Coccia M, Kargı B. Simultaneous encouraging effects of new technologies for socioeconomic and environmental sustainability. Bull Soc-Econ Humanit Res. 2023;19(21):100-120. https://doi.org/10.52270/26585561_2023_19_21_100

Upadhyay AK, Shukla S. Correlation study to identify the factors affecting COVID-19 case fatality rates in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021 May-Jun;15(3):993-999. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.04.025. Epub 2021 May 10. PMID: 33984819; PMCID: PMC8110283.

Verma AK, Prakash S. Impact of covid-19 on environment and society. J Global Biosci. 2020;9(5):7352-7363.

Wieland T. A phenomenological approach to assessing the effectiveness of COVID-19 related nonpharmaceutical interventions in Germany. Saf Sci. 2020 Nov;131:104924. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104924. Epub 2020 Jul 21. PMID: 32834516; PMCID: PMC7373035.

Wolff D, Nee S, Hickey NS, Marschollek M. Risk factors for Covid-19 severity and fatality: a structured literature review. Infection. 2021 Feb;49(1):15-28. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01509-1. Epub 2020 Aug 28. PMID: 32860214; PMCID: PMC7453858.

Zhang N, Jack Chan PT, Jia W, Dung CH, Zhao P, et al. Analysis of efficacy of intervention strategies for COVID-19 transmission: A case study of Hong Kong. Environ Int. 2021 Nov;156:106723. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.106723. Epub 2021 Jun 18. PMID: 34161908; PMCID: PMC8214805.

Aboelnaga S, Czech K, Wielechowski M, Kotyza P, Smutka L, Ndue K. COVID-19 resilience index in European Union countries based on their risk and readiness scale. PLoS One. 2023 Aug 18;18(8). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0289615. PMID: 37540717; PMCID: PMC10403121.

Almeida A. The trade-off between health system resiliency and efficiency: evidence from COVID-19 in European regions. Eur J Health Econ. 2024 Feb;25(1):31-47. doi: 10.1007/s10198-023-01567-w. Epub 2023 Feb 2. PMID: 36729309; PMCID: PMC9893956.

Sagan A, Erin W, Dheepa R, Marina K, Scott LG. Health system resilience during the pandemic: It’s mostly about governance. Eurohealth. 2021;27(1):10-15.

Sagan A, Thomas S, McKee M, Karanikolos M, Azzopardi-Muscat N, de la Mata I, et al. COVID-19 and health systems resilience: lessons going forwards. Eurohealth. 2020;26(2):20-24.

Theodoropoulou S. Recovery, resilience and growth regimes under overlapping EU conditionalities: the case of Greece. CEP. 2022;20:201-219.

European Central Bank (ECB). Government debt reduction strategies in the Euro area. Econ Bull. 2016;4:1-20.

Iwata Y, IIboshi H. The nexus between public debt and the government spending multiplier: fiscal adjustments matter. Oxf Bull Econ Stat. 2023;85:830-858. https://doi.org/10.1111/obes.12547

Benati I, Coccia M. Effective Contact Tracing System Minimizes COVID-19 Related Infections and Deaths: Policy Lessons to Reduce the Impact of Future Pandemic Diseases. J Public Adm Governance. 2022;12(3):19-33. https://doi.org/10.5296/jpag.v12i3.19834

Coccia M. Comparative Institutional Changes. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1277-1

Barro RJ. Non-pharmaceutical interventions and mortality in U.S. cities during the great influenza pandemic, 1918-1919. Res Econ. 2022 Jun;76(2):93-106. doi: 10.1016/j.rie.2022.06.001. Epub 2022 Jun 25. PMID: 35784011; PMCID: PMC9232401.

Bo Y, Guo C, Lin C, Zeng Y, Li HB, Zhang Y, et al. Effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 transmission in 190 countries from 23 January to 13 April 2020. Int J Infect Dis. 2021 Jan;102:247-253. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.10.066. Epub 2020 Oct 29. PMID: 33129965; PMCID: PMC7598763.

Bontempi E, Coccia M. International trade as critical parameter of COVID-19 spread that outclasses demographic, economic, environmental, and pollution factors. Environ Res. 2021 Oct;201:111514. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111514. Epub 2021 Jun 15. PMID: 34139222; PMCID: PMC8204848.

