Lifestyle and Well-being among Portuguese Firefighters

Emergency Medicine TraumaRehabilitation受け取った 18 Jan 2021 受け入れられた 06 Feb 2024 オンラインで公開された 07 Feb 2024

Focusing on Biology, Medicine and Engineering ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Previous Full Text

The Kazakh Language Requires Reform of its Writing

受け取った 18 Jan 2021 受け入れられた 06 Feb 2024 オンラインで公開された 07 Feb 2024

Background: Firefighters are subject to a variety of stressors, hence the importance of equipping them with resources that contribute to the management of these stressors.

Aims: Considering that a healthy lifestyle is one of these resources, this study aimed to characterize the lifestyle of a Portuguese firefighters sample, rate their general lifestyle level, and analyze its association with their subjective well-being (i.e., flourishing).

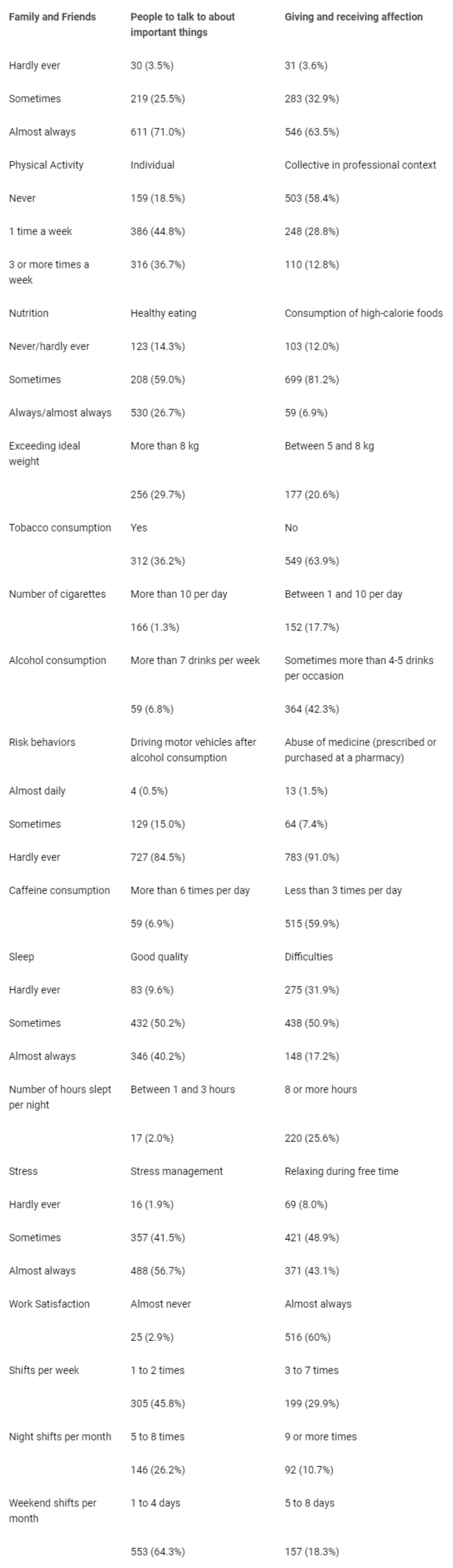

Methods: A sample of 860 firefighters responded to an adapted version of the FANTASTIC.

Results: The results showed that most (72.8%) had a good lifestyle. However, regarding each habit, a significant percentage had bad habits: sometimes consuming high-calorie foods (81.2%); sometimes having difficulties sleeping (50.9%); drinking more than 4 - 5 alcoholic drinks on the same occasion (43.9%); and exceeding their ideal weight by more than 8 kg (29.7%). However, a marked percentage also had healthy habits: having people to talk to (71%) and giving and receiving affection (63.5%); exercising at least once a week (81.5%); not smoking (63.9%); almost always eating healthily (26.7%); sometimes sleeping well (50.2%); and managing stress (56.7%). As expected, the assumption that firefighters’ lifestyle is related to their flourishing was supported.

Conclusion: A healthy lifestyle is an important resource to ensure the firefighters’ flourishing and should be a part of the day-to-day life of these professionals.

Firefighting is one of the most widely acknowledged dangerous jobs []. Firefighters work in high-risk environments that expose them to unpredictability and danger [], experiencing many job demands and stressors (e.g., physical demands; time pressure; work overload; role conflict; exposure to trauma, danger, and/or threats, etc.) [], that may lead to high stress and low well-being []. Subjective well-being is a broad, multidimensional concept, defined as a pleasant emotional experience, that: resides within an individual/subjective experience; includes positive effects and the absence of negative effects; involves a global positive assessment of the individual’s life []. Flourishing is a subjective well-being indicator referring to the existence of meaning and purpose in life, positive relationships, self-esteem, feelings of competence, optimism, and involvement in daily activities []. In the context of firefighting, some experiences should contribute to flourishing: seeing their role as essential in protecting lives and property; having strong and positive relationships with their colleagues, with a supportive and cohesive team environment; having confidence in their abilities and skills and feeling accomplishment in successfully handling challenging situations; maintaining a positive outlook even in the face of adversity, believing that their efforts contribute to positive outcomes; actively engaging in their daily duties.

To prepare firefighters to effectively manage the challenging situations that are a part of their daily lives and ensure their well-being, it is essential to provide resources that allow them to cope with the demands inherent to this profession [], namely contextual conditions (e.g., transformational leadership; []) and individual characteristics (e.g., healthy lifestyle habits).

Based on the Conservation of Resources Theory (COR, []), the adoption of healthy lifestyle habits by firefighters is crucial to equip them with personal resources that preserve and replenish their other personal and job resources, promoting their ability to cope with job demands and, consequently, increase their subjective well-being. For example, sleep quality [], a healthy diet [], and physical activity [] boost the resources that promote well-being. Relationships with family and friends, and providing emotional support, are also essential resources to help firefighters deal with their job demands and ensure well-being []. Moreover, the non-consumption of alcohol and tobacco is beneficial to preserve firefighters’ resources since these addictions can deplete resources and compromise physical and mental health [].