Bontempi E, Coccia M, Vergalli S, Zanoletti A. Can commercial trade represent the main indicator of the COVID-19 diffusion due to human-to-human interactions? A comparative analysis between Italy, France, and Spain. Environ Res. 2021;201:111529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111529

Brauner JM, Mindermann S, Sharma M, Johnston D, Salvatier J, Gavenčiak T, et al. The effectiveness of eight nonpharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19 in 41 countries. MedRxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.28.20116129

Cao Y, Hiyoshi A, Montgomery S. COVID-19 case-fatality rate and demographic and socioeconomic influencers: worldwide spatial regression analysis based on country-level data. BMJ Open. 2020 Nov 3;10(11):e043560. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043560. PMID: 33148769; PMCID: PMC7640588.

Chowdhury T, Chowdhury H, Bontempi E, Coccia M, Masrur H, Sait SM, et al. Are mega-events super spreaders of infectious diseases similar to COVID-19? A look into Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics to improve preparedness of next international events. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Jan;30(4):10099-10109. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22660-2. Epub 2022 Sep 6. PMID: 36066799; PMCID: PMC9446650.

Coccia M. Socio-cultural origins of the patterns of technological innovation: What is the likely interaction among religious culture, religious plurality and innovation? Towards a theory of socio-cultural drivers of the patterns of technological innovation. Technol Soc. 2014;36(1):13-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2013.11.002

Coccia M. Radical innovations as drivers of breakthroughs: characteristics and properties of the management of technology leading to superior organizational performance in the discovery process of R&D labs. Technol Anal Strategic Manage. 2016;28(4):381-395. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2015.1095287

Coccia M. Intrinsic and extrinsic incentives to support motivation and performance of public organizations. J Econ Bibliogr. 2019;6(1):20-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jeb.v6i1.1795

Coccia M. Comparative Incentive Systems. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3706-1

Coccia M. Theories of Development. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_939-1

Coccia M. An index to quantify environmental risk of exposure to future epidemics of the COVID-19 and similar viral agents: Theory and practice. Environ Res. 2020 Dec;191:110155. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110155. Epub 2020 Aug 29. PMID: 32871151; PMCID: PMC7834384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.110155

Coccia M. Effects of Air Pollution on COVID-19 and Public Health. ResearchSquare. 2020. DOI:10.21203/rs.3.rs-41354/v1

Coccia M. Asymmetry of the technological cycle of disruptive innovations. Technol Anal Strategic Manage. 2020;32(12):1462-1477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2020.1785415

Coccia M. Factors determining the diffusion of COVID-19 and suggested strategy to prevent future accelerated viral infectivity similar to COVID. Sci Total Environ. 2020 Aug 10;729:138474. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138474. Epub 2020 Apr 20. PMID: 32498152; PMCID: PMC7169901.

Coccia M. How (Un)sustainable Environments are Related to the Diffusion of COVID-19: The Relation between Coronavirus Disease 2019, Air Pollution, Wind Resource and Energy. Sustainability. 2020; 12(22):9709. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229709

Coccia M. Comparative Critical Decisions in Management. In: Farazmand A, editor. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance. Springer Nature; 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_3969-1

Coccia M. The relation between length of lockdown, numbers of infected people and deaths of COVID-19, and economic growth of countries: Lessons learned to cope with future pandemics similar to COVID-19. Science of The Total Environment, 2021a; 775:145801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145801

Coccia M. Pandemic Prevention: Lessons from COVID-19. Encyclopedia. 2021b; 1:2; 433-444. doi: 10.3390/encyclopedia1020036

Coccia M. Different effects of lockdown on public health and economy of countries: Results from first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Economics Library. 2021c; 8(1):45-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jel.v8i1.2183

Coccia M. Recurring waves of Covid-19 pandemic with different effects in public health, Journal of Economics Bibliography. 2021d; 8:1; 28-45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jeb.v8i1.2184

Coccia M. High health expenditures and low exposure of population to air pollution as critical factors that can reduce fatality rate in COVID-19 pandemic crisis: a global analysis. Environ Res. 2021 Aug;199:111339. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111339. Epub 2021 May 21. PMID: 34029545; PMCID: PMC8139437.

Coccia M. How do low wind speeds and high levels of air pollution support the spread of COVID-19? Atmos Pollut Res. 2021 Jan;12(1):437-445. doi: 10.1016/j.apr.2020.10.002. Epub 2020 Oct 7. PMID: 33046960; PMCID: PMC7541047.

Coccia M. Evolution and structure of research fields driven by crises and environmental threats: the COVID-19 research. Scientometrics. 2021;126(12):9405-9429. doi: 10.1007/s11192-021-04172-x. Epub 2021 Oct 24. PMID: 34720251; PMCID: PMC8541882.

Coccia M. The impact of first and second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in society: comparative analysis to support control measures to cope with negative effects of future infectious diseases. Environ Res. 2021 Jun;197:111099. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111099. Epub 2021 Apr 2. PMID: 33819476; PMCID: PMC8017951.

Coccia M. Effects of human progress driven by technological change on physical and mental health, STUDI DI SOCIOLOGIA. 2021i; 2:113-132. https://doi.org/10.26350/000309_000116

Coccia M. Effects of the spread of COVID-19 on public health of polluted cities: results of the first wave for explaining the dejà vu in the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic and epidemics of future vital agents. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 Apr;28(15):19147-19154. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-11662-7. Epub 2021 Jan 4. PMID: 33398753; PMCID: PMC7781409.

Coccia M. Critical decisions for crisis management: An introduction. J. Adm. Soc. Sci. 2021m; 8:1; 1-14. http://dx.doi.org/10.1453/jsas.v8i1.2181

Coccia M. Meta-analysis to explain unknown causes of the origins of SARS-COV-2. Environ Res. 2022 Aug;211:113062. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113062. Epub 2022 Mar 5. PMID: 35259407; PMCID: PMC8897286.

Coccia M. COVID-19 Vaccination is not a Sufficient Public Policy to face Crisis Management of next Pandemic Threats. Public Organization Review. 2022a; 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-022-00661-6

Coccia M. Effects of strict containment policies on COVID-19 pandemic crisis: lessons to cope with next pandemic impacts. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Jan;30(1):2020-2028. doi: 10.1007/s11356-022-22024-w. Epub 2022 Aug 4. PMID: 35925462; PMCID: PMC9362501.

Coccia M. Improving preparedness for next pandemics: Max level of COVID-19 vaccinations without social impositions to design effective health policy and avoid flawed democracies. Environ Res. 2022 Oct;213:113566. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.113566. Epub 2022 May 31. PMID: 35660409; PMCID: PMC9155186.

Coccia M. Optimal levels of vaccination to reduce COVID-19 infected individuals and deaths: A global analysis. Environ Res. 2022 Mar;204(Pt C):112314. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.112314. Epub 2021 Nov 2. PMID: 34736923; PMCID: PMC8560189.

Coccia M. Preparedness of countries to face COVID-19 pandemic crisis: Strategic positioning and factors supporting effective strategies of prevention of pandemic threats. Environ Res. 2022 Jan;203:111678. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111678. Epub 2021 Jul 16. PMID: 34280421; PMCID: PMC8284056.

Coccia M. COVID-19 pandemic over 2020 (withlockdowns) and 2021 (with vaccinations): similar effects for seasonality and environmental factors. Environ Res. 2022 May 15;208:112711. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2022.112711. Epub 2022 Jan 13. PMID: 35033552; PMCID: PMC8757643.

Coccia M. The Spread of the Novel Coronavirus Disease-2019 in Polluted Cities: Environmental and Demographic Factors to Control for the Prevention of Future Pandemic Diseases. In: Faghih N, Forouharfar A. (eds) Socioeconomic Dynamics of the COVID-19 Crisis. Contributions to Economics: Springer, Cham. 2022g; 351-369. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-89996-7_16

Coccia M. Sources, diffusion and prediction in COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned to face next health emergency. AIMS Public Health. 2023 Mar 2;10(1):145-168. doi: 10.3934/publichealth.2023012. PMID: 37063362; PMCID: PMC10091135.

Coccia M, Benati I. Comparative Evaluation Systems, A. Farazmand (ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1210-1

Coccia M, Benati I. Comparative Studies. Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance –section Bureaucracy (edited by Ali Farazmand). Springer, Cham. 2018a; Chapter No. 1197-1:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31816-5_1197-1

Coccia M, Benati I. Effective health systems facing pandemic crisis: lessons from COVID-19 in Europe for next emergencies, International Journal of Health Governance. 2024a. DOI 10.1108/IJHG-02-2024-0013

Núñez-Delgado A, Bontempi E, Zhou Y, Álvarez-Rodríguez E, López-Ramón MV, Coccia M, Zhang Z, Santás-Miguel V, Race M. Editorial of the Topic “Environmental and Health Issues and Solutions for Anticoccidials and other Emerging Pollutants of Special Concern”. Processes. 2024; 12(7):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr12071379