The contribution of healthy lifestyle habits to well-being among the general population has been highlighted, notably by a literature review []. However, little is known about the impact of the healthy lifestyle of firefighters on their subjective well-being.

According to the COR theory [], individuals seek to obtain, retain, and protect the resources (objects; personal characteristics; physical, psychological, and social conditions) that enable them to achieve their goals, and subjective well-being is threatened when they lose, risk losing, or invest too many resources compared to those they manage to obtain. However, when individuals have access to the resources needed to deal with the loss or threat of loss of resources inherent to stressors, their subjective well-being is ensured []. Thus, a healthy lifestyle may be an asset to firefighters as it provides access to further resources that are essential to ensure their subjective well-being when confronted with stressful situations [].

Previous research among firefighters has shown that well-being is affected by lifestyle behaviors and habits such as sleep [], physical activity [], body mass index [-], smoking cessation [], weight management [] and alcohol consumption []. Furthermore, an intervention program to promote healthy lifestyle habits in firefighters proved to be effective in improving firefighters’ well-being [].

The aim of this study was threefold: to provide a characterization of each of the lifestyle habits of a Portuguese firefighters’ sample; to rate their general lifestyle in an integrated manner; and to assess the association between the lifestyle and flourishing. The characterization of the lifestyle in an integrated manner was achieved through the examination of various lifestyle behaviors and habits, namely the relationship with family and friends, the physical activity, the dietary habits, the body mass index, the alcohol and tobacco consumption, the sleep quality, the stress management, the career, and shifts. In the association between lifestyle and flourishing, was hypothesized that firefighters with a better lifestyle were those that had higher flourishing.

This study offers several contributions. First, prior research [,] has evaluated the relationship between a few firefighters’ lifestyle behaviors or habits and their well-being, whereas, in this study, the effect of different lifestyle behaviors and habits has been evaluated in an integrated manner, using an adapted version of the FANTASTIC questionnaire (original questionnaire: []). This questionnaire has been employed to characterize the lifestyle of diabetic patients [], seniors [], middle-aged adults [], and university students [], but, to our knowledge, this is the first study employing an adapted version of the FANTASTIC to the firefighter population. Second, previous studies [,,] have used the absence of illness (e.g., depression) or specific measures (e.g., life satisfaction, work engagement) as indicators of well-being, whereas in this study, flourishing, a construct that allows for a broad and multiple dimension view of subjective well-being, has been used as a well-being indicator. Finally, although there are studies characterizing the lifestyle habits of firefighters in other countries (e.g., [,]), no study has characterized the lifestyle habits of Portuguese firefighters. This study sought to fill this gap as these professionals have experienced many challenges, with Portugal being the southern European country that is most affected by rural fires [], which are highly stressful situations that require firefighters’ access to as many resources as possible to deal with them.

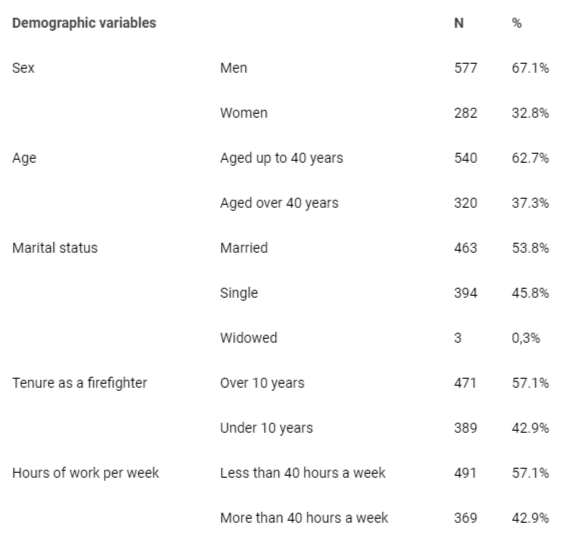

The National School of Firefighters sent an email to all fire commanders of Portuguese corporations, asking them to disseminate the questionnaire among firefighters of his/her corporation. All firefighters who agreed to participate read an informed consent and answered an online questionnaire through the Qualtrics platform. Answers to the questionnaire were collected from April 24th to May 27th, 2021. Anonymity and confidentiality were assured, and approval was granted by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon (Ref RAPI_2021428mjc; May 20th, 2021) (Table 1).

The firefighters’ lifestyle was measured with an adaptation of the FANTASTIC []. The original scale comprises 25 questions that explore 9 domains identified with the acronym FANTASTIC: Family and friends, physical Activity, Nutrition, Tobacco, Alcohol and other drugs, Sleep/stress, Type of personality, Insight, and Career. A pre-test was conducted, and the dimensions Type of personality and Insight were removed since they were deemed inappropriate by the firefighters in the focus group who reported that, when on duty, a firefighter cannot feel “angry or hostile” or “sad or depressed” (statements in these dimensions). Thus, the following dimensions were evaluated:

Family and friends - 2 questions (e.g., “I have someone to talk to about matters that are important to me”; answered on a scale of 1 to 3, where 1 means “Hardly ever” and 3 means “Almost always”).

Physical Activity - 2 questions (e.g., “I personally practice physical activity or sport for at least 30 minutes at a time”; answered on a scale of 1 to 3, where 1 means “I do nothing” and 3 means “3 or more times a week”).

Nutrition - 3 questions (e.g., “I eat a balanced diet and eat 3 to 5 servings of fruits and vegetables a day”; answered on a scale of 1 to 3, where 1 means “Hardly ever” and 3 means “Everyday”).

Tobacco - 2 questions (e.g., “I smoke cigarettes”; answered on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means “Yes” and 5 means “No, I never smoked”).

Alcohol and other drugs - 5 questions (e.g., “My weekly intake of alcoholic beverages is”; answered on a scale of 1 to 3, where 1 means “More than 12 drinks” and 3 means “0 to 7 drinks”).

Sleep/stress - 5 questions (e.g., “I sleep well and feel rested”; answered on a scale of 1 to 3, where 1 means “Hardly ever” and 3 means “Almost always”).

Career and Shifts - 4 questions (e.g., “I am satisfied with the work in general and with the functions I perform in the Fire Department”; answered on a scale of 1 to 3, where 1 means “Hardly ever” and 3 means “Almost always”). The original questionnaire [] only has one Career question, but we included other three questions about Shifts (“Do you work shifts?”, “Do the shifts you work include working between 00:00 and 8:00 in the morning?” and “On average, how many weekend days do you usually work per month?”) because this variable has shown to be crucial in explaining the well-being of firefighters (e.g., []).

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.680, like other studies using the FANTASTIC Questionnaire []. The sum of the questions produces a global score for each participant, ranging from 0 to 76 points (0 - 26 needs improvement; 27-41 fair; 42-52 good; 53-64 very good; 65-76 excellent).

Firefighters’ flourishing was measured with the Portuguese version [] of Diener’s Flourishing Scale [], which includes 8 statements (e.g., “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life.”; “I actively contribute to the happiness and well-being of others.”) answered on a 7-point scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), where a higher score is indicative of higher flourishing (Cronbach’s alpha = .83).

Sex (1 = male; 0 = female), age (year of birth), marital status (1 = married; 0 = single separated, widowed), number of years as a firefighter (1 = less than a year; 2 = from 1 to 5 years; 3 = from 5 to 10 years; 4 = more than 10 years) and the average number of hours worked per week were inserted as control variables.

Data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 27). Table 2 presents the results of the participants’ lifestyle habits (number of participants in each response category and the respective percentage).

The results of the global score (sum of the questions) of Lifestyle were as follows: 1 participant (0.1%) needs improvement; 139 participants (16.1%) show fair lifestyle; 626 participants (72.8%) show good lifestyle; 94 participants (10.8%) show very good lifestyle and 0 participants show excellent lifestyle.

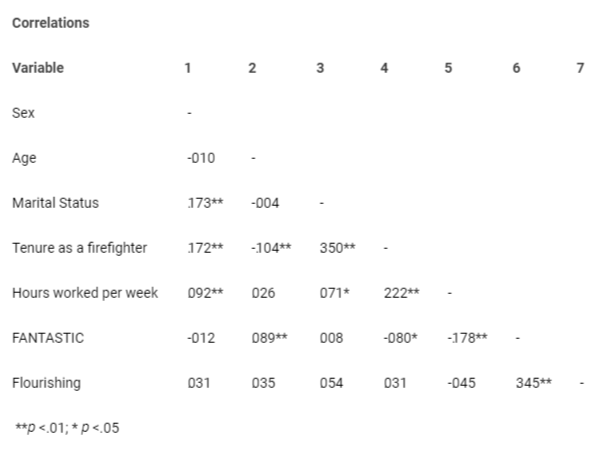

First, to examine the association between variables, correlations were performed (Cf. Table 3).

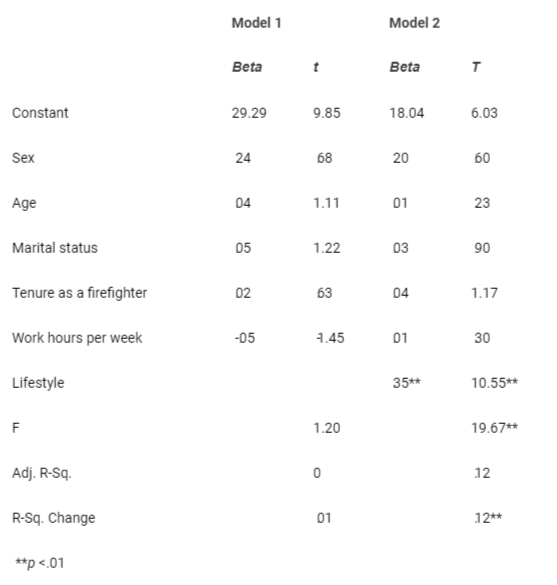

Afterward, to infer the relationship between the independent variable (Lifestyle) and the dependent variable (Flourishing), a hierarchical regression was performed (cf. Table 4). Control variables were inserted in the first step and the lifestyle was inserted in the second step. A positive and significant relationship between lifestyle and flourishing is observed (β = .35, p < .01; Table 4), supporting the hypothesis that the firefighters with a better lifestyle as those that have higher flourishing.

The aim of this study was to characterize each of the lifestyle habits of a Portuguese firefighters sample, to rate their general lifestyle level, and to analyze the effect of the lifestyle on their flourishing.

In terms of the adoption of healthy lifestyle habits, these firefighters were less compliant than firefighters from other countries or regions regarding physical activity, nutrition, tobacco, and alcohol consumption. However, a healthy pattern was observed regarding the social relationships, quality of sleep, and stress management of this Portuguese firefighters’ sample. Regardingphysical activity, the firefighters revealed low levels of physical activity practice (only 36.7% engaged in physical activity three or more times a week) and exercised less per week than firefighters from a study with 40 USA firefighters (where approximately 90% exercised during their leisure time). This result is concerning as exercise can have positive effects on health outcomes and fitness and is associated with high performance and reduced risks of injury in firefighters [].

Regarding nutrition, 29.8% of the firefighters were observed to exceed their ideal weight by more than 8 kg. This result is in line with a study [] with 3172 career firefighters from the USA and Canada that found that more than 80% of the participants were in overweight or obese BMI categories. These negative findings may possibly be explained by the fact that since firefighters are exposed to high-risk and stressful situations [] they might eat more food in general and, specifically, more junk food, in response to stress []. However, our sample reported better dietary habits (i.e., more than a quarter reported always/almost always eating healthily, and more than half reported eating healthily sometimes) than a sample of firefighters from the USA [], where 90% consumed fast food 1 to 3 times per week.

Concerning tobacco consumption, the prevalence (36.2%) was higher than in studies of other countries. A study with 157 firefighters from the USA observed that only 7% of the participants consumed tobacco on a daily basis []; a study with 711 firefighters from Brazil observed a prevalence of 7.6% of tobacco consumption, with 9.8% of the respondents being former smokers []. One possible explanation is the fact that in Portugal tobacco consumption is a common coping mechanism for stress [].

Concerning alcohol consumption, 43.9% of the firefighters drank more than 4 - 5 alcoholic drinks on the same occasion. This result is in line with two studies from the USA: one with 954 career firefighters, where almost half of the sample reported drinking more than 4 - 5 alcoholic drinks on the same day [], and other with 166 career firefighters, where 34% drank more than 4 - 5 drinks on one occasion []. A possible explanation is that the firefighters´ context has a culture of drinking [], and alcohol consumption has been reported to be a prevalent coping mechanism among these professionals [].

However, a healthy pattern was observed in some of the Portuguese firefighters’ lifestyle habits. Regarding social relationships, most reported almost always having people to talk to about important issues and almost always giving and receiving affection, which is particularly important given the strong evidence of the buffering effects of social support in this high-stress, high-risk occupation [], where professionals must rely on their coworkers, family, and friends for social support to cope with the dangerous and stressful demands inherent to their careers []. These professionals were also observed to have an adequate quality of sleep (only 9.6% hardly ever sleep well) and better than that found in a recent study with 193 French firefighters, where 26.9% reported sleeping poorly []. One possible explanation is that the two countries may have different job schedules, demands, and stressors. As far as stress management is concerned, these Portuguese firefighters reported adequate skills: the majority were frequently able to manage their stress and relax during their free time, an important finding as these skills are essential in a profession where many stressful situations are encountered daily [].

The general lifestyle level of this Portuguese firefighters’ sample was found to be mainly good (72.8%). This is in line with a study using FANTASTIC with diabetic patients that observed mainly good and very good lifestyle levels []. However, other studies reported better results: a study with Polish seniors showed excellent (45.7%) or very good (41.3%) lifestyle levels, with none of the respondents scoring in the lowest category []; a study with Colombian middle-aged adults showed a very good (55.7%) lifestyle level []; a study with Colombian adults showed very good (47%) or excellent (47%) lifestyle level []; a study with Colombian university students observed mainly a very good (57.8%) lifestyle level [Ramírez-Vélez2015]. One possible explanation may be that firefighting is characterized by high demands (e.g., acting in situations with high emotional and physical demands and posing danger to life) that compromise the desire to adopt a healthy lifestyle [,].

As expected, firefighters’ healthy lifestyle is related to their flourishing, meaning that the better the firefighters’ lifestyle level, the better their purpose in life, positive relationships, self-esteem, feelings of competence, optimism, and involvement in daily activities. This result supports the COR assumption that a healthy lifestyle may be a resource that enables access to further resources that may be used by firefighters to deal with stressful situations and maintain their levels of well-being [] and is in line with the results of previous studies with firefighters [,].

This study presents some limitations. First, the sample was not representative of the Portuguese firefighter population (26123 in 2021; []) and the percentage of females who responded to the questionnaire (32.8%) may not reflect the female firefighter population (22% in 2020; []). Moreover, those who chose to respond to the questionnaire may have characteristics that differ from those who chose not to respond (e.g., individuals who prioritize their lifestyle may be more likely to participate, while those who do not may be less likely to engage with the study, which may result in a biased sample towards more health conscious firefighters). Thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. Future studies should address selection bias and take steps toward obtaining a representative sample.

Second, despite the participants’ anonymity, the responses may have been influenced by social desirability. Future studies could complement questionnaires with observations and objective (e.g., medical records) data, providing a more accurate and complete picture of the firefighters’ lifestyle and subjective well-being. It would also be interesting for future studies to evaluate changes in lifestyle and verify their role in promoting well-being.

Third, in Portugal, there is no differentiation between wildland and structural firefighters, both work alongside volunteer firefighters, in the same corporations. All the firefighters intervene in different emergency situations (rural and urban fires, accidents, etc.), even though there are teams for specific emergency situations (i.e., in the summer for rural fires, all year round for permanent action) in each corporation. In this study, information on the number and severity of emergencies in which the participants acted or their involvement in these emergency teams was not collected. Future studies could be developed with specific intervention teams who face especially stressful situations that can influence their lifestyle and subjective well-being.

Fourth, the instrument was adapted with two dimensions considered inadequate in this context removed, and three questions were added in one dimension, which may have altered its psychometric properties. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution.

These results have an important theoretical implication for understanding the relationship between firefighters’ lifestyle and their subjective well-being, supporting the COR assumption that resources (i.e., healthy lifestyle) are crucial to ensure the subjective well-being (i.e. flourishing) of professionals who face stressful demands [].

This study also presents practical implications for firefighters’ management, namely to equip them to face the daily highly demanding and stressful situations without compromising their subjective well-being. A culture that places value on firefighters’ healthy habits needs to be instilled. In fact, firefighters describe the fire service lifestyle as a challenge to making improvements in diet and exercise, emphasizing the importance of leaders’ support for health and wellness programs to obtain buy-in from firefighters []. This means that leaders need to be encouraged to develop practices that promote healthy habits and adopt behavior that sets an example for the team members. Examples of those practices may be training on nutrition or sleep, the establishment of a daily timeslot for physical activity; providing electric grills to facilitate healthy cooking, scales to promote weight awareness, and healthy snack alternatives to the processed foods available []. These strategies must be adapted to the idiosyncrasies of the corporations and some cultural and operational characteristics (e.g., shift work, combination of professionals and volunteers) must be considered so that these strategies can be successfully implemented.

The firefighters’ lifestyle is related to their flourishing. Considering the limitations of this study, future studies could: address selection bias and take steps towards obtaining a representative sample; complement questionnaires with observations and objective data; evaluate changes in lifestyle and verify the effect on well-being; and evaluate specific intervention teams who face especially stressful situations. Improving firefighters’ healthy lifestyle habits might be important to improve firefighters’ subjective well-being. It is important to explore strategies to promote healthy lifestyle habits among firefighters, such as education and training programs, workplace wellness initiatives, and policies to support healthy lifestyle habits.

Firefighters are subject to many stressors, hence the importance of equipping them with resources (e.g., healthy lifestyle) to manage the stressors. This study characterized the lifestyle habits of a Portuguese firefighters sample, rated their general lifestyle level, and analyzed its association with their subjective well-being (i.e., flourishing). 860 firefighters responded to an adapted version of the FANTASTIC. Most had a good lifestyle. Firefighters’ lifestyle is related to their flourishing; thus, lifestyle is an important resource to ensure the firefighters’ well-being.

Conceptualization, L.C., and M.J.C.; methodology, L.C, and R.P.; validation, L.C., R.P., J.F-A., S.N., and M.J.C; formal analysis, L.C.; investigation, L.C., and R.P.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, L.C., R.P., J.F-A., S.N. and M.J.C.; supervision, M.J.C.; funding acquisition, M.J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

This research was funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia [Foundation for Science and Technology], under grant number PCIF/SSO/0054/2018.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conduc-ted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon (Ref RAPI_2021428mjc; May 20th, 2021).

This work is an investigation integrated with the Project PCIF/SSO/0054/2018 Leadership Process and Firefighters Occupational Health: Development of an intervention program.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Corneil W, Beaton R, Murphy S, Johnson C, Pike K. Exposure to traumatic incidents and prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in urban firefighters in two countries. J Occup Health Psychol. 1999 Apr;4(2):131-41. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.2.131. PMID: 10212865.

O’Neill OA, Rothbard NP. Is love all you need? The effects of emotional culture, suppression, and work-family conflict on firefighter risk-taking and health. Acad Manage J. 2017; 60(1):78-108.

DeJoy DM, Smith TD, Dyal MA. Safety climate and firefighting: Focus group results. J Safety Res. 2017 Sep; 62:107-116. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2017.06.011. Epub 2017 Jun 23. PMID: 28882257.

Airila A. Work characteristics, personal resources, and employee well-being: A longitudinal study among Finnish firefighters. Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, People and Work Research Reports. 2015; 109.

Diener E. The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. New York: Springer. 2009; 37:11-58

Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi DW, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Indic. Res. 2010; 97(2):143-156.

Hobfoll SE. Social and psychological resources and adaptation.Rev Gen Psychol. 2002; 6(4):307-324.

Maio A, Chambel MJ, Carmona L. Transformational leadership and flourishing in Portuguese professional firefighters: The moderating role of the frequency of intervention in rural fires. Front Psychol. 2023 Feb 13; 14:1076411. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1076411. PMID: 36860783; PMCID: PMC9970159.

Gothe NP, Ehlers DK, Salerno EA, Fanning J, Kramer AF, McAuley E. Physical Activity, Sleep and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Influence of Physical, Mental and Social Well-being. Behav Sleep Med. 2020 Nov-Dec;18(6):797-808. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2019.1690493. Epub 2019 Nov 12. PMID: 31713442; PMCID: PMC7324024.

Muscaritoli M. The Impact of Nutrients on Mental Health and Well-Being: Insights from the Literature. Front Nutr. 2021 Mar 8; 8:656290. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.656290. PMID: 33763446; PMCID: PMC7982519.

Buecker S, Simacek T, Ingwersen B, Terwiel S, Simonsmeier BA. Physical activity and subjective well-being in healthy individuals: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2021 Dec;15(4):574-592. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2020.1760728. Epub 2020 Jun 10. PMID: 32452716.

Cipolletta S, Mercurio A, Pezzetta R. Perceived social support and well-being of international students at an Italian university. Int. Stud. 2022;12(3):613-632.

Althobaiti YS, Alzahrani MA, Alsharif NA, Alrobaie NS, Alsaab HO, Uddin MN. The Possible Relationship between the Abuse of Tobacco, Opioid, or Alcohol with COVID-19. Healthcare (Basel). 2020 Dec 22;9(1):2. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010002. PMID: 33375144; PMCID: PMC7822153.

Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;18(2):189-93. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013. PMID: 16639173.

Siddall A, Turner P, Stevenson R, Standage M, Bilzon J. Lifestyle behaviors, well-being and chronic disease biomarkers in UK operational firefighters. In 61st Annual Meeting of American College of Sports Medicine, 2014; 27.

Demos A. Impact of the firefighter academy on recruits' general well-being and distress. UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2007; 2285. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/4828-vedk

Turner P, Siddall A, Stevenson R, Standage M, Bilzon J. Lifestyle and Well-being in High Cardiovascular Disease Risk Groups in the UK Fire & Rescue Service. In Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 530 Walnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19106-3621 USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2014; 46:5; 931-931)

Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Kuehl KS, Moe EL, Breger RK, Pickering MA. The PHLAME (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models' Effects) firefighter study: outcomes of two models of behavior change. J Occup Environ Med. 2007 Feb;49(2):204-13. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3180329a8d. PMID: 17293760.

Andrews KL, Gallagher S, Herring MP. The effects of exercise interventions on health and fitness of firefighters: A meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019 Jun;29(6):780-790. doi: 10.1111/sms.13411. Epub 2019 Mar 10. PMID: 30779389.

Haddock CK, Day RS, Poston WS, Jahnke SA, Jitnarin N. Alcohol use and caloric intake from alcohol in a national cohort of U.S. career firefighters. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015 May;76(3):360-6. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.360. PMID: 25978821.

Wilson D, Ciliska D. Lifestyle assessment: Development and use of the FANTASTIC Checklist. Can Fam Physician. 1984; 30:1527-1532.

Rodríguez-Moctezuma J, López-Carmona J, Munguía-Miranda C, Hernández-Santiago J, Martinez-Bermúdez M. Validez y consistencia del instrumento FANTASTIC para medir estilo de vida en diabéticos. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2003; 41: 211–220.

Deluga A, Kosicka B, Dobrowolska B, Chrzan-Rodak A, Jurek K, Wrońska I, Ksykiewicz-Dorota A, Jędrych M, Drop B. Lifestyle of the elderly living in rural and urban areas measured by the FANTASTIC Life Inventory. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2018 Sep 25;25(3):562-567. doi: 10.26444/aaem/86459. Epub 2018 Apr 4. PMID: 30260173.

Triviño-Quintero L, Dosman-González V, Uribe-Vélez Y, Agredo-Zuñiga R. A study of lifestyle and its relationship with risk factors for metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults. Acta Med. Colomb. 2009; 34:158–163.

Ramírez-Vélez R, Triana-Reina HR, Carrillo HA, Ramos-Sepúlveda JA, Rubio F, Poches-Franco L, Rincón-Párraga D, Meneses-Echávez JF, Correa-Bautista JE. A cross-sectional study of Colombian University students' self-perceived lifestyle. Springerplus. 2015 Jun 24; 4:289. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1043-2. PMID: 26120506; PMCID: PMC4478172.

Lourenço L. Forest fires in continental Portugal Result of profound alterations in society and territorial consequences. Méditerranée. Revue géographique des pays méditerranéens/Journal of Mediterranean geography. 2018; 130.

Halbesleben JR. The influence of shift work on emotional exhaustion in firefighters: The role of work‐family conflict and social support. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2009; 2(2):115-130.

Silva AJ, Caetano A. Validation of the flourishing scale and scale of positive and negative experience in Portugal.Indic. Res. 2013; 110(2):469-478.

Yang J, Farioli A, Korre M, Kales SN. Dietary Preferences and Nutritional Information Needs Among Career Firefighters in the United States. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015 Jul;4(4):16-23. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2015.050. PMID: 26331100; PMCID: PMC4533657.

Leung SL, Barber JA, Burger A, Barnes RD. Factors associated with healthy and unhealthy workplace eating behaviours in individuals with overweight/obesity with and without binge eating disorder. Obes Sci Pract. 2018 Feb 14;4(2):109-118. doi: 10.1002/osp4.151. PMID: 29670748; PMCID: PMC5893464.

Eastlake AC, Knipper BS, He X, Alexander BM, Davis KG. Lifestyle and safety practices of firefighters and their relation to cardiovascular risk factors. Work. 2015 Jan 1;50(2):285-94. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131796. PMID: 24284685.

Lima Ede P, Assuncao AA, Barreto SM. Tabagismo e estressores ocupacionais em bombeiros, 2011 [Smoking and occupational stressors in firefighters, 2011]. Rev Saude Publica. 2013 Oct;47(5):897-904. Portuguese. doi: 10.1590/s0034-8910.2013047004674. PMID: 24626494.

Lawless MH, Harrison KA, Grandits GA, Eberly LE, Allen SS. Perceived stress and smoking-related behaviors and symptomatology in male and female smokers. Addict Behav. 2015 Dec; 51:80-3. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.011. Epub 2015 Jul 26. PMID: 26240941; PMCID: PMC4558262.

Piazza-Gardner AK, Barry AE, Chaney E, Dodd V, Weiler R, Delisle A. Covariates of alcohol consumption among career firefighters. Occup Med (Lond). 2014 Dec;64(8):580-2. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu124. Epub 2014 Aug 22. PMID: 25149118.

Haddock CK, Jitnarin N, Caetano R, Jahnke SA, Hollerbach BS, Kaipust CM, Poston WSC. Norms about Alcohol Use among US Firefighters. Saf Health Work. 2022 Dec;13(4):387-393. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2022.08.008. Epub 2022 Sep 21. PMID: 36579011; PMCID: PMC9772477.

Smith LJ, Gallagher MW, Tran JK, Vujanovic AA. Posttraumatic stress, alcohol use, and alcohol use reasons in firefighters: The role of sleep disturbance. Compr Psychiatry. 2018 Nov; 87:64-71. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.09.001. Epub 2018 Sep 7. PMID: 30219373.

Regehr C. Social support as a mediator of psychological distress in firefighters. J. Psychol. 2009; 30(1-2):87-98.

Savall A, Marcoux P, Charles R, Trombert B, Roche F, Berger M. Sleep quality and sleep disturbances among volunteer and professional French firefighters: FIRESLEEP study. Sleep Med. 2021 Apr; 80:228-235. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.01.041. Epub 2021 Feb 2. PMID: 33610069.

Ramírez-Vélez R, Agredo RA. Fiabilidad y validez del instrumento "Fantástico" para medir el estilo de vida en adultos colombianos [The Fantastic instrument's validity and reliability for measuring Colombian adults' life-style]. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota). 2012 Mar-Apr;14(2):226-37. Spanish. doi: 10.1590/s0124-00642012000200004. PMID: 23250366.

Número de bombeiros. April 14th 2023. 2022. https://www.pordata.pt/portugal/numero+de+bombeiros-1188

Portuguese General Secretariat Ministry of Internal Administration. Mulheres Mai(s). https://www.sg.mai.gov.pt/Documents/MulheresMAI_VF_08_03_2021.pdf

Frattaroli S, Pollack KM, Bailey M, Schafer H, Cheskin LJ, Holtgrave DR. Working inside the firehouse: developing a participant-driven intervention to enhance health-promoting behaviors. Health Promot Pract. 2013 May;14(3):451-8. doi: 10.1177/1524839912461150. Epub 2012 Oct 22. PMID: 23091304.

Carmona L, Pinheiro R, Faria-Anjos J, Namorado S, Chambel MA. Lifestyle and Well-being among Portuguese Firefighters. IgMin Res. 07 Feb, 2024; 2(2): 059-065. IgMin ID: igmin146; DOI: 10.61927/igmin146; Available at: www.igminresearch.com/articles/pdf/igmin146.pdf

次のリンクを共有した人は、このコンテンツを読むことができます:

1CicPsi, Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon, Portugal

2National Fire Service School, Portugal

3National Institute of Medical Emergency, Portuga

4Department of Epidemiology, National Institute of Health Dr. Ricardo Jorge, Portugal

Address Correspondence:

Laura Carmona, CicPsi, Faculty of Psychology, University of Lisbon, Portugal, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Carmona L, Pinheiro R, Faria-Anjos J, Namorado S, Chambel MA. Lifestyle and Well-being among Portuguese Firefighters. IgMin Res. 07 Feb, 2024; 2(2): 059-065. IgMin ID: igmin146; DOI: 10.61927/igmin146; Available at: www.igminresearch.com/articles/pdf/igmin146.pdf

Copyright: © 2024 Carmona L, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Table 1: Characteristics of the sample....

Table 1: Characteristics of the sample....

Table 2: Participants’ lifestyle habits....

Table 2: Participants’ lifestyle habits....

Table 3: Correlations between variables....

Table 3: Correlations between variables....

Table 4: Hierarchical Regression of Firefighters’ Lif...

Table 4: Hierarchical Regression of Firefighters’ Lif...

Corneil W, Beaton R, Murphy S, Johnson C, Pike K. Exposure to traumatic incidents and prevalence of posttraumatic stress symptomatology in urban firefighters in two countries. J Occup Health Psychol. 1999 Apr;4(2):131-41. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.2.131. PMID: 10212865.

O’Neill OA, Rothbard NP. Is love all you need? The effects of emotional culture, suppression, and work-family conflict on firefighter risk-taking and health. Acad Manage J. 2017; 60(1):78-108.

DeJoy DM, Smith TD, Dyal MA. Safety climate and firefighting: Focus group results. J Safety Res. 2017 Sep; 62:107-116. doi: 10.1016/j.jsr.2017.06.011. Epub 2017 Jun 23. PMID: 28882257.

Airila A. Work characteristics, personal resources, and employee well-being: A longitudinal study among Finnish firefighters. Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, People and Work Research Reports. 2015; 109.

Diener E. The science of well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. New York: Springer. 2009; 37:11-58

Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi DW, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Indic. Res. 2010; 97(2):143-156.

Hobfoll SE. Social and psychological resources and adaptation.Rev Gen Psychol. 2002; 6(4):307-324.

Maio A, Chambel MJ, Carmona L. Transformational leadership and flourishing in Portuguese professional firefighters: The moderating role of the frequency of intervention in rural fires. Front Psychol. 2023 Feb 13; 14:1076411. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1076411. PMID: 36860783; PMCID: PMC9970159.

Gothe NP, Ehlers DK, Salerno EA, Fanning J, Kramer AF, McAuley E. Physical Activity, Sleep and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Influence of Physical, Mental and Social Well-being. Behav Sleep Med. 2020 Nov-Dec;18(6):797-808. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2019.1690493. Epub 2019 Nov 12. PMID: 31713442; PMCID: PMC7324024.

Muscaritoli M. The Impact of Nutrients on Mental Health and Well-Being: Insights from the Literature. Front Nutr. 2021 Mar 8; 8:656290. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.656290. PMID: 33763446; PMCID: PMC7982519.

Buecker S, Simacek T, Ingwersen B, Terwiel S, Simonsmeier BA. Physical activity and subjective well-being in healthy individuals: a meta-analytic review. Health Psychol Rev. 2021 Dec;15(4):574-592. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2020.1760728. Epub 2020 Jun 10. PMID: 32452716.

Cipolletta S, Mercurio A, Pezzetta R. Perceived social support and well-being of international students at an Italian university. Int. Stud. 2022;12(3):613-632.

Althobaiti YS, Alzahrani MA, Alsharif NA, Alrobaie NS, Alsaab HO, Uddin MN. The Possible Relationship between the Abuse of Tobacco, Opioid, or Alcohol with COVID-19. Healthcare (Basel). 2020 Dec 22;9(1):2. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010002. PMID: 33375144; PMCID: PMC7822153.

Penedo FJ, Dahn JR. Exercise and well-being: a review of mental and physical health benefits associated with physical activity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2005 Mar;18(2):189-93. doi: 10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013. PMID: 16639173.

Siddall A, Turner P, Stevenson R, Standage M, Bilzon J. Lifestyle behaviors, well-being and chronic disease biomarkers in UK operational firefighters. In 61st Annual Meeting of American College of Sports Medicine, 2014; 27.

Demos A. Impact of the firefighter academy on recruits' general well-being and distress. UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2007; 2285. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/4828-vedk

Turner P, Siddall A, Stevenson R, Standage M, Bilzon J. Lifestyle and Well-being in High Cardiovascular Disease Risk Groups in the UK Fire & Rescue Service. In Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 530 Walnut St, Philadelphia, PA 19106-3621 USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2014; 46:5; 931-931)

Elliot DL, Goldberg L, Kuehl KS, Moe EL, Breger RK, Pickering MA. The PHLAME (Promoting Healthy Lifestyles: Alternative Models' Effects) firefighter study: outcomes of two models of behavior change. J Occup Environ Med. 2007 Feb;49(2):204-13. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3180329a8d. PMID: 17293760.

Andrews KL, Gallagher S, Herring MP. The effects of exercise interventions on health and fitness of firefighters: A meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2019 Jun;29(6):780-790. doi: 10.1111/sms.13411. Epub 2019 Mar 10. PMID: 30779389.

Haddock CK, Day RS, Poston WS, Jahnke SA, Jitnarin N. Alcohol use and caloric intake from alcohol in a national cohort of U.S. career firefighters. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2015 May;76(3):360-6. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.360. PMID: 25978821.

Wilson D, Ciliska D. Lifestyle assessment: Development and use of the FANTASTIC Checklist. Can Fam Physician. 1984; 30:1527-1532.

Rodríguez-Moctezuma J, López-Carmona J, Munguía-Miranda C, Hernández-Santiago J, Martinez-Bermúdez M. Validez y consistencia del instrumento FANTASTIC para medir estilo de vida en diabéticos. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2003; 41: 211–220.

Deluga A, Kosicka B, Dobrowolska B, Chrzan-Rodak A, Jurek K, Wrońska I, Ksykiewicz-Dorota A, Jędrych M, Drop B. Lifestyle of the elderly living in rural and urban areas measured by the FANTASTIC Life Inventory. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2018 Sep 25;25(3):562-567. doi: 10.26444/aaem/86459. Epub 2018 Apr 4. PMID: 30260173.

Triviño-Quintero L, Dosman-González V, Uribe-Vélez Y, Agredo-Zuñiga R. A study of lifestyle and its relationship with risk factors for metabolic syndrome in middle-aged adults. Acta Med. Colomb. 2009; 34:158–163.

Ramírez-Vélez R, Triana-Reina HR, Carrillo HA, Ramos-Sepúlveda JA, Rubio F, Poches-Franco L, Rincón-Párraga D, Meneses-Echávez JF, Correa-Bautista JE. A cross-sectional study of Colombian University students' self-perceived lifestyle. Springerplus. 2015 Jun 24; 4:289. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1043-2. PMID: 26120506; PMCID: PMC4478172.

Lourenço L. Forest fires in continental Portugal Result of profound alterations in society and territorial consequences. Méditerranée. Revue géographique des pays méditerranéens/Journal of Mediterranean geography. 2018; 130.

Halbesleben JR. The influence of shift work on emotional exhaustion in firefighters: The role of work‐family conflict and social support. Int J Workplace Health Manag. 2009; 2(2):115-130.

Silva AJ, Caetano A. Validation of the flourishing scale and scale of positive and negative experience in Portugal.Indic. Res. 2013; 110(2):469-478.

Yang J, Farioli A, Korre M, Kales SN. Dietary Preferences and Nutritional Information Needs Among Career Firefighters in the United States. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015 Jul;4(4):16-23. doi: 10.7453/gahmj.2015.050. PMID: 26331100; PMCID: PMC4533657.

Leung SL, Barber JA, Burger A, Barnes RD. Factors associated with healthy and unhealthy workplace eating behaviours in individuals with overweight/obesity with and without binge eating disorder. Obes Sci Pract. 2018 Feb 14;4(2):109-118. doi: 10.1002/osp4.151. PMID: 29670748; PMCID: PMC5893464.

Eastlake AC, Knipper BS, He X, Alexander BM, Davis KG. Lifestyle and safety practices of firefighters and their relation to cardiovascular risk factors. Work. 2015 Jan 1;50(2):285-94. doi: 10.3233/WOR-131796. PMID: 24284685.

Lima Ede P, Assuncao AA, Barreto SM. Tabagismo e estressores ocupacionais em bombeiros, 2011 [Smoking and occupational stressors in firefighters, 2011]. Rev Saude Publica. 2013 Oct;47(5):897-904. Portuguese. doi: 10.1590/s0034-8910.2013047004674. PMID: 24626494.

Lawless MH, Harrison KA, Grandits GA, Eberly LE, Allen SS. Perceived stress and smoking-related behaviors and symptomatology in male and female smokers. Addict Behav. 2015 Dec; 51:80-3. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.07.011. Epub 2015 Jul 26. PMID: 26240941; PMCID: PMC4558262.

Piazza-Gardner AK, Barry AE, Chaney E, Dodd V, Weiler R, Delisle A. Covariates of alcohol consumption among career firefighters. Occup Med (Lond). 2014 Dec;64(8):580-2. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqu124. Epub 2014 Aug 22. PMID: 25149118.

Haddock CK, Jitnarin N, Caetano R, Jahnke SA, Hollerbach BS, Kaipust CM, Poston WSC. Norms about Alcohol Use among US Firefighters. Saf Health Work. 2022 Dec;13(4):387-393. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2022.08.008. Epub 2022 Sep 21. PMID: 36579011; PMCID: PMC9772477.

Smith LJ, Gallagher MW, Tran JK, Vujanovic AA. Posttraumatic stress, alcohol use, and alcohol use reasons in firefighters: The role of sleep disturbance. Compr Psychiatry. 2018 Nov; 87:64-71. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.09.001. Epub 2018 Sep 7. PMID: 30219373.

Regehr C. Social support as a mediator of psychological distress in firefighters. J. Psychol. 2009; 30(1-2):87-98.

Savall A, Marcoux P, Charles R, Trombert B, Roche F, Berger M. Sleep quality and sleep disturbances among volunteer and professional French firefighters: FIRESLEEP study. Sleep Med. 2021 Apr; 80:228-235. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.01.041. Epub 2021 Feb 2. PMID: 33610069.

Ramírez-Vélez R, Agredo RA. Fiabilidad y validez del instrumento "Fantástico" para medir el estilo de vida en adultos colombianos [The Fantastic instrument's validity and reliability for measuring Colombian adults' life-style]. Rev Salud Publica (Bogota). 2012 Mar-Apr;14(2):226-37. Spanish. doi: 10.1590/s0124-00642012000200004. PMID: 23250366.

Número de bombeiros. April 14th 2023. 2022. https://www.pordata.pt/portugal/numero+de+bombeiros-1188

Portuguese General Secretariat Ministry of Internal Administration. Mulheres Mai(s). https://www.sg.mai.gov.pt/Documents/MulheresMAI_VF_08_03_2021.pdf

Frattaroli S, Pollack KM, Bailey M, Schafer H, Cheskin LJ, Holtgrave DR. Working inside the firehouse: developing a participant-driven intervention to enhance health-promoting behaviors. Health Promot Pract. 2013 May;14(3):451-8. doi: 10.1177/1524839912461150. Epub 2012 Oct 22. PMID: 23091304